Members of USC’s Black fraternities and sororities, such as the ladies of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, stroll to hip-hop music during a recent Hip-Hop Wednesday. (Photos and graphic by Jayden Simmons)

Over the past decade, hip-hop has grown in popularity and is now one of the most listened-to music genres in the United States.

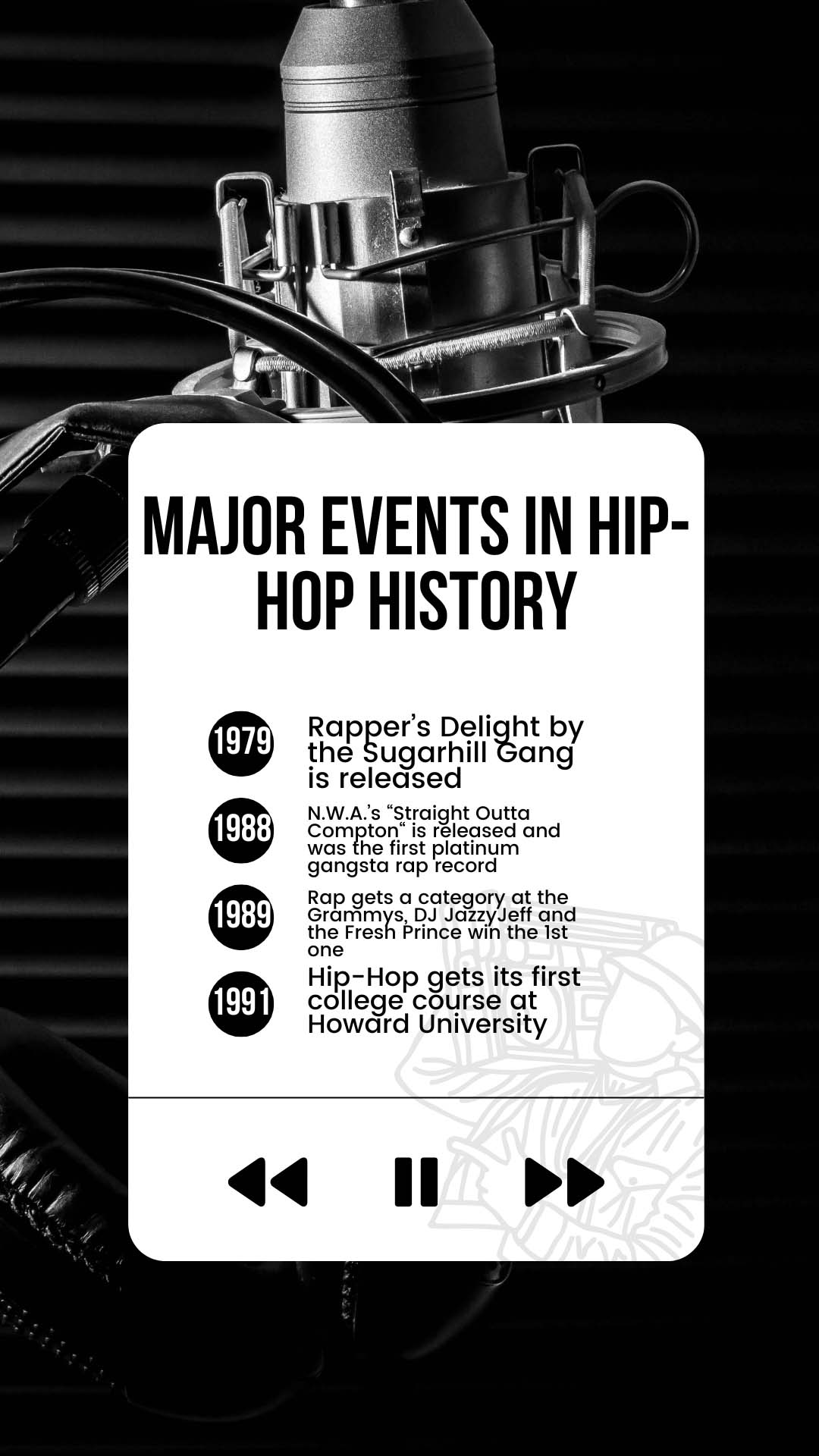

Hip-hop has evolved from not being recognized at the GrammyAwards 35 years ago to being part of college curriculum today.

It’s important that the history of hip-hop be taught in college classes because its roots go hand-in-hand with American media history, said Jabari Evans of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of South Carolina. There have been several USC courses dedicated to the genre. This year, Evans even introduced a hip-hop media and society course.

He said he pitched the idea of the hip-hop class, and USC adopted it this semester.

“When I first pitched it, it was going to be a smaller course, but now it’s being added to our curriculum,” Evans said. “It’s going to be something that I teach more regularly. And it’s got its own course number now.”

ORIGINS OF HIP-HOP

Hip-hop originally included five elements: emceeing (rapping), DJing, break dancing, urban graffiti and beatboxing.

Evans said the hip-hop genre was created by Sylvia Robinson, an R&B singer who observed break dancers and “break beats” made from disco records.

She produced the first-ever hip-hop track, “Rapper’s Delight” by the Sugarhill Gang, which sampled the funk song “Good Times” by Chic.

“Rapper’s Delight” was certified gold, meaning 500,000 copies were sold, then later went platinum.

College students at the time, in 1979, took to the new genre immediately.

Brooklyn native Kevin Simmons was entering college in Long Island at the time. While on campus, he and his friends joined student organizations that advocated for bringing rap artists to the school to perform for the student body.

“There was something for everyone,” Simmons said. “No matter what you choose to do, there was a genre of hip-hop music that could be considered the soundtrack to your life.”

Simmons and others took part in performances with major rap artists while in college.

“I remember going to the dance studio at night with my friends and rehearsing dances just to do at parties,” Simmons said. “Some of my friends actually got the chance to dance for rap artists like Kool Moe Dee, Big Daddy Kane, and EPMD and tour the country.”

Evans said each element of hip-hop served as a medium for communication and public discourse in the Black community. Yet it was largely considered a public nuisance when it initially hit the airwaves.

“So graffiti? Violating public space,” Evans said. “Breakdancing? Why are these young people panhandling? And older teens were doing that at playgrounds and park areas that were for young children. So people complained about hip-hop — hip-hop was a nuisance. It was something that took up public space.”

Evans said some media stories associated many aspects of hip-hop with deviancy. However, the creators of the music used it as a means of telling their stories.

THE INTRODUCTION OF GANGSTA RAP

Mainstream hip-hop saw an evolution in the late ’80s inspired by a group from Compton, California, known as N.W.A.

Made up of Dr. Dre, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, DJ Yella and MC Ren, the group pioneered a new style of rap called gangsta rap, which contained heavily explicit lyrics that reflected street gangs, violence and other elements of the day-to-day scene in rough, inner-city neighborhoods.

Evans said hip-hop in the mass media’s eye, however, became less about speaking out against oppression and more of a spectacle about a party lifestyle, making money, and selling drugs.

“Really the tipping point is N.W.A., who goes platinum,” said Evans. “The music industry really is like, ‘OK, this rap distraction is real.’ That’s 1988 with (the album) Straight Outta Compton. So when that comes out, it just so happens that that’s the brand of hip-hop corporate record labels buy into as the formula to sell rap.”

One highly controversial song on the 1988 disc was “F*** Tha Police,” which contained lyrics that protested police brutality and racial profiling.

The song’s popularity provoked the FBI to write to the record label disapproving of the song. Atron Gregory, N.W.A.’s tour manager, told GQ magazine in 2020 that police officers in Detroit stormed the stage while the group performed the song in 1989, causing the rappers to run off the stage.

The song became a rallying cry a few years later during the Los Angeles riots following the police beating of motorist Rodney King.

Some media personalities labeled the group’s music as hate speech, and the group was banned from several radio stations.

“It becomes real problematic,” Evans said. “Stereotypes about Black men are heavily influenced by hip-hop and actually gives hip-hop, and gangsta rap in particular, more PR and advertising than ever. And it really just influences this to be the formula from now on, like, even up until today. The hustler, the gangster, you know, there’s an image of Black masculinity that dominates commercial hip hop, from that point on.”

N.W.A. inspired more West Coast artists’ rise to prominence, such as Ice-T, Too Short and Cypress Hill — each of whom capitalized on the new sound in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

“It had a completely different vibe, with thunderous bass and melodic sound,” Simmons said. “This era in hip-hop music was the best era to me because it was so diverse and multi-dimensional, all within one culture.”

East Coast street rap became prevalent shortly after, with artists such as Eric B & Rakim, Nas, Mobb Deep and Wu-Tang Clan gaining the attention of New Yorkers.

“Although we were in college, a lot of us could relate because we came from that environment,” Simmons said. “A lot of kids that I grew up with didn’t get that chance (to go to college), which made the music more relevant in who we were and what we were going to become.”

HIP-HOP HITS THE CLASSROOM

Howard University was the first college to offer a hip-hop-specific class, in 1991.

Evans said the idea of hip-hop in academia has shifted from professors being interested in the genre to having in-depth conversations about what makes hip-hop not just a genre, but a culture.

“We’re talking about hip-hop — not only as an artistic practice — but we’re talking about experiences in hip-hop,” Evans said. “We’re talking about how hip-hop shapes and shifts public discourse, how it speaks for those who are marginalized and how it contributes to their sense of belonging in America.”

Tre Harris, a senior at USC, took one of these courses last semester, the Cultural History of Hip-Hop Music, taught in the African-American Studies Department.

“That (class) allowed me to write my final paper about gangsta rap and how that fits into the African-American story,” Harris said. “It allowed me to connect with hip-hop more.”

Chuck D from the rap group Public Enemy described hip-hop as “CNN for black people” in 1993, and Evans said instructors serve a similar purpose by teaching about the history.

“I think that there’s an understanding there where, if we’re going to talk about Black culture in any facet of academia, then there’s going to be a level of hip-hop within it,” Evans said. “That used to be a controversial thing to say in like the ’80s, and ’90s. But now, it’s not even controversial to say that hip-hop belongs (as you) talk about Black life.”

Outside of the classroom, hip-hop culture is a fixture on campus the first Wednesday of each month with “Hip Hop Wednesday,” put on by the Office of Multicultural Student Affairs.

A DJ plays music in front of the student union as students mingle with multicultural student organizations as well as Black fraternities and sororities, typically referred to as the “Divine Nine.”

Evans is a member of Divine Nine fraternity Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity. He said hip-hop culture is just as important to these organizations as it is in a classroom setting.

“Hip-hop is civic engagement. Greek life is civic engagement,” Evans said. “And at a college level, it becomes another community that you’re a part of. The performative aspect of hip-hop is always going to be there, because hip-hop is a Black culture.”

The Divine Nine organizations each have their own steps and strolls — an organized dance that represents unity and power — typically set to hip-hop music.

“Certain songs are associated with certain organizations,” Evans said. “It was dialogue. It was discourse happening through performance, the body. We’re actually speaking to each other (through) song. So that’s another reason why Greek Life was very much hip-hop.”

Harris is a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity at USC and a regular at Hip Hop Wednesday.

“We stroll to hip-hop songs all the time,” Harris said. “It’s the default genre we use to express ourselves in that way because hip-hop is so Black.”

The evolution of hip-hop in the college realm has reached a point many professors never thought it would.

“The fact that I can teach a class, that’s not in African American Studies, that’s about hip-hop, that’s big,” Evans said. “You could have a hip-hop class now in political science, you could have one in sociology, you could have one in anthropology. It doesn’t need to be limited to being seen as a part of Black studies. You can be getting an MBA at Darla Moore, and it could be talking about hip hop and entrepreneurship class. So it’s taken so many different shapes and forms.”

For Evans, the ultimate goal is to teach the importance of hip-hop at its roots, so students can understand why it continues to serve as a voice for the voiceless to this day.

“Hip-hop always moves forward. It respects the past, but it doesn’t live in the past.”