By Shayla Nidever and Mary Ramsey

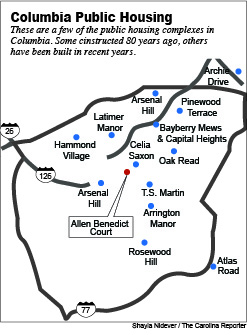

This story is one in a continuing series covering the crisis in public housing in Columbia.

Once a vibrant public housing community in Columbia, Allen Benedict Court sits vacant, battered and destitute, its residents scattered.

On Jan. 17, Calvin Witherspoon, Jr. and Derrick Caldwell Roper were found dead in their apartments in Building J at Allen Benedict, exposed to deadly levels of carbon monoxide. The deaths prompted the emergency evacuation of the 411 residents of the community off of Harden Street.

One month later, some Allen Benedict residents are still without permanent housing amid mounting lawsuits against the Columbia Housing Authority and unanswered questions.

“If you have the opportunity to go into one of those units, you would be appalled, said Hemphill Pride, a Columbia lawyer who is representing two residents of Allen Benedict. “Roaches, rats, bed bugs, sewage backing up; absolutely pure neglect… What you have is the City of Columbia and the Columbia Housing Authority, they’ve relegated themselves to slum landlords because that’s exactly what they are, a bunch of slum landlords to let people live in conditions like that.”

Residents say the 26-building apartment complex, built in the late 1940s, was riddled with problems, from crime to bedbugs and heating and air conditioning issues. Authorities had visited the complex at least seven times in 2018 because of complaints about odors and gas leaks.

Once Columbia Fire Department began investigating, traces of gas and cyanide were also found.

Columbia Fire Chief Aubrey Jenkins called for the residents of Allen Benedict Court to evacuate their homes after finding multiple deficiencies. Although CO monitors became a mandatory part of complying with fire codes in 2012. Not one unit of Allen Benedict Court was equipped with one.

“We discovered that they have no CO detectors, even some of their fire alarms were inoperable,” Jenkins said. “We just discovered gas leaks from around the stoves, burnt marks in the closets where they had their hot water heaters.”

One of these could have saved the lives of the two men who died. The Columbia Housing Authority has said they will be installing CO monitors in housing properties that need them.

“Basically you suffocate to death, and that’s the worst outcome. It’s a tragedy, a completely preventable tragedy, unfortunately,” said Robin Dawson, a University of South Carolina assistant professor who does research on the effects of carbon monoxide.

The young and elderly low-income residents of Allen Benedict Court were particularly at risk, according to Dawson.

But in the end, she said, “I want to say very firmly: everybody is at risk. It doesn’t matter your socioeconomic status, it doesn’t matter your race or ethnicity, everybody is at risk.”

For more about the effects of carbon monoxide, read our story here.

The order to evacuate left more than 400 people homeless with whatever they were able to take with them. From there, residents were placed in hotels around the city. Some were moved multiple times.

In the days following the evacuation order, Mayor Steve Benjamin spoke to the public about rallying to find adequate and permanent housing solutions for these residents.

“This is indeed an issue of significant public importance. It’s trying on our souls and our hearts,” Benjamin said.

It’s been a month, and many of these families are still without homes. The Columbia Housing Authority has issued HUD vouchers to these residents to find new homes. The Columbia Housing Authority did not return multiple requests for comment.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development voucher program requires low-income residents to pay 30 percent of their earnings after taxes in rent. These vouchers are accepted by various landlords, allowing recipients to live in complexes and homes not owned by the housing authority.

Though seen as a solution, some residents like Lavice Goodwin said they’re still working through housing issues.

Goodwin lived at Allen Benedict eight years before having to evacuate because of the gas leaks. Besides the leaks, Goodwin says she had to deal with a variety of issues while living at Allen Benedict including lax maintenance.

“I liked it, and then again I didn’t like it because when we have problems they don’t come and solve the problems. That’s the only thing that I didn’t like about it. Other than that, I wouldn’t tell nobody to go back in that place,” said Goodwin.

You can read Goodwin’s full story here.

Lawsuits are mounting in the wake of the closure of Allen Benedict.

Pride represents Benjamin and Deborah Hill in their lawsuit against CHA board chairman Bobby Gist and executive director Gilbert Walker. He said his clients are finding life after Allen Benedict difficult, even with a housing voucher.

Pride said his clients told him, “they want to give me a voucher to move, (but) I don’t have anything to move. I can’t take anything out of there because the bedbugs have just inundated everything that we have.”

“They don’t have a bedroom set, they don’t have clothes, they don’t have pots and pans, they don’t have anything,” said Pride.

Pride felt differently about the Allen Benedict Court he knew as a child growing up in a segregated Columbia.

“We thought that was where the rich people lived because the units were so nice and because they had a playground. It was just fabulous, and we all thought well of it,” he said. “Going from the white community paying deference to the Negro community by building the project, now, at my age, my own people run everything. An African-American mayor, an African-American city councilman, an African-American housing director. All people of color who would treat the people in the project less than the white community treated Negros by building it. It’s a shame.”

A total of five lawsuits have been filed so far in response to the events at Allen Benedict. The first was a class action suit claiming residents had complained about potential gas leaks before the incidents that shut down the complex. The mother of one of the victims then filed a wrongful death suit, and a resident hospitalized for exposure filed a personal injury suit.

Two other displaced residents have also filed suits related to the living conditions at Allen Benedict, including one who said he had to go to the emergency room for symptoms allegedly connected to gas leaks.

And the crisis at Allen Benedict could have ripple effects through low-income housing around Columbia, according to USC political scientist Todd Shaw.

Shaw, who researches housing policy and urban development, said that taking a large public housing complex out of commission can add stress to an already taxed system.

“It’s not easy, in the sense that the number of units overall are smaller than the need. And often there are families, you know as in the case of Allen Benedict Court, those families are in immediate crisis, who are in need of housing, who are effectively homeless until they can find a prospect for housing,” Shaw said.

Richland County Council has approved $150,000 to help residents of Allen Benedict. The council is set to meet on Feb. 19 to discuss how those funds will be allocated.

Hundreds of people were told to leave their homes at Allen Benedict Court after a carbon monoxide leak killed two men last month.

Lavice Goodwin lived at Allen Benedict Court for eight years until she was told to leave in the middle of the night.

Hemphill Pride, who spent his childhood playing at Allen Benedict Court, is now representing clients who claim the housing complex was ridden with bed bugs and maintenance issues.

Aubrey Jenkins, chief of the Columbia Fire department, called for residents of Allen Benedict Court to evacuate after finding carbon monoxide leaks among other life-threatening issues.

Robin Dawson, a professor at the University of South Carolina, urges everyone to have carbon monoxide monitor in their home to prevent more deaths.