By Shayla Nidever and Mary Ramsey

This story is one in a continuing series covering the crisis in public housing in Columbia.

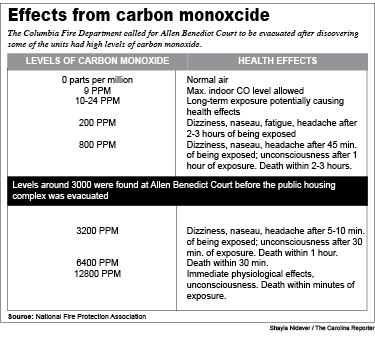

After two men died from carbon monoxide poisoning in a Columbia public housing complex, public safety officials and health experts are stepping up to warn the public of the dangers of gas leaks.

For those who study the effects of carbon monoxide, like USC researcher Robin Dawson, the deaths of the two apartment dwellers are a stark reminder of the importance of knowledge and accountability when it comes to gas leaks.

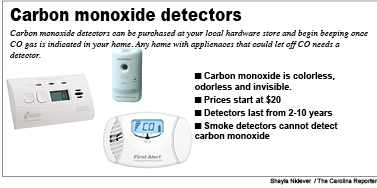

“A preventable tragedy, unfortunately,” she said. “Just for the lack of a $20 carbon monoxide detector. I just don’t understand it.”

Columbia fire chief Aubrey Jenkins, whose department responded to multiple calls about suspected gas leaks in the weeks and months leading up the abrupt closure of Allen Benedict Court in January has worked since to educate homeowners and renters about what to do in the event of a potential gas leak. More than 400 residents were rushed from their homes in the 1940s-era public housing complex.

Symptoms of carbon monoxide poisoning include dizziness and fainting, nausea, severe headaches, confusion and sleepiness. At least one Allen Benedict resident reported experiencing symptoms as far back at July 2018, according to a lawsuit filed by that resident.

If you smell gas or experience symptoms, Jenkins said your first step should be to call 911.

Emergency officials can address the immediate issue: testing the air, shutting off the gas at the meter if there is a leak and notifying the gas company. From there, it’s up to the homeowner, landlord or management company to follow up on the issue.

“When our firefighters respond to a call, they go out there for the sole purpose of taking care of the issue,” Jenkins said. “They don’t go through and do an inspection of the place. That’s not what their role is.”

That means, according to Jenkins, that individuals and property owners are responsible for keeping up with fire and building codes related to carbon monoxide.

About 500 people die each year in the U.S. from carbon monoxide not related to a fire, according to the most recent data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Exposure to carbon monoxide isn’t always fatal, but research suggests that it can also trigger long-term health issues, according to Dawson.

“Usually if you’re being exposed, once you remove the exposure, most people are going to recover fairly quickly and not have any long-lasting damage,” she said. “But there are researchers here in the U.S. and beyond that are starting to see that there can be permanent neurologic damage, especially within our more vulnerable populations.”

Children and elderly people in particular, Dawson explained, may be more prone to memory issues after exposure.

Jenkins stressed that the easiest way to prevent a carbon monoxide issue is to have monitors in all living spaces that use any kind of gas or have a fireplace.

“It’s odorless, it’s colorless, and you can’t see it. So that’s why it’s important to have a CO detector because at least that way you know if you have CO in your home or your apartment or whatever,” he said. “I just advise people to get it.”

Carbon monoxide detectors cost anywhere from about $20 to over $100 at home improvement stores, and some are plug-in, whereas others require installation. In South Carolina, any new home or older home undergoing a renovation that requires a building permit needs a detector if it has an attached garage or any appliances that run on propane, wood or other fuels.

Dawson said one of the most important factors is knowing what parts of your home are vulnerable to gas leaks and making sure detectors are able to catch them.

“The fact that we can’t see it, smell it, taste it, discern it in our environment means that we need carbon monoxide detectors,” she said.