A viewing room for caskets that families can pick from for their deceased loved one (Photos by Bridget Frame)

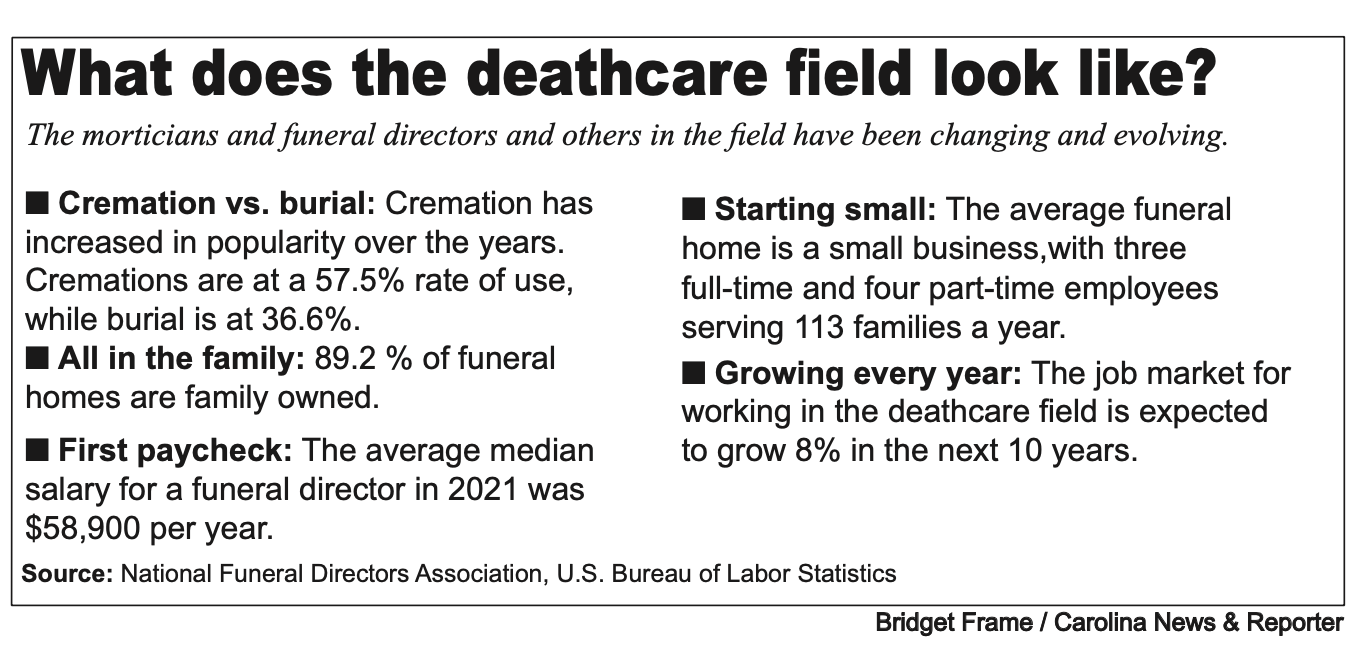

The deathcare industry, which involves the work of funeral directors and morticians, is facing a shortage that puts a crucial field at risk.

More than 60% of funeral home directors are expected to retire within the next five years, according to the National Funeral Directors Association.

That, along with the intense stress put on the industry by COVID, the profession’s long, unpredictable hours and the emotional demands of the job are all contributing to the problem.

“There is a severe shortage of funeral directors right now in the country,” said Gregg Turner, funeral director for Thompson Funeral Homes in Columbia and Lexington.

And there is no quick fix.

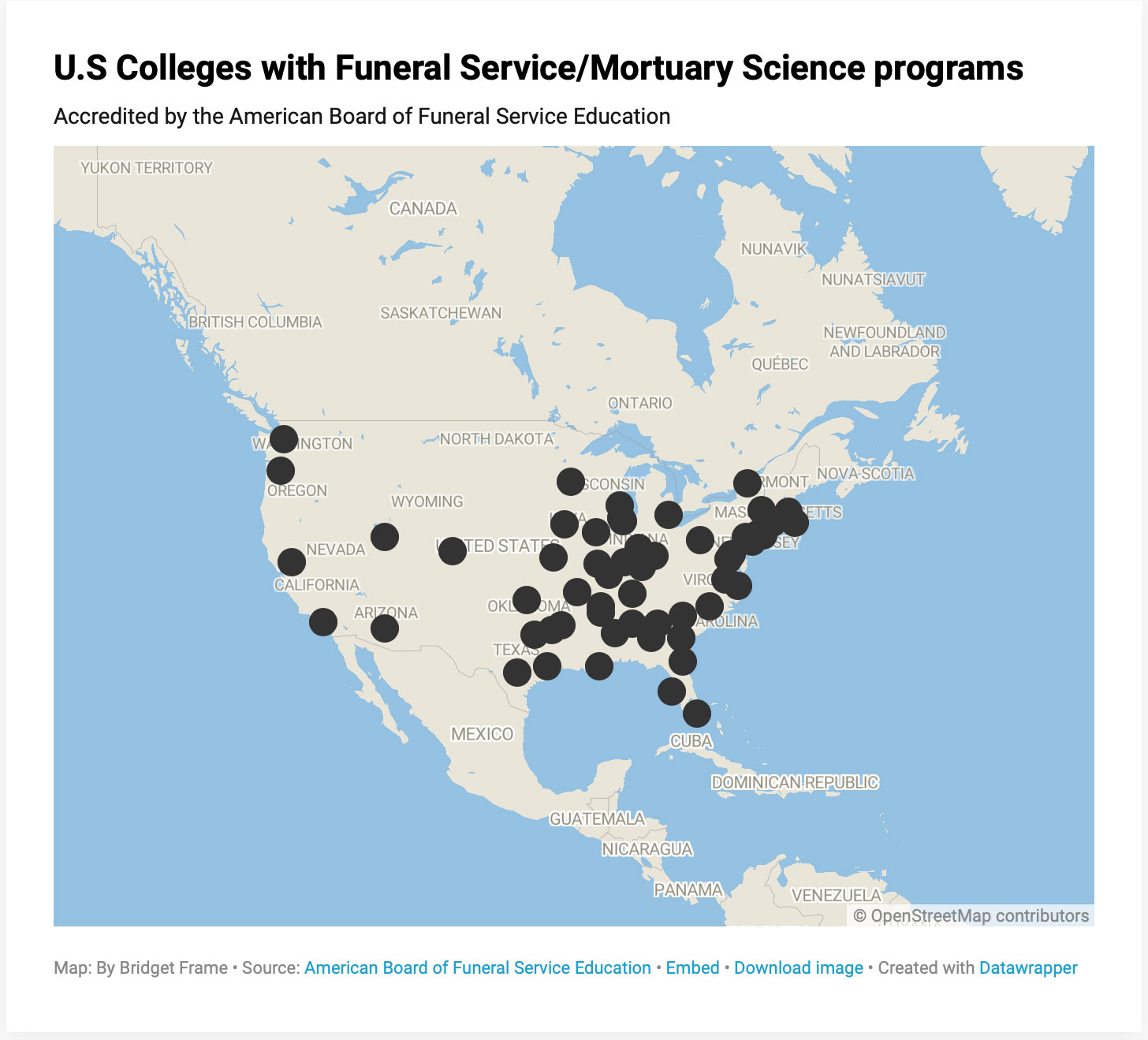

Enrollment in mortuary science education has increased. But because of the volume of people leaving the field, and the length of time it takes to become a licensed funeral director, there is an employment gap that leaves the trade lacking. There are 58 U.S. colleges with accredited funeral director/mortuary sciences degree programs.

Becoming a licensed funeral director in South Carolina is a multi-year process.

First, the student attends a mortuary school or technical college that has a mortuary degree program. This two-year degree teaches the student to learn skills such as embalming.

The next step is having an apprenticeship with a funeral home. That can last up to two years.

The student then must pass a board exam and a legal exam to receive a license.

Turner said that while many funeral homes have raised salaries to encourage people to join the trade or join their staff from other funeral homes, jobs still stay open. He has seen positions go unfilled for up to nine months.

A calling to serve

Those who choose to work in the field are impassioned about what they do.

Working in funeral services is a career that takes heart. Some say they were called to the role of funeral director.

A.A. Dicks Sr. began his career in funeral service at 14 after a relative passed away and he saw the comfort the funeral director gave to his family during their grieving.

“The mannerisms and the way in which our family funeral director talked to and with my grandmother just inspired me. I wanted to be like him,” Dicks said.

Dicks volunteered at the funeral home through the Neighborhood Youth Corp at age 16 and later attended Benedict College and Gupton-Jones College of Funeral Service.

In 2000, after working for Palmer Memorial Chapel as a funeral director for years, he opened his own funeral home, A.A. Dicks Funeral Home in Columbia.

Preparing the body is one part of the process, but assisting the grieving family is a major component of the job.

“You’re dealing with people’s worst days of their life, so you have to be ‘on’ all the time,” said Scott Pomeroy, a fifth-generation funeral director at Pomeroy Funeral Homes in Michigan.

“Sometimes … that can be really hard, especially if it’s a young person’s death or something very tragic,” Pomeroy said. “… You have to do your best to be the strong person in the room.”

Burnout is real

Kara Norris, a former funeral director and mortician in Florida, knows how difficult the job can be.

She now works as a bereavement specialist and does grief counseling for a hospice organization.

“When I was in the funeral business, my schedule was like nine days on and one day off (or) five days on, and you get two days off,” Norris said. “So it’s not an easy schedule, especially if you have a family and kids. It’s not always a job where you’re going to get out at 4 or 5.”

The burnout experienced by funeral directors increased exponentially during COVID, which increased the work of deathcare workers and often kept families away from their loved ones’ bodies.

“I think COVID really did a number on people,” Norris said. “The hardest part for me during COVID … was sitting with families and not being able to say, ‘You can see them again,’ or, ”You can have the funeral you wanted.’ That was just heartbreaking.”

The future of funeral services

So, what does the future look like for the deathcare field?

There are new challenges with the employee shortage, in part because many people preparing for the field are still in school. But there are some other new factors that will expand the industry.

Women now make up the majority of mortuary students, so opportunities are opening in a male-dominated field.

There also are changes in how bodies are being prepared after death. Cremation has become a more popular form of burial.

And there are more environmentally friendly options to return the body to the earth or preserve the memory of a loved one.

Urns can be put into the soil to grow a memorial tree are increasing in popularity. And bodies can be buried straight into the earth, without a coffin, at special cemeteries.

But many in the business say the new practices create more opportunities for the industry to grow – but also, again, to support people during their bereavement.

“They think that the funeral business is just so morbid because … they don’t really understand that it’s really about the living,” Dicks said.

Thompson Funeral Home’s Lexington location contains a chapel, a viewing room and a preparation room.

The hearse is used in a funeral procession to carry the casket and the deceased to the funeral home.

This gathering room is used for families and friends of the deceased to meet with visitors.

The deathcare field now has a higher rate of female employment.

This map of mortuary science programs is interactive. You can see it here.