The sign at Hand Middle School in Columbia is one of many in the state calling for new hires. Photos by Cora Stone.

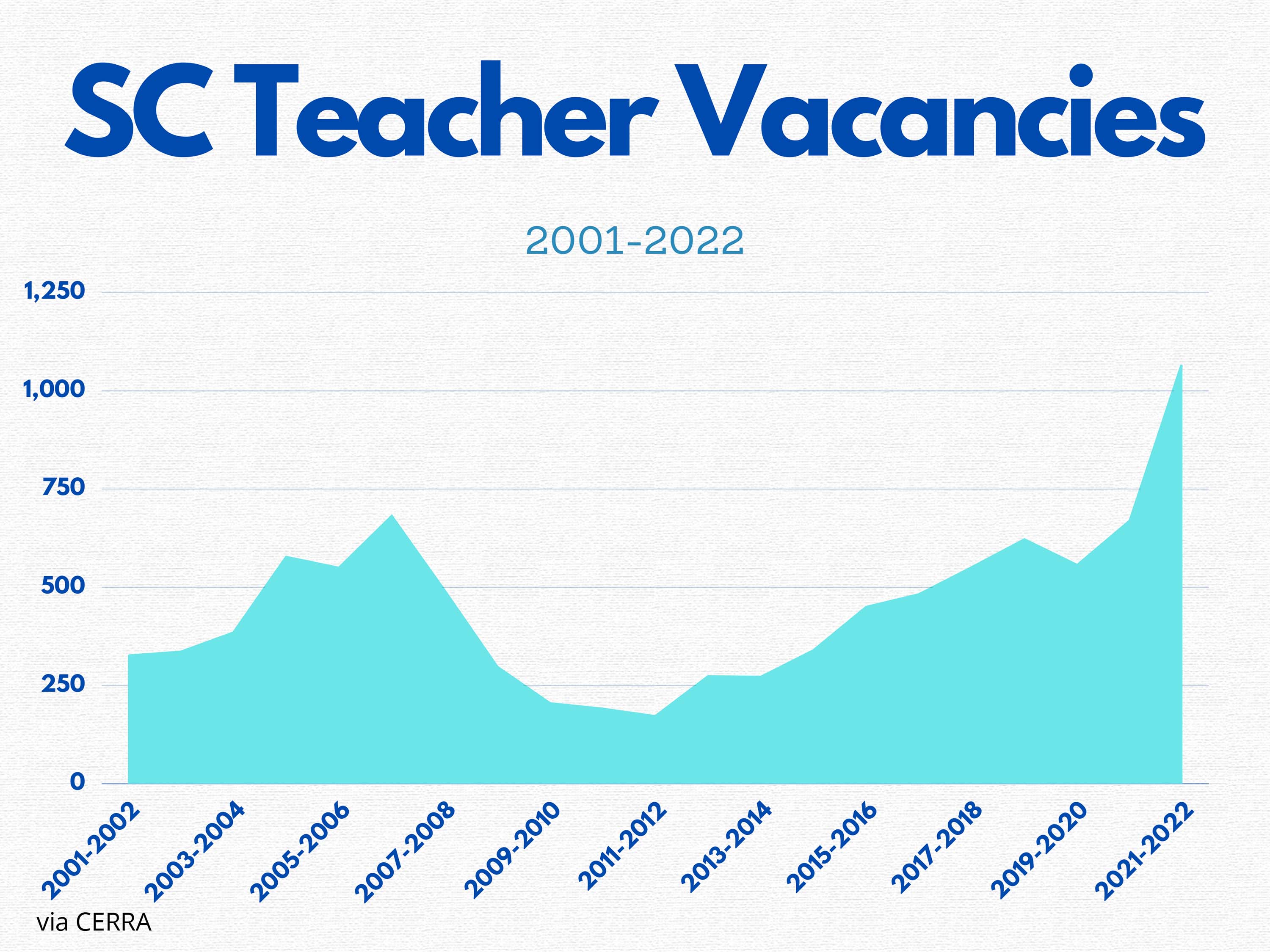

Ten years ago, there were about 170 vacant full-time educator positions at the beginning of the school year in South Carolina. This year, there were 1,060.

This 520% increase is the canary in the coal mine for South Carolina’s public education system and unveils deep fissures in the structure of support for public educators.

“It’s pretty striking that overall, we are seeing that trend of educators leaving the profession,” said Derrick Hines, the Teaching Fellows campus director and Teacher Cadet College coordinator at the University of South Carolina. “It’s something we’re trying really hard to combat.”

Organizations like the South Carolina Education Association and the Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention, and Advancement at Winthrop University provide resources and support to teachers across the state. The Teaching Fellows and Teacher Cadet program are part of CERRA.

The CERRA Supply and Demand Report collects data and information regarding teacher retention. According to Hines, the numbers have been concerning for many years.

Teacher vacancies at the beginning of the 2021-2022 school year were the highest since the first report in 2001.

But perhaps even more troubling are the departures of veterans from the classroom. The report showed that 6,927 left teaching in 2020-2021. Of those, 1,859 educators in the latest report did not provide a reason for leaving. CERRA Executive Director Jenna Hallman said that many teachers leaving the profession will not provide a reason or select “personal reasons” as a catch-all in order to maintain relationships with school districts.

“What I’ve been able to collect from teachers across the state is that is what they’re going to say if they don’t want to burn that bridge,” Hallman said.

For several years, the South Carolina Legislature has promised to bolster teacher salaries and provide significant resources, but has failed to pass legislation that would significantly overhaul the system, teachers say.

Former Lexington School District 1 employee Kelly McElwain said the public’s disdain for educators during the pandemic was enough to make her leave the profession of teaching.

“I absolutely loved my school, the administrators, my colleagues, the parents, and the community. I thought that I would stay there until they made me retire,” McElwain said. “But with the attitude of the general public towards teachers during the pandemic, the completely dismissive attitude that the public had, I decided that’s enough, I’ve had enough.”

McElwain only planned on taking one year off from teaching to take care of her daughter who was having surgery while her husband was working out of town. After watching the legislature and the public’s attitude towards teachers during that time, she decided not to return.

“We have expected the public school system to do more than educate kids for decades. We’re supposed to be medical providers and mental health providers and feed them and clothe them and the communities are not stepping up to support families who need these things,” McElwain said.

Even veteran teachers and administrators are leaving the profession, with many going into the private sector, McElwain said.

“Their specific skill sets are very valued there. So you see teachers who are going into the private sector and making significantly more money, are valued and appreciated, and are told when you go home at 5, we don’t expect you to respond to emails,” McElwain said. “I think there is just a lot of fatigue.”

Less planning time, lack of duty-free lunches and expectations to cover additional classes cause teachers to work well into their personal time.

“There are people who take their work home on weekends, they come in early and they stay late, and they cannot get it done,” Sherry East, president of the South Carolina Education Association, said. “It’s the working conditions. It’s not necessarily the pay; it’s what you’re paying us to do and what you’re asking us to do. It’s too much.”

A continuation of this problem will have a detrimental effect on classrooms, experts say. It will mean larger class sizes, additional teacher workload, and less variety in courses that districts can offer.

“My working conditions as a teacher are your child’s learning conditions. You’d want those to be the best they can be, so we need to use as many resources we have into fixing this crisis as soon as possible. We can’t wait any longer,” East said.

While the pandemic has exacerbated teacher burnout, this is not a new problem nor one that will be solved any time soon, according to Hines. Positive change requires shifting the narrative to support public educators and including them in decision-making conversations.

“To be able to have that support to say, ‘We’ll invest in systems that will allow you to have unencumbered planning time or give you the resources necessary to make sure you’re attracting and retaining high quality educators,’ that’s something that should be considered and potentially could impact our education environment in a positive way,” Hines said.

Research shows that teacher vacancies are at an all-time high.

The South Carolina Education Association advocates for educators in South Carolina by providing resources like listening meetings where educators can talk about issues.

The SCEA provides support for teachers and advocates for strong public schools.