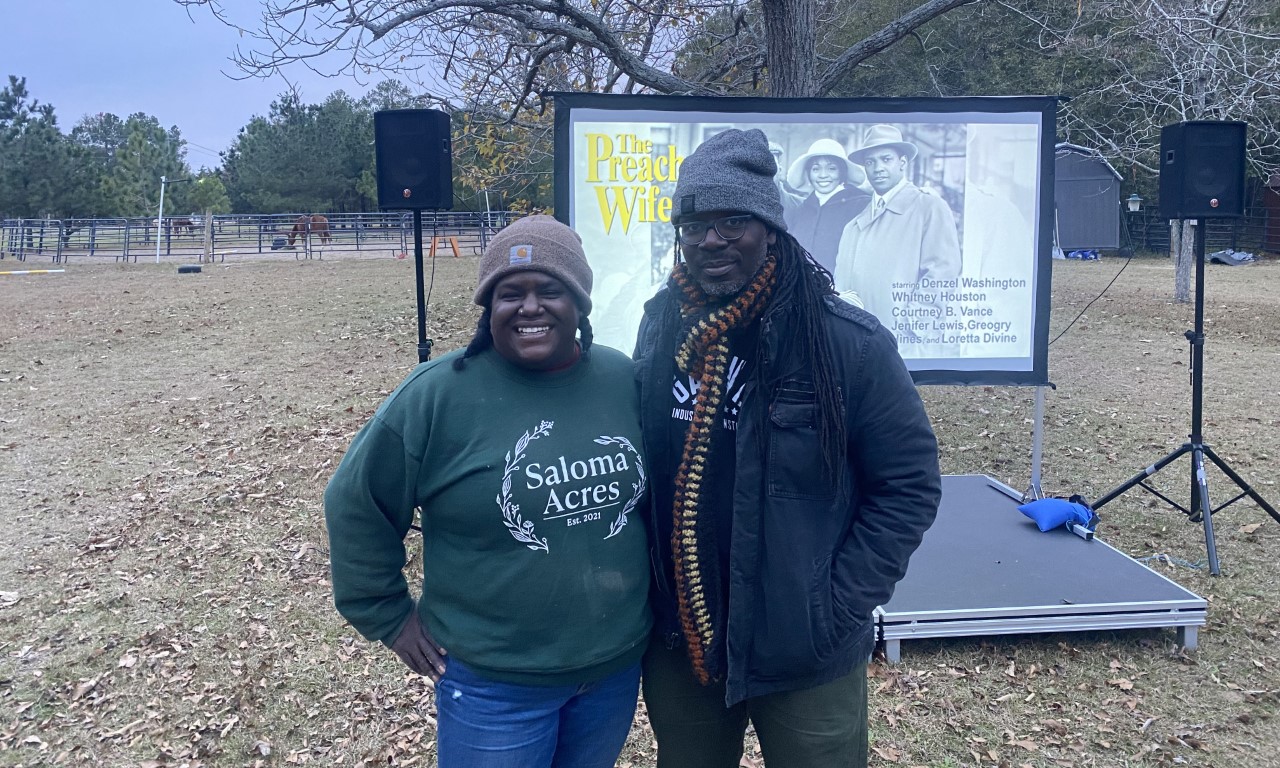

Kenya Cummings and her husband, Marcus Heyward, travelled from Charleston to Columbia to attend Luminar Theater’s latest outdoor film showing. (Photo and video by Shakeem Jones)

Kenya Cummings and her husband watch the movie the “The Preacher’s Wife” every Christmas. It holds special meaning for them.

“It’s the ‘Preacher’s Wife,’ which I’m a preacher’s kid. Me and my family watch it every year,” she said. “We know it’s the holiday season when we watch it all together.”

But this year, the couple traveled more than two hours from Charleston to a private farm near Blythewood to see the movie.

Why?

Because this private farm near Blythewood is one site where an organization called the Luminal Theater shows Black cinema to various Black communities in the Midlands.

The theater does more than just show movies on farms. It provides an opportunity for Black, independent and, soon they hope, local filmmakers to showcase their work. Because seeing black cinema in person with others isn’t always easy these days.

One of the theater’s missions is to make films and filmmakers accessible beyond film festivals and streaming services, allowing them to be viewed in a collective environment, according to its website.

“We’re going to bring (films) to your neighborhoods,” John said. “We’re going to make sure that you know you were able to see them. We’re going to make sure that you know they exist, and you could watch them with audiences that share your background.”

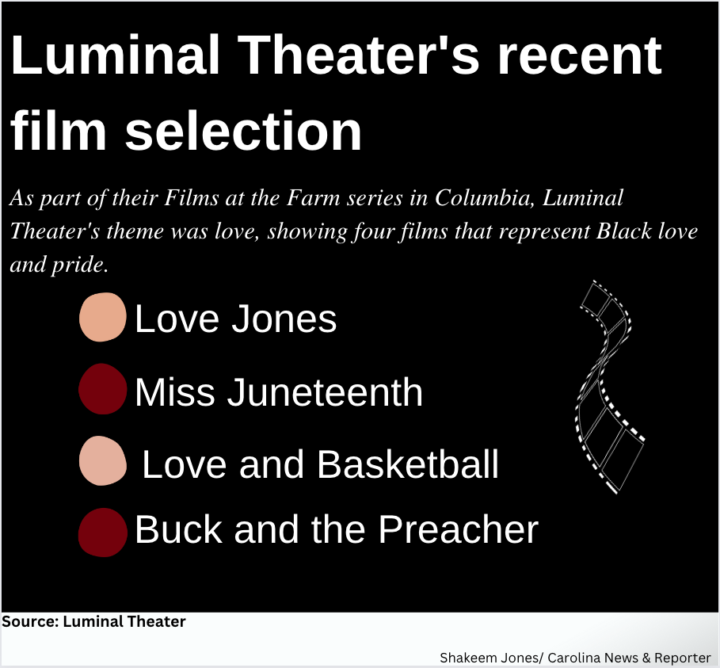

Defined as a “nomadic cinema that brings Black film straight to the people,” Luminal Theatre does not have one set home. Instead, it shows its selection in a variety of locations, such as the Spotlight Cinemas Capital 8 movie theater and the 701 Center for Contemporary Art. It recently has shown films such as “Love Jones,” “The Color Purple” and “Eve’s Bayou.”

“Our mission is to bring Black cinema directly to Black neighborhoods and to Black folks everywhere,” said Curtis Caesar John, founder of the organization.

Cummings said, for her, the past few weeks have been filled with difficulty. She thought the idea of seeing a movie that is special to her with other Black folk would be cathartic.

“Being able to be around Black folks on land that has been set up to experience outside and joy and play feels like what we needed,” Cummings said. “So we got in the car and came on down.”

The movie, about an angel who helps the preacher of a predominantly Black community with his struggling Baptist church, is a Christmas staple for the Luminal Theatre.

John said showing “The Preacher’s Wife” as one of its last films each year is fitting. The film is a remake of the 1947 film “The Bishop’s Wife.” While the 1947 film had an all-white cast, the “Preacher’s Wife” showcases a Black ensemble, starring Whitney Houston, Denzel Washington and Courtney B. Vance.

The Luminal Theatre began in the Bedford-Stuyvesant area of Brooklyn, N.Y., in 2015 as a means for Black artists and filmmakers to show their work.

The organization began showing films on street corners, in parks and community gardens.

“Those are places where people either already congregate or should be congregating more,” John said. “And so it’s kind of like there was a duality to it, in which people would be able to, you know, utilize that space more because it’s space made for them and come together to watch films that’s made for them, by them.”

In 2019, when John and his wife moved to Columbia – her hometown – they brought the theater concept with them.

They now show films at Saloma Acres, their 22-acre private farm, which also includes trails, picnic tables and horses.

On one recent evening, horses were in view behind the make-shift movie screen, which was set up under a tree bare of leaves from the changing seasons.

“There’s something about being in the middle of nature, something about being surrounded by trees, and there’s a pastoral feel that you get, so when you’re watching any film in that setting, it just brings a whole new feeling, a whole other experience,” John said.

An experience worth driving two hours to be part of.

“To be out in a Black space that was created for us to be outside, particularly when we live in South Carolina, it’s hard to find spaces that you can go to, to experience nature and feel safe,” Cummings said.

This showing had about 10 guests in attendance. Sometimes, there have been around 30 people, John said.

Some people bought tickets but didn’t attend, he said.

“It depends on the film, it depends on the weekend — we’re doing this for cultural and social reasons,” he said, not just to make money.

John said it’s harder to do things in Columbia versus Brooklyn. Here, because it’s harder to get people’s attention.

“In Brooklyn, you can reach more people with direct marketing than you can in Columbia,” he said, referring to subway ads that are seen by millions daily in NYC.

However, “Our thing is, we don’t need big crowds, we need enthusiastic crowds, and that’s what we had.”

The film industry dates back to the late 1800s, said Susan Courtney, a film and media scholar at the University of South Carolina. And its early decades did no favors to Black people.

“In the Hollywood cinema in the ‘30s and ‘40s, there was no critical lens,” Courtney said. “It was just the protagonists of films were white people and black people were dutiful servants.”

Courtney referred to the 1915 film “Birth of a Nation,” which depicts the rise of the Ku Klux Klan as American saviors in the Reconstruction era. The film depicts Blacks as ignorant sexual predators of the white population of South Carolina.

“The film is this whole white supremacist fantasy that equates black political power with a black sexual threat,” Courtney said. “And so I think it’s an interesting example of how Hollywood cinema has often worked, where it’s had representations that are really unacceptable by many.”

Courtney said Black independent cinema rose during the same time period, noting Black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux’s 1920 film “Within Our Gates,” which served as a counter narrative to “Birth of a Nation.”

“(Micheaux) is showing films in segregated theaters, so his films aren’t being seen by white audiences in mainstream movie houses,” Courtney said. “They’re seen by Black audiences in small theaters.”

Luminal Theater tries to highlight those Black filmmakers, then and now.

“They tell our stories in a more realistic way, kind of like in a more sensitive way than most Hollywood films do, and that’s the big difference,” John said.

Andrew Gajadhar, executive director of the Carolina Film Network, said there is a lot of great storytelling going on in Columbia.

Founded in 2015, Carolina Film Network is a membership non-profit that offers aspiring filmmakers classes in screenwriting, production and directing.

“Black cinema is our release valve,” Gajadhar said. “We have all of this pressure that’s put on us by society that we have to overcome, that we’re expected to be strong enough to overcome because historically that’s what we’ve done. And when it comes to Black cinema, (all that pressure), that’s all released. That’s the way in which we are able to articulate our voice.”

Thaddeus Jones Jr., an independent filmmaker and founder of Fanatik Productions, which creates feature and short films, said Black filmmakers are starting to gravitate towards genres that haven’t been typically done by Black filmmakers, such as sci-fi and horror.

Jordan Peele may be the most prominent Black filmmaker in the horror genre at the moment, with films such as “Get Out,” “Us,” and “Nope” grossing more than a total $680 million at the box office.

“Now the barrier to entry for people who want to make films is lower,” Jones said. “And to make a good quality film that has the ability to to bridge the gap between Hollywood and independent is even lower than it was (just several) years ago.”

John said he wants to show more films by local, independent filmmakers in 2023.

“We’ve been gathering a lot of films from local filmmakers in Columbia and nearby to be able to showcase their works more — and to be able to have audiences understand that you’re capable of doing this, too,” he said. “You’re capable of making a film. You’re capable of reflecting your community stories, your family stories, through this.”

Cummings said she was sold on the showing at the Luminal Theater when she was told she could sing out loud. “The Preacher’s Wife” soundtrack is sung by Whitney Houston. It sold 6 million copies worldwide, making it the best-selling gospel album of all time.

“So many places that have been created for us to rally are also usually connected to pain, like the number of protests that have happened over the last couple of years,” Cummings said. “So, to have a space just about joy, it just reminds me Blackness is not all grief – it’s not all pain.”

Luminal Theater has shown movies in locations including Spotlight Cinemas Capital 8 and 701 Center for Contemporary Art.

Curtis Caesar John and his wife, DeLana Dameron-John, own and operate Saloma Acres, a private farm near the Blythewood area where they show select films through the Luminal Theater.