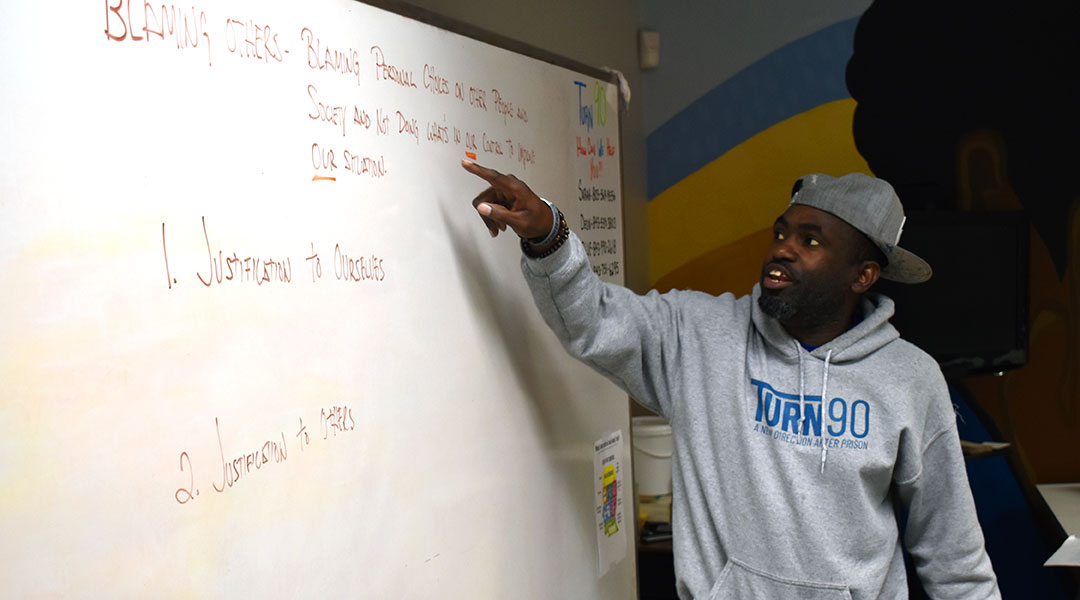

Deon Nowell leads a skills lesson at Turn90’s Columbia print shop. Nowell, a Turn90 graduate, said he told Turn90 founder Amy Barch during his time in the program that he would be working for her one day. (Photos by Wade Rainey)

In 2004, Deon Nowell was federally indicted and sentenced to 25 years in prison on gun and drug charges.

Ten years later, Nowell worked with his lawyers three different times to petition for clemency after the Obama administration announced a clemency initiative. That initiative allowed certain inmates to petition for early release or a reduction in their sentences.

Nowell was denied all three times.

In 2016, he decided to try again and write a letter on his own behalf. He was granted clemency the next year.

Then, while living in a halfway house, Nowell discovered Turn90, a re-entry program for recently released inmates.

Turn90 program founder Amy Barch visited one day and met Nowell. He was on board.

He trained and he worked for couple of years in other jobs. Then Turn90 offered him a job as a classroom facilitator in the very program that gave him his leg up.

“I feel like this is something I’m born to do,” Nowell said.

Second chances

In the United States, convicted felons lose much more than their freedom.

Although details vary from state to state, those convicted of a felony can expect to lose their right to vote, their right to bear arms and, for some, their ability to take out a federal loan.

One of the biggest barriers for success after prison for many, though, is finding a job. Background checks often immediately eliminate many formerly incarcerated people from an applicant pool, regardless of merit.

A recent Prison Policy Initiative study showed the unemployment rate for the formerly incarcerated is 27%, nearly five times higher than the rate for the rest of America.

Programs such as Goodwill’s Pathway Home and Turn90 are trying to give the people behind that percentage a solid second chance.

“For anybody, male or female, to come out of a correctional setting …, it’s tough,” Turn90 Director of Programs Lisa Davis said. “There are automatic barriers.”

While Turn90 and Pathway Home have similar goals, each organization operates differently.

A pathway home

Pathway Home is funded mainly through a grant from the Department of Labor. Eligible participants need to meet certain criteria such as returning to live in designated areas once they’re released.

For the Upstate and the Midlands of South Carolina, eligible returning citizens must reside in one of eight counties: Anderson, Greenville, Greenwood, Oconee, Pickens, Richland or Spartanburg.

But how do people find out about Pathway Home?

Vincent Reidy, the program’s mission manager, credits the relationship Pathway Home has with the S.C. Department of Corrections for bringing interested and eligible people to their attention.

“Without them, this doesn’t happen,” Reidy said. “It’s all about our relationship with them because … our career navigators go into the prisons to do classes to meet with individuals.”

“They’re (the Department of Corrections) actually our voice inside the facility,” he said.

Pathway Home works with six state correctional facilities. They are in the process of adding a seventh, Reidy said.

The program works by reaching out to specially identified and cleared inmates within 72 hours of their release. Then the work begins.

“We meet with them in person and see what they’re interested in,” Reidy said. “A majority of the folks that go through our program, we help them get employment and in a field that they desire, especially if we can help pay for their training.”

The program partners with Greenville Technical College, Midlands Technical College, Commercial Driving Academy and others to provide instruction and certification for a commercial driver’s license, HVAC, welding and other fields.

Challenges still exist for Reidy and the rest of his team, and the participants, too.

“The biggest barriers are transportation and housing,” Reidy said. “Communication is a big deal, too. Folks don’t have phones. It’s hard for them to even call their probation officer or a career navigator.”

For Reidy, overcoming those issues with participants is more than worth it.

“I got a text about 15 minutes ago that one of our participants in Spartanburg passed a CDL (commercial driver’s license) qualification,” he said. “So now he’s going to be able to provide for his family and his kids and break that cycle.”

“The stories are the most rewarding when people simply say, ‘Thank you,’” Reidy said. “That sounds kind of corny, but that’s what it’s about.”

Turning in a new direction

Turn90 is much more self-contained than Pathway Home, featuring in-house classes, support services, employment and, eventually, job placement.

Amy Barch founded the organization in Charleston in 2011 under the name Turning Leaf. It originally served as a jail-based program and an alternative to prison by providing behavioral classes and helping to secure post-release transportation, housing and employment.

In 2016, Turning Leaf shifted gears, becoming a reentry program, focusing on community-based reentry services. In 2017, Turning Leaf opened up its first T-shirt print shop in Charleston, where participants could work part time.

Turning Leaf rebranded in 2021, changing its name to Turn90, and opened a second print shop in Columbia.

One unique aspect of Turn90 is the hiring of program graduates.

In 2022, Terrence Ferrell became the first program graduate to hold a senior leadership role at Turn90 when he was promoted to director of production from his role as Columbia Print Shop manager.

Others, like Aulzue “Blue” Fields and Deon Nowell, serve as peer specialists and classroom facilitators.

For Fields, his work as a peer specialist allows him to use his own experience in prison to relate to members of the program.

“(I’m) able to explain to the guys, it can be done, but it’s a battle,” Fields said. “It’s just me constantly looking in different areas to help, but also deal with the guys on the one-on-ones to figure out what they’ve got going on.”

It’s not just the content and activities that help the members of the program succeed.

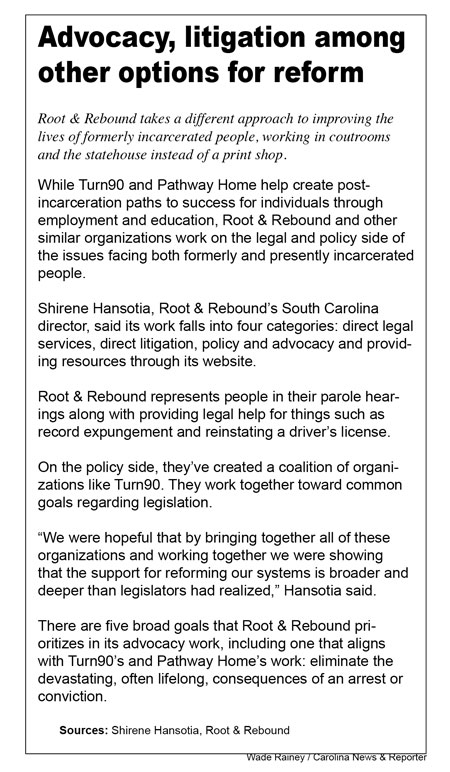

“It’s a safe, positive environment because they can be themselves,” Fields said. “They can allow their defense(s) to come down to a degree and not be as defensive because of the trauma experienced in the incarceration community. And then they take this and they begin to practice it. And their family and loved ones are able to see the new person.”

Nowell uses the lessons he learned during his time in Turn90 to shine in his role as a classroom facilitator, leading sessions based around Turn90’s skills curriculum.

Turn90 teaches 25 essential skills in behavioral classes. They are broken into three categories: general skills, emotional regulation skills and workplace skills.

Nowell said that when he was with the program, sessions that taught him how to stop and think through an action were the most helpful.

“I’m not just saying, ‘No.’ I’m not just trying to be honest. I’m not just talking about my feelings,” he said. “I have to brainstorm and think about my feelings. I have to brainstorm and think about why I’m saying no, or why I’m even deciding to be responsible.”

Nowell drives more than 90 minutes from Summerville to Columbia for work each day. But he said he doesn’t mind the commute.

“I enjoy it. I truly do,” he said. “This right here gives me the opportunity to actually be giving back and helping myself in the process.”

Working with Corrections

Like Pathway Home, Turn90 maintains a working relationship with the Department of Corrections.

Jake Gadsden, deputy director of Programs, Reentry and Rehabilitative Services for the department, said that in addition to providing a list of those eligible for the program, his office works closely with Turn90 in other ways.

“We’ve asked them to partner with us in one of our major reentry units, Manning Correctional Center,” Gadsden said. “… We have them come in and do a specific class called Thinking for a Change, which is a nationally recognized, evidence-based program.”

Thinking for a Change is a class that works on many of the same skills that Turn90 teaches.

Turn90 staff is also assisting the corrections department with the creation of a new concept that uses “vignettes” to help inmates at the end of their sentences adjust to changes they will face in the outside world.

“We actually sat down with (Fields), who gave an interview and explained just how terrifying it is,” Gadsden said. “When you first walk out and you go to a self-checkout aisle at Walmart or a grocery store, … that didn’t exist when they came in.”

Work like this is being recognized for the service it provides to the formerly incarcerated.

After Turn90’s successful Columbia expansion, the organization set its sights on a third location in the Upstate.

In October, Turn90 received $667,000 from the state to help facilitate that expansion and to continue their work in Charleston and Columbia.

Lisa Davis, Turn90’s director of programs, works at her desk in the print shop. Hired a little more than two months ago, Davis is a new to the Turn90 team.

Nowell facilitates a discussion, while other members of the program study a worksheet. Lisa Davis described the classes as a “free environment” that allows program members are encouraged to speak their minds.

Aulzue “Blue” Fields watches as a member of the Turn90 program presses ink onto a shirt. Fields was the first program graduate to be hired by Turn90.

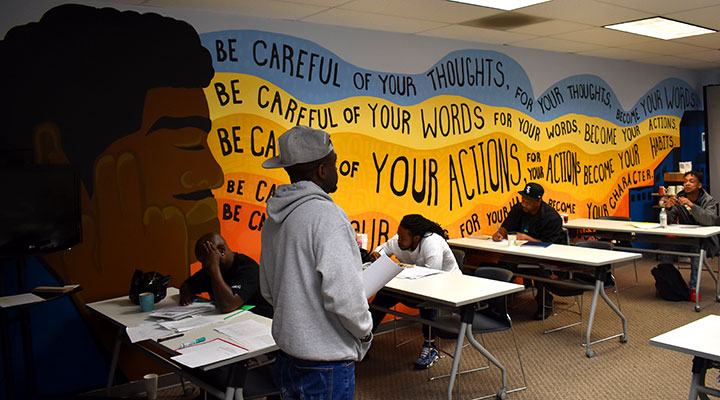

The tag that Turn90 presses into its clothing. The print shops, located in Columbia and Charleston, provide work experience to Turn90 members before they receive job placement assistance.