Employees work behind the counter of Drip, a coffee shop in Five Points. (Photos and graphics by Tyler Fedor)

Brian Glynn has owned Village Idiot Pizza since 2013. He has just under 50 employees across three locations in Columbia.

He would like to have more employees, but the cost of labor is too high.

“The only reason (labor costs are) not severely curtailing things is because we can never have a full staff,” Glynn said, referring to his profits.

In November, the South Carolina Department of Employment and Workforce said the average hourly wage in South Carolina rose 2% in October from September, from $28.45 to $29.11.

Wage growth in recent years has been primarily driven by a labor shortage, said Joey Von Nessen, a research economist at the University of South Carolina’s Darla Moore School of Business. The labor participation rate in South Carolina as of October 2022 was 56.6%, according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve. The last time the percentage was at or above 60% was in 2013.

The rate is defined as the percentage of people 16 years and older working or actively looking for work.

While the rate has been declining since 2013, Von Nessen said it was exacerbated in recent years due to baby boomers retiring en masse during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time, baby boomers made up the majority of the workforce in the United States. When they began to retire, there were not enough workers to fill their shoes, Von Nessen said.

“As a result, we have a lower labor supply,” Von Nessen said. “And that puts workers in a much stronger position to be able to negotiate. So that’s driving wages up, which is good news for individual workers.”

But not so good for businesses.

Steven Cook increased the starting wage at his Five Points restaurant, Saluda’s, from $10 to $12 an hour when the pandemic began. The wages for a skilled worker, someone he said could work a grill and run a kitchen, have risen beyond that, he said.

“At the end of the day businesses, they’re all chasing customers, but they’re also chasing employees,” Cook said.

He said he has raised wages not just in an attempt to attract more workers but to keep up with the growing costs employees have, such as food and rent.

Prices for some of Saluda’s meals have risen to make up for the increased wages for his 48 employees, Cook said. But he said the restaurant is “busier than we’ve ever been before.”

“There’s this old saying in the restaurant business – sales cures all,” Cook said.

Sean McCrossin, the owner of Drip, a Five Points coffee shop, said he raised wages and added benefits since the COVID-19 pandemic to try to attract workers. The benefits include $50 toward healthcare and one hour toward a vacation day for every 32 hours worked.

He said about a year and a half ago he raised his starting wages for his 21 employees “a dollar more or so.”

“A dollar raised to my employees takes away from quite a bit of the bottom line of what we have,” McCrossin said.

But, like Cook, McCrossin said customers are willing to accept the increased prices of his coffee products and said tips are “a lot better than they’ve ever been.”

He noted most of his employees are on the lower end of his wage range, but declined to share details.

Both McCrossin and Cook have said they have had relatively stable work forces as wages rise. Glynn, though, said he still struggles to attract and retain workers.

Village Idiot, he said, is still 30% understaffed. And he said he works every day to cover a shift in one of his locations. The starting salary before the pandemic was $9 an hour and this year was raised to $11.

Glynn also has to train new hires regardless of experience. Someone with experience making pizzas or performing a certain job in the kitchen could take only a few shifts to train, while a fresh face could take two to three months.

“It gets real frustrating when you do it for two months and they just stop showing up because somewhere else is now giving them $12 an hour instead of $11 and you have to start all over again,” Glynn said.

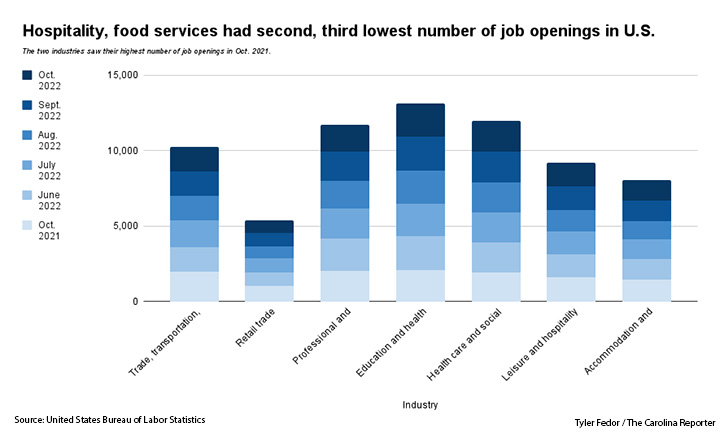

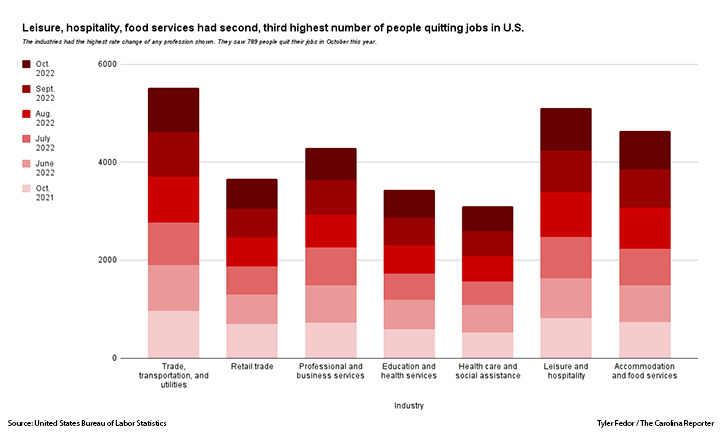

Von Nessen said a situation like Glynn’s is a “very common complaint” from employers, even as the hospitality industry is seeing the largest wage growth when compared to other business sectors. Von Nessen said plenty of restaurants, bars and hotels are having to not just raise wages but offer other benefits, as McCrossin has.

Higher wages and a labor shortage are not going away anytime soon, though, Von Nessen said. The shortage is more pronounced in South Carolina, which has a lower labor participation rate than the national average. Von Nessen said that’s because the state has a higher percentage of retirees than the national average.

While wages will continue to rise, Von Nessen sees the pace of growth slowing. COVID-19 created unsustainable demand for some products, and eventually the demand will fall. As demand falls, so will the demand for labor.

Until that happens, though, Glynn is going to continue working in the kitchen and operate using a limited menu. Plus, he said he’ll have to close on certain days to avoid worrying about filling certain shifts. He said he’s “just throwing bad money” away hiring and training people who will stop showing up for work soon after.

“It consumes our thoughts all the time,” Glynn said.