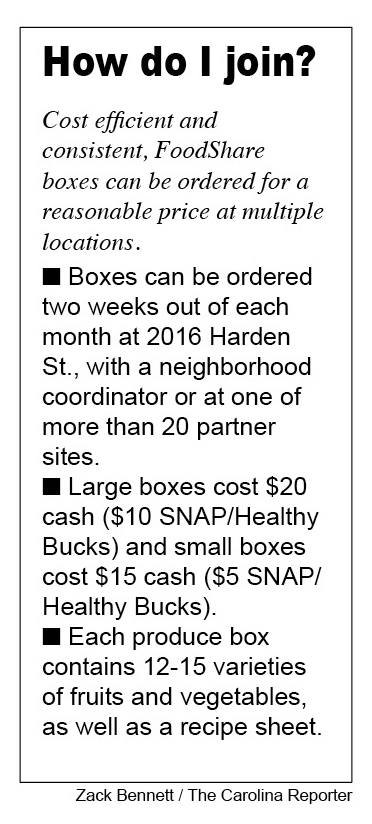

The fresh food boxes are filled with up to 15 varieties of fresh fruits and vegetables, as well as a recipe sheet for that week’s contents.

Customers of FoodShare South Carolina are treated more like family friends than customers as they gather every other Wednesday in a renovated Northeast Columbia store to pick up fresh fruits and vegetables that are scarce at their neighborhood grocer.

Community and conversation envelop the room as volunteers greet people by name and share ways to cook even the most despised of vegetables.

On a recent Wednesday, the nonprofit FoodShare added Brussels sprouts to the Fresh Food Box for the first time, which even dedicated foodies sometimes have trouble swallowing.

As a mother and son approached the check-in table, Cheryle Simmons, FoodShare’s relationship cultivator and FoodShare Hub manager, told them about the new addition to the boxes.

“What? You don’t like Brussels sprouts?” exclaimed Simmons as she waved for them to follow her over to the kitchen. She was prepared for the doubters.

Nearby, a Crock-Pot simmered with oven-roasted Brussels sprouts she made with the sole intention of showing customers just how good they can be.

“We’re not just about food,” said Beverly Wilson, the co-founder and executive director of FoodShare. Wilson, who works in the USC School of Medicine, has come to understand that access to healthy food is critical to defeating heart disease and diabetes that plague low-income South Carolinians. “Health equity: what does a neighborhood, especially the North Main area, need in order to achieve good health?”

Jim LoCicero, a FoodShare volunteer and Army veteran with a degree in horticulture, has spent a copule years growing with the nonprofit.

“It’s opened my eyes in spite of the fact I’ve been doing some of this for forty-plus years – I think it’s a plus for the community,” he said. “I really get more out of it than I give, I believe.”

Wilson and co-founder Carrie Draper created FoodShare in 2015 because they saw that low income families, particularly in North Columbia, too often had to rely on canned goods and convenience store food to live. Since then, the nonprofit has distributed over 585,000 pounds of produce grown mainly by South Carolina farmers, and taught people how to cook what’s in the boxes through its Culinary Medicine classes.

A grant from the Central Carolina Community Foundation provided funds for FoodShare to renovate space in the Save-A-Lot grocery store on Harden Street. In what used to be a bakery and deli section, there is a 20-station commercial kitchen where families enroll in 8-week culinary medicine cooking courses to learn how to cook foods without layering them with heavy oils, butter and salt.

“We [Columbia] just have a lot of low paying jobs, and when you think about minimum wage, there’s just so many studies that support the fact that it’s just impossible for people to have, again, all their basic needs met with that kind of pay,” said Draper, a research associate at the University of South Carolina’s Arnold School of Public Health and vice-chair of the city of Columbia’s Food Policy Committee.

Resolving Health Inequities

Low-income families in North Columbia face a tsunami of challenges, from limited housing to poor schools, abysmal graduation rates and low-paying jobs. Since FoodShare began working in the 29203 and 29204 zip codes in 2015, grocery stores in those areas have all but disappeared as well. That meant residents without cars had fewer food options.

“The Piggly Wiggly on Beltline went out of business, and the Harvey’s on North Main went out of business,” said Wilson.

“Families in Columbia who lack transportation, they have to go to whatever food store is closest to them, and a lot of times that’s a convenience store. So, in order to achieve good health, you have to have reliable transportation, in order to have reliable transportation you have to be able to afford it,” said Wilson.

In total, more than 27,000 Fresh Food Boxes have been distributed to date, which equals nearly 585,000 pounds of produce. Of those boxes, more than 54 percent have been purchased using the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

In addition to accepting payment through SNAP cards, FoodShare is a member of the “Healthy Bucks” program through the S.C. Department of Social Services. When a customer purchases at least $5 of goods from a participating vendor with a SNAP card, they also receive $10 towards fresh produce.

This means a large Fresh Food Box which usually costs $20 becomes $10 for those purchasing with a SNAP card, and a small box becomes $5 instead of $15.

But even if a resident lives within walking distance to a grocery store, it’s possible that the available stock is lacking in quality compared to the same store across town.

Through her research, Draper has been involved in studies that gave her the opportunity to speak about the issues directly with locals. There are, she said “a lot of stories about frustrations with the quality of, especially fresh foods and fresh produce and meat, and how you can go to one store off North Main that’s the same grocery store as in the Shandon neighborhood, but the quality and availability of foods look quite different.”

Car breakdowns, job loss and lack of funds often hinder those who want to improve their diets.

The Central Midlands Regional Transit Authority bus system (The COMET) is the first option of many who do not own a reliable mode of transportation.

While this does offer a solution, it is not a cheap one if this is the only reliable form of transportation available to them.

FoodShare noticed and did something about it.

“For participants who need bus passes to come pick up their box, we are also able to give them bus passes. If you can catch a bus, we’ll give you a bus pass to come back for your next trip. We do try to address those transportation issues by looking at different options, like the NeighborShare program or the bus tickets,” said Wilson.

To more directly combat the lack of transportation, FoodShare created NeighborShare, a volunteer program to allow those with the necessary resources to help those without. NeighborShare has two levels of involvement: helping place orders and helping with delivery.

“We have a number of people that live in Cayce and they want to participate, but they have zero transportation, and they’re housebound, so we need people that would be willing to come to the FoodShare Hub and deliver it, almost like Meals on Wheels. Basically, take responsibility for delivering that box and be pretty reliable. That’s a program that we really want to grow,” said Wilson.

Food as Medicine

Painted in huge letters above the kitchen inside the FoodShare Hub is a quote from the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates: “Let food be thy medicine.”

In that spirit, FoodShare offers Culinary Medicine classes. One component of the program involves classes teaching participants how to create healthy meals at home.

“We really stress working with patients with diabetes and those with high blood pressure, and they come in and they do about a three-hour class,” said Wilson. “It’s hands on, and it’s learning how to control chronic disease using plant-based foods.”

LoCicero said the customers seem to be enthusiastic about it.

“They’re getting imparted with the nutritional value of fresh produce. It affects their lives and their health, and that of their children and families,” he said. “They’re teaching cooking courses so those folks that aren’t familiar with some of the approaches to cooking nutritious meals are getting it here for no charge.”

The second component involves classes of medical students from USC.

“What we’re doing is, students that are enrolled in the med school can participate in those classes, and we teach students how to work with their patients that are struggling with chronic disease,” said Wilson.

The impact of these initiatives is clear to see inside FoodShare’s Hub at the Save-A-Lot.

Walking into the Hub, surrounded by warm smiles and conversation, customers understand FoodShare is about more than just food. Staff and volunteers believe food is medicine for everyone, not just those that can afford it.

Gordon Schell, left, FoodShares’s director of operations, and volunteers prepare for customers at the pick up station where they receive their fresh food boxes.

Michelle Troup, FoodShare’s director of culinary medicine, begins to prepare some cauliflower for the day’s healthy lunch in the kitchen of FoodShare’s Hub on Harden Street during pickup on a Wednesday.

The community board at FoodShare’s Hub includes photos of customers and volunteers, who are always treated like close friends. The board also includes tip sheets, like “how to read a nutrition label.”