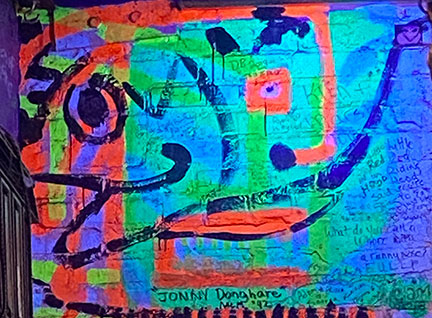

Valerie Fort introduces readers on stage at the Free to Read Fest on Sept. 29. (Photos by Micheal Jacobs III/Carolina News & Reporter)

Evelyn Berry said banning books restricts the individuality of a reader.

“I think it’s important to remember that every book is for somebody,” Berry said.

Berry participated in Sunday’s inaugural Free to Read Fest at Columbia’s Art Bar, created to celebrate Banned Books Week and raise awareness for literature censorship.

The event was organized by University of South Carolina instructor and former librarian Valerie Fort.

Poets, bands and a DJ drove the event. There were also tents outside the bar showcasing organizations that promote the free access of the written word. The proceeds from the $5 cover fee went to the LeRoy C. Merrit Humanitarian Fund, which advocates for librarians and intellectual freedom.

State regulation 43-170 passed earlier this year. The regulation gave the South Carolina Board of Education, not local school boards, the power to restrict reading material in public schools if something is deemed not “age and developmentally appropriate.”

“There might be books you read that shock you or offend you,” Berry said. “They might not be your cup of tea. But for other people, they can be massively affirming and instructive.”

The regulation also allows the parent or legal guardian of any student to file a complaint with their district school board about any book or material they feel should be removed from the curriculum. Fort feels that infringes on the rights of parents who don’t share the opinions of those making complaints.

“If one parent is saying that a particular book is not OK for their child, that’s OK,” Fort said. “They completely have the right to that. But they do not have the right to say it’s not OK for my child, right?”

Another idea the festival was meant to convey was fostering empathy through literature. Because books can be used to reflect the experiences of others, Fort thinks books can help readers feel more understood in their experiences and better understand those of others.

“I think that’s why I think it’s important for everyone to have something out there that they can see themselves in, and they can see what other people are like and what their lived experiences are,” Fort said. “That’s how we can kind of just be more kind to each other, experience joy together and be better humans together.”

Another way the festival promoted access to the written word was highlighting local bookstores. All Good Books, Liberation is Lit and Queer Haven Books all had tents where festival goers could purchase books. Some of the poetry readings were from poets whose works have been banned.