Tigger, the name given to one of the many community cats residing around Williams-Brice Stadium, comes out at dusk. (Photos by: Samantha Winn)

On most nights, 20 stray cats and kittens lounge around the Cockabooses at Williams-Brice Stadium. Most of these cats will soon be destined for homes, thanks to Nickol and Craig Gallivan, a Columbia couple who discovered the feline community on a walk four years ago.

“Honestly, we saw one cat and then we realized that she had five babies and we started feeding them,” Nickol Gallivan said. “We were trying to make sure that her and her babies had food and water because she was looking very thin trying to nurse them. And so, we kept trying to do the right thing.”

The Gallivans, who live in a residence near the stadium, work as medical sales representatives but they are also animal lovers with several of their own pets at home.

Soon, the number of stray cats coming around for food and water increased. And so did complaints and threats of fines from neighbors near the stadium who opposed the presence of feral cats. The cats wander around the bright garnet stationary rail cars that stretch from Key Road to Bluff Road, which are outfitted for luxury tailgating just outside the stadium. Outfitted for luxury tailgating just yards from the stadium, the Cockabooses sell for $250,000 and higher and rarely come up for sale.

The Cockaboose homeowners association declined to comment on the cats, although the Gallivans understand the stray felines have been a topic of conversation at HOA meetings.

“We’ve had a lot of things thrown away over there,” Nickol Gallivan said. “We’ve gone and we’ve supplied feeders, waters, everything.”

The HOA for the cockabooses have reported problems with air conditioning ducts due to animals, according to Nickol Gallivan. But the couple says opossums and raccoons also frequent the area, sometimes interacting with the feral cats. The owners, through the association, could not be reached for comment about any problems with ductwork due to animals.

“To think that these cats are the ones causing the devastation to people’s property … my thing is why don’t you look to control and contain the actual creature that is causing the devastation, which is the opossums and raccoons,” Craig Gallivan said. “These cats are not causing any trouble. They are looking to go and hide and on game day.”

Once they committed to feeding the cats, the Gallivans said they began to figure out how to humanely trap the cats and bring them to adoption centers.

“We feel like we are responsible for them now because we know about them, so how can I rest my head at night and know that there is an animal starving and we have something that we can do about that,” Nickol Gallivan said.

In four years tending to the stadium-area cats, they have fed over 70 cats and humanely trapped 55 cats. To their knowledge, only one has been released back.

“Our goal really when we prep them is just to get the young ones, make sure that they are able to be adopted, that they can be fixed and that they are not going to be ones to be put back out,” Nickol Gallivan said.

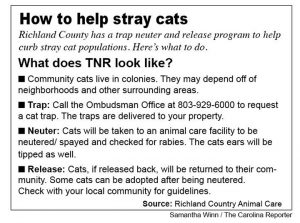

The Gallivans availed themselves of a Richland County program known as Trap Neuter and Release. By bringing in stray cats to the Humane Society, veterinarians can treat cats for rabies and spay or neuter to help control the population.

“It is very important for the community to take care of these ferals,” Dawn Wilkerson, executive director of the South Carolina Humane Society, said. “Unmanaged colonies can reach thousands and thousands of cats if kept unchecked and then what typically happens is that these diseases spread through these communities.”

Diseases can be transmitted to domesticated cats through grass, soil and water if colonies are left alone.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Gallivans have noticed how quickly animals at the Humane Society are getting adopted.

“People feel trapped or indoors,” Craig Gallivan said. “They need a sense of companionship and relationship to get them through. Cats and dogs up there are not being kept for an extended period of time.”

“I hate what COVID has done in many ways because I have already lost a parent during these times and it is hard,” Nickol Gallivan added. “And so you want to help anyone who is lonely and I think these cats have done that.”

Working with Pawmetto Lifeline, another animal welfare shelter in Columbia, the two animal groups will be arranging TNR efforts across the county.

“We are going to focus on different zones and different areas of the county,” Wilkerson explained. “It has been shown that if you work a certain area with striving to spay neuter vaccinate and return, it will take down the cat population and keep the cat population down.”

Pawmetto Lifeline will be working on TNR efforts in the northern and western parts of Richland County, while the Humane Society will be working in the southeast and northeast sections.

University students have adopted from the stadium cat colony. Sophomore biology student Savannah Keating adopted a white kitten named Suki.

“You would think living on the street right here basically she would have something, but she’s perfectly healthy,” Keating said. “She’s under three pounds so she’s not spayed yet or anything, but she’s such a good girl.”

Their daily routine of going to the Cockabooses has been a source of happiness for the Gallivans. It’s something they plan to continue.

“If people feel comfortable coming up and talking to two pretty sociable people, we welcome everybody to come out there and meet with us and support us,” Craig Gallivan said. “We will continue to do this whether the lights are on us or not.”

Nickol Gallivan, who works in cardiology sales, feeds the cats around USC’s football stadium in her free time.

Nickol’s efforts started with two cats she saw roaming the area and has expanded to caring for many.

Nickol has spent four years tending to these community cats.

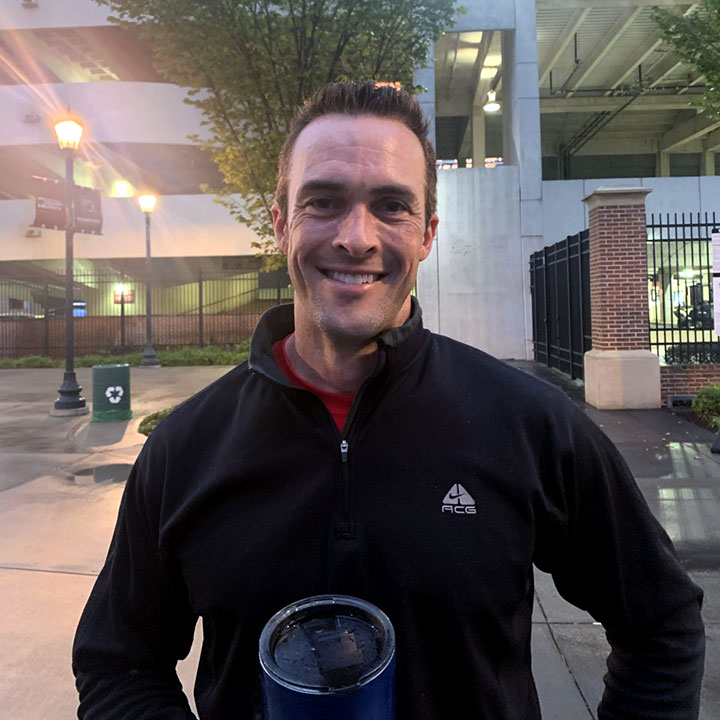

Craig Gallivan helps his wife caring for the cats around the stadium.