Sandy Smith visits her son’s grave whenever she is in Hampton. The marker was paid for by fundraisers and donations from people who heard about Stephen’s story. (Photos by Caleb Bozard)

In 2021, Sandy Smith started seeing strange cars in her driveway. People were pounding on her front door at 1 a.m. Her phone started ringing so much she disconnected her voicemail. The constant strangers in the yard were scaring her granddaughter who was living with her.

“I’d hear a noise, peek out the window and there’d be a car in the driveway,” she said. “I’d say, ‘I don’t know who that is. I ain’t going out there.’ (I’d) come home from work, go down the road, there’d be cars in the yard, I’d just keep going.”

Sandy Smith’s son, Stephen, was killed in 2015, six year earlier, in what was ruled a hit-and-run in Hampton County, South Carolina. He was 19, and his body was found three miles from his car, which was out of gas. Though Sandy and her family had questions about Stephen’s death from the beginning, the case ran cold, she said during several interviews with The Carolina News & Reporter about her story.

For years, Sandy and her family tried to get authorities to reopen the investigation, but nothing changed.

Last year, the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division reopened Stephen’s case as part of the investigation into the 2021 killings of Paul Murdaugh and his mother, Maggie. Some media reports said Stephen Smith knew Richard “Buster” Murdaugh, the surviving older Murdaugh son, but SLED and local law enforcement have not confirmed that.

Suddenly, the Smith family and Stephen’s death became part of the ongoing Murdaugh media saga involving financial crimes, drugs, a hitman and five deaths during four incidents spread over six years.

“Most people don’t know Stephen unless you say ‘Murdaugh,’” Sandy Smith said. “And I hate to have to associate my son’s name with them people. That’s really depressing.”

Since Maggie and Paul Murdaugh were killed, Stephen’s – and Sandy’s – story has been featured by CNN, the New York Post, HBO, Dateline, 20/20 and numerous international podcasts. Sandy hasn’t answered Netflix’s calls because they want an exclusive contract. She has received offers for book deals.

“I’m not ready to sit down and talk about no book,” she said. “I don’t even have answers yet. What am I going to talk about? The same stuff? Because that’s the thing with my case. … All I can say is the same stuff over and over and over again.”

SLED’s investigation into Stephen’s death is active, said public information officer Renee Wunderlich.

No arrests have been made in Stephen’s case.

In addition to Stephen’s death and those of Maggie and Paul Murdaugh — the wife and son of lawyer Alex Murdaugh — other incidents under investigation include the 2018 death of Murdaugh housekeeper Gloria Satterfield, the 2019 boating death of Hampton teen Mallory Beach, fraud allegations at Alex Murdaugh’s former law firm, and a drug dealer who was allegedly paid to kill Alex Murdaugh at his own request. The Murdaugh family’s reach is statewide: It has political connections, with members having served as prosecutor in the Lowcountry since the 1920s.

Sandy Smith remembers hearing rumors the Murdaughs were involved in her son’s death immediately after he was killed, but she told people not to believe them. SLED has not released information on why it reopened the case. But it did say at the time that new evidence had been found during the investigation into Maggie’s and Paul Murdaugh’s deaths.

Sandy said the media attention directed toward her and her family has calmed down in the past several months.

“Which is good,” she said. “I can leave my front door open.”

She hopes that now there might be more space to finally find out what happened to her son.

‘EVERYBODY LAUGHED WHEN STEPHEN WAS IN THE ROOM’

Stephen was born premature, Sandy said. He weighed 2 pounds, 12 ounces. His twin sister Stephanie was 2 pounds, 6 ounces.

He loved the water and loved to fish, Sandy said. He was funny. Thanksgiving was his favorite holiday. He liked to read, and his dream was to be a doctor overseas. He was putting himself through college when he died.

“People need to realize they stole that from him. They stole it from us,” she said.

Sandy heard from Stephen and Stephanie that her son was bullied some in high school for being gay, but she said for the most part he ignored it.

“And that’s what I loved about him the most is, you know, you could do whatever, and he’d hold his head up high and keep on going,” she said.

Stephen’s sexuality was never a problem for the family, Sandy said, laughing while recalling a story. Once while Sandy, Stephen and Stephanie were walking back to their car after attending a carnival, a man approached them. The man said someone inside the carnival wanted to chat with Stephen.

“He came back and I said, ‘What was all that about?'” Sandy said. “And (Stephen) said, ‘Well, Mom, if you get a call from a strange number, just don’t answer it … I wanted to give him a working number but not mine, so I gave him yours.'”

Stephen was very close to his sister, and they would sometimes drive to the LGBTQ bars in Columbia and Charleston. He and Sandy would talk about guys he was talking to — without mentioning names.

“He never had to come out” to us, she said. “He always knew we loved him.”

While they think he was killed because he was gay, Sandy and Stephanie think the media focuses too much on his sexuality.

“I want Stephen to be remembered as Stephen and not some gay kid that got beat up because he was gay,” Sandy said. “Because he was a person, no matter what. He always said, ‘God made me, and God don’t make mistakes.’ He said, ‘I am who I am.’ And that’s what he was.”

THE DARK YEARS

Stephen’s body was found on the median line of Sandy Run Road in Hampton early on the morning of July 8, 2015.

S.C. Highway Patrol incident reports from the crime scene list Stephen’s injuries as being blunt force trauma to the head, with no vehicle debris nearby.

From the beginning, Sandy thought he had been beaten, but she still doesn’t know who did it — or why it was ruled an accident.

There wasn’t much news coverage of Stephen’s death in 2015, Stephanie said. The media reports were basic: A 19-year-old man in Hampton had been hit by a car. Sometimes they would mention he was gay.

Stephanie thinks Stephen being gay and not from a family with money made his case seem less important.

“It was kind of like, to a lot of people, Stephen didn’t matter. And it just made it a lot harder than it should have been,” she said.

During the years that the case was quiet, the Smith family walked the miles between where Stephen’s car was found and his body was found — down roads, through woods, corn fields and swamps, trying to find any evidence that could tell them what happened.

One time, she said a state trooper stopped her and asked what she was doing.

“I’m looking for evidence,” she said she replied. “No one else is out here looking for it.”

Sandy said she wrote letters — to the FBI, to the South Carolina governor’s office, to crime television personality Nancy Grace — to try and get someone to look at the case.

But it seemed like no one was listening. Until Mallory Beach died.

THE MEDIA ARRIVES

When Beach, 19, was killed in 2019 during the crash of a boat allegedly driven by Paul Murdaugh, people started asking about Stephen again, Sandy said.

Paul Murdaugh later was indicted in the death and was awaiting trial.

But it wasn’t until Paul and his mother, Maggie, were found dead two years after the crash that the cars starting showing up at Sandy’s house and the knocks on her door began. Stephen’s case was now possibly connected to other deaths involving a prominent Lowcountry family.

One of those door knocks came from Brooke Brunson, a producer with HBO Max’s “Low Country: The Murdaugh Dynasty” series.

Brunson told The Carolina News & Reporter she hadn’t heard about Stephen’s death until she started asking questions about Beech’s death. She spent three hours talking with Sandy off the record that first night. HBO later interviewed Sandy and Stephanie on camera for the project.

“If it had been Paul Murdaugh that had been left in that road, like a piece of trash, you better believe there would have been calls to the governor,” Brunson said. “… There would have not been any option to just let that case fade away.”

Both Sandy and Stephanie said they are happy with how HBO handled their stories. But they can’t say the same for other coverage.

Sandy has stayed in touch with several of the reporters who contacted her, namely Mandy Matney.

Matney helped break the news of the Murdaugh saga through her work with various local outlets and now is self-producing a successful podcast, “The Murdaugh Murders.”

Matney has received criticism for her close relationship with the Smiths, she admits. But she doesn’t think many of the breaks in the Murdaugh story would have come if she wasn’t close to the story.

Like Brunson, Matney thinks the story has gotten heightened media attention because – beyond the salacious details – it is a story of inequality that many in America can relate to.

“It’s really, when it comes down to it, a story about the two systems of justice and how it works one way for people like the Murdaughs and it works another way for people like the Smiths,” Matney said.

Matney said she is inspired by the fact that Sandy has relationships with and supports the other families involved in the Murdaugh cases, including those who have more answers about what happened to their loved ones than she does.

Sandy said the Beaches are “good people.” And Sandy attended the launch ceremony for a charity founded in Gloria Satterfield’s name by her family, Matney said.

“Because this case is so chaotic, and there’s twists and turns every month, there’s never been a point where we can all focus on Stephen,” Matney said. “And I know that that’s hard on her.”

Stephen’s story has resonated with the LGBTQ community, though. His headstone — along with his father’s, who died three months after Stephen — was paid for through fundraisers, including one hosted by The Capital Club in Columbia. Organizers at the fundraiser, called #standingforStephenSmith, said they started a GoFundMe page for a new headstone after seeing a Facebook post about his grave lacking one.

At the unveiling of the headstone on July 17, 2022, several LGBTQ people said Stephen had made them more brave in coming out, said Sandy’s lawyer, Mike Hemlepp. Some came from other states, including media from HBO and other outlets.

“When young people are afraid of coming out, one of their biggest things that they’re afraid of is violence. …. They’re afraid of exactly what happened to Stephen,” said Hemlepp, who is gay. “There are 23,000 (young LGBTQ) people in South Carolina who know exactly what happened and exactly why. And that resonates.”

Members of the community approach Sandy often and give her hugs or words of encouragement, she said.

Sandy now works as a cook at a private school in Blackville. Recently, a young student recognized Sandy from one of the programs about her story.

“She said, ‘I seen you on TV. (You were) in a movie. … It was very sad,'” Sandy said. “I said, ‘Yeah, it is a sad story.’”

‘JUST A MATTER OF TIME’

Sandy has been contacted by other families in similar situations. She gives them advice on how to file Freedom of Information Act requests. FOIA requests are used by the public — citizens and journalists alike — to gain access to government records. Sandy said she has filed many of them.

She’s glad people are talking about Stephen more than they were in 2015, but she wishes it didn’t have to take more deaths for it to happen.

At first, Sandy said, she felt like the other families were getting answers that she had been waiting for. But then, she realized that it took years for those families to get answers, too.

“That just makes me fight harder, because there’s an answer in that future,” she said. “Just like they got their answers, I’m going get mine. (I) can’t be jealous.”

She said she wants justice for everyone.

And she hopes now that some of the media circus has calmed down, law enforcement will give more attention to Stephen’s case.

“I’m waiting till that day when it’s just Stephen’s story,” she said.

The age of the case isn’t a good sign for SLED, Hemlepp said, noting it’s the oldest of the Murdaugh cases. But he is encouraged because Hampton is a small community.

“People know,” he said. “They know what happened. It’s just a matter of time.”

‘THAT’S WHAT MOTHERS DO FOR THEIR CHILDREN’

When she’s not being interviewed about her son’s death, Sandy tries to keep busy — cooking, watching movies and spending time with her grandchildren.

It’s hard to repeatedly talk about what happened to Stephen. Stephanie said she has her own story pretty much memorized at this point.

“(People) don’t know how I do what I do,” Sandy said. “I say ‘because I’m fighting for Stephen.’ That’s why I do it. That’s what keeps me going. That’s what mothers do for their children.”

Stephanie and Sandy have gotten closer since Stephen and the twins’ father died. They talk on the phone every day.

“I couldn’t imagine losing my child,” Stephanie said, referring to her own daughter. “My mom had Stephen for 19 years. That’s 19 years — that’s it. You know, I’m about to be 27. I’m still here, but Stephen is not. … I couldn’t imagine what my mom’s going through. And I don’t want to imagine it.”

Stephen’s grave is located at Gooding Cemetery in Hampton, just down the road from where his body was found and a 45-minute drive from Sandy’s home.

Sandy said it’s still hard to visit. She mainly goes there when she’s in town to see her grandchildren. Stephen liked cats, so she leaves little ceramic ones on the headstone.

“He would be amazed (at the support),” she said. “And the first thing he would say – like if he seen his headstone – he’d say, ‘Did you do that for me?’ That’s just the type of person he was. He was never expecting anything. … Yeah, he was a good kid.”

Stephen Smith was found dead on a roadway in 2015. His death was ruled a hit-and-run, and eventually the case went cold. But it was reopened in 2021 as part of the investigations into the killings of Maggie and Paul Murdaugh.

The spot where Stephen’s body was found on Sandy Run Road in Hampton County is marked by a cross.

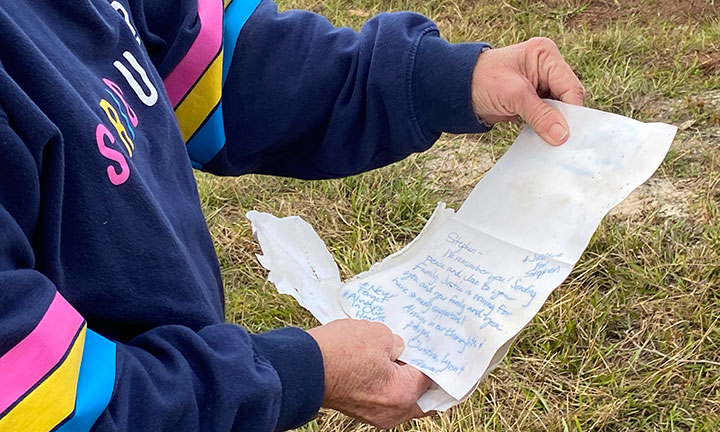

Sandy Smith often receives cards and online messages from people who have heard Stephen’s story. This note she found Nov. 19 was the first she had seen at the marker where his body was found.

Sandy Smith kept this canvas depicting her and Stephen after it was used during a CNN roundtable discussion with the other families of victims associated with the Murdaugh investigations.

Sandy tries to keep busy to keep her spirits up. She likes to cook and sometimes feels Stephen’s hand on her shoulder while she’s at the stove.

This painting of Stephen was given to Sandy at a fundraiser held at Columbia’s Capital Club in Oct. 2021.