Members of ‘Stop Offshore Drilling in the Atlantic,’ an organization that intends to prevent offshore seismic blasting and drilling, protested outside the South Carolina State House in March.

Credit: Logan Anderson.

Page 1 of Executive Order 13795, passed by President Trump in an attempt to promote domestic energy production.

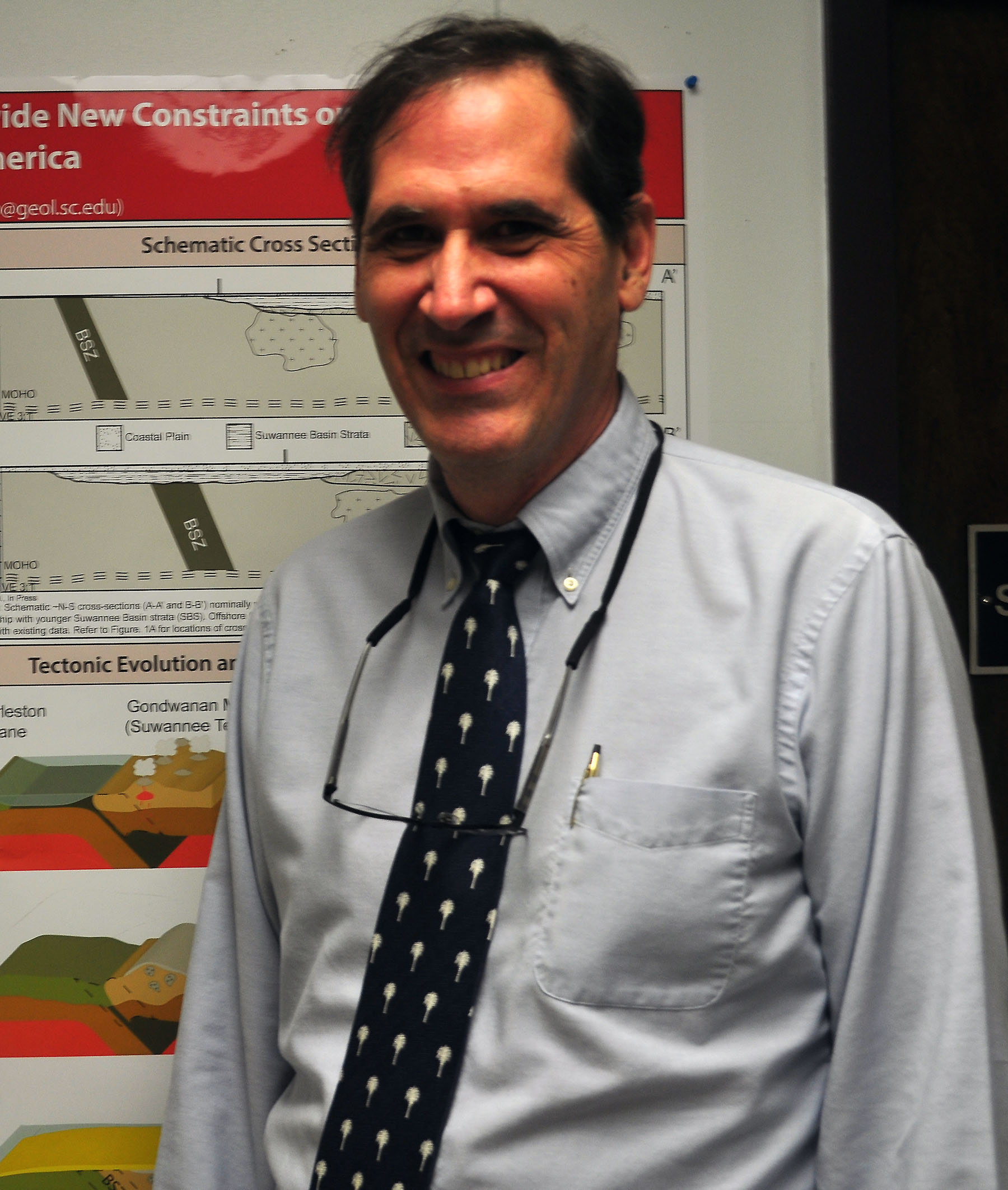

James Knapp, a geology professor at the University of South Carolina’s School of the Earth, Ocean, and Environment, has worked in the petroleum industry and testified as an expert at several congressional hearings.

The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the southeastern United States. Established in 1982 by the United Nations’ Convention on the Law of the Sea, countries are able to claim everything between 3 and 200 nautical miles off their respective shorelines for economic purposes.

Credit: South Atlantic Fishery Management Council

The current proposed lease sales program for 2019-2021, allowing energy companies to bid on areas for drilling.

Credit: Bureau of Energy Ocean Management

Since 1953, the vast Atlantic Ocean has been largely untouched by the petroleum industry. By early 2019, almost all of the United States’ protected reservoir could be up for auction.

It would also be the first time in history that almost all U.S. waters – including those off the coast of South Carolina – would be open to drilling.

Last April, President Trump issued Executive Order 13795, outlining an “America First Offshore Energy Strategy.” In its effort to roll back Obama era regulations and increase domestic energy production, the Trump administration is working through the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) to produce a five-year plan for sustainability.

President Trump has already started by appointing Scott Angelle, a Louisiana native who has openly supported rewriting safety and environmental rules implemented by the Obama administration, as the head of the BSEE.

“Help is on the way,” Angelle told oil and gas executives last year, the New York Times reported.

The BSEE was created under Obama to enforce safety protocols in the wake of the 2010 BP Oil Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. The drilling rig explosion killed 11 and contaminated the Gulf with a spill the size of Connecticut.

If President Trump’s plan is approved – a process of revisions and changes that takes between 18 and 24 months – it would be effective through 2024.

University of South Carolina geology professor James Knapp has worked in the petroleum industry for several years and understands the continued need for fossil fuels as part of an “all-of-the-above” energy outlook for the foreseeable future.

“While we transition to renewable and alternative energy sources, hydrocarbons will continue to be a critical part of our national energy portfolio,” Knapp, 56, who teaches at USC’s School of the Earth, Ocean, and Environment, said.

The 1982 United Nations’ Convention on the Law of the Sea allowed countries to claim jurisdiction of coastal waters for economic purposes up to 200 nautical miles off their respective shorelines. Since then, around 85 percent of the Atlantic and most of the United States’ waters, excluding the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska, have remained untapped.

With the push to loosen drilling laws, Knapp estimates 97 percent of U.S. waters are now under consideration.

However, if the oil industry sees a future in S.C., the tourism industry sees a potential threat to their main income source.

Julie Ellis, 50, public relations and communication manager for Myrtle Beach’s Chamber of Commerce, is worried about possible loss of tax revenue for her state.

“We support energy independence, but not at the risk of our number one industry,” Ellis said.

Specifically, the Myrtle Beach area alone covers 60 of S.C.’s 187-mile coastline.

South Carolina politicians are opposing the plan as well. Rep. Mark Sanford, R-S.C., and Gov.Henry McMaster have publicly denounced the president’s proposed changes. Other states, including Florida and New Jersey, are pursuing anti-drilling legislations or exemptions – fearing they might experience a drop in tourists.

Jason Ryan, director of communications for BP Oil in Houston, says BP favors increased access to available hydrocarbon resources in the Atlantic.

Ryan said in a phone interview that if the initial seismic data were promising, the company could seek to drill exploratory wells in the area and begin collecting preliminary data.

In order to determine if an area is “oil rich,” data from past seismic surveys – a method which uses sound energy to probe the upper 10 kilometers of the continental shelf – must be reviewed and analyzed by BSEE and BOEM. Then, that information is given to companies like BP to help them determine where they should begin looking for oil.

But Knapp was adamant that the data being used is outdated.

“Since the Atlantic has been off limits, data hasn’t been collected from that area since the ’70s,” Knapp said, “We really don’t know what’s going on down there.”

Through April, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has taken over 1,000 days to approve permits to begin seismic testing for the Atlantic. The standard lead time for permits is around 120 days.

Knapp isn’t surprised by the delay, but reaffirmed the need for a modern data set.

“Even if a resource were to be discovered, it would take a better part of a decade to develop,” Knapp said.

According to BOEM’s website, leasing sales for the Mid-and-South Atlantic could begin as early as 2020.