Valinda Littlefield has been teaching at UofSC since 1999 and is one of the university’s first African American history professors. Photos by: Taylor Washington

University of South Carolina history professor Valinda Littlefield wants to be upfront: She had no intention to join another university commission, let alone one that aimed to reconsider the university’s historical footprint and take up thorny issues of slavery, white privilege and exclusion.

The last commission she served on spent three years working to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the desegregation of UofSC, and she needed a break after that time-consuming experience.

“It’s intense. I mean, there’s no way around it. That is what committees and commissions are about and we often don’t talk about that just bone-tired work that goes on behind the scenes,” she said in a recent interview.

But for the past year, she’s found herself sitting in a new cycle of never-ending meetings and engaging in extensive research once again because she’s reluctant to say no to work she believes needs to be done.

What could be more time-consuming than tracing the untold story of a 200-year-old university?

The university’s Presidential Commission on University History aims to re-examine the historical context and potentially rename buildings on campus that are named after controversial figures, including slaveowners and Confederate heroes. At the same time, the commission hopes its research will create an accurate, inclusive record of UofSC’s history that will be used by future generations of the university.

“Because it isn’t just about the names on the landscape, it’s about so much more. That is a big part of it, but it’s not the only part of it. And so, therefore, you’ve got to think about how do you sustain gathering underrepresented histories,” said Littlefield, one of three co-chairs of the commission and the only Black woman among the three, including former UofSC President Harris Pastides and Elizabeth West, the university’s archivist.

Recontextualizing the history of a university built by slaves means confronting uncomfortable truths about an institution many love and respect.

“It is no easy task, and Professor Littlefield and others should be commended for taking on what is an extraordinary opportunity and burden to come to grips with our university’s history, to help frame public conversation and to open the floor for some very serious and challenging debate about who we are as an institution,” UofSC history professor Bobby Donaldson said.

Donaldson has worked with Littlefield since they were hired together in 1999. He believes longstanding narratives about the university’s past haven’t always been accurate, and it isn’t uncommon for history to be rewritten once more perspectives and documents are presented.

While she knew her work on this commission would be a daunting task, Littlefield wasn’t intimidated by the sensitivity of the subject matter. As a historian, she said she is used to separating facts from emotions. Still, she feels that you wouldn’t be human if history didn’t affect you in some way. In fact, emotions are a big reason she believes there has been a pushback against commissions similar to UofSC’s.

“It’s this feeling of, you’re taking something away from me, from my ancestors. These are my ancestors and how dare you question their actions. People make it very personal,” she said.

The commission was created last summer by university president Bob Caslen after mounting pressure from the community following the murder of George Floyd. The subsequent Black Lives Matter protests brought the once dormant conversation about renaming controversial buildings on campus to the forefront.

The university’s biggest gym is named after a staunch segregationist, a women’s dorm is named after a 19th-century doctor who experimented on female slaves and the library in the center of campus is named after a well-known slave owner. For years, students and alumni have debated if the university has done enough to come to terms with its tumultuous past. Now, many have hope that permanent action will actually be taken.

Although many buildings on campus are named after prominent historical figures, Littlefield believes we can learn the most about history from the often-overlooked individuals who lived ordinary lives, which is something she wants the commission’s work to showcase.

Littlefield first became enamored with history after hearing family stories while growing up in her native Durham, North Carolina. As a child, she couldn’t participate in the storytelling, but she was an active listener.

“It just prepared me for what I’m doing now. That love of storytelling, understanding people’s lives, experiences that they go through and always knowing that people, ordinary people had fascinating stories. We just often don’t get to hear them,” she said.

After pursuing a career in business administration, she was encouraged to follow her passion and eventually received two undergraduate degrees in history and political science from North Carolina Central University. After getting married, she moved to Illinois and pursued her doctorate at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign for just $20 a semester, a perk for being a faculty member.

UofSC professor emeritus and South Carolina Public Radio host Walter Edgar was instrumental in hiring Littlefield at UofSC, as the university was searching for African American history professors.

“She made an impression, just a terrific candidate. Students loved her, she was an excellent colleague and she went on to become the director of the African American studies program,” Edgar said.

When she visited UofSC, Littlefield wasn’t sure she would accept the job because she wasn’t ready to leave the life she created in Illinois. However, the warm weather and warm reception from the people she met helped sway her mind. She fondly remembers being instructed not the open a gift from Edgar and his wife until she returned home.

“I get back to Illinois, there’s 16 inches of snow on the ground,” she said. “I fight my way into the side door to get into the house and open the box because now I want to know what’s in this box. I open the box and it’s camellias that they had picked from their garden.”

Academics can be very contentious, Edgar said, but he said that Littlefield is nothing of the sort. Edgar is also a member of the commission and said Littlefield’s personable nature is what makes her a perfect co-chair because she makes sure that everyone feels heard.

“It’s a very disparate group. You know, they’re alumni, they’re students and she’s somebody who can just deal effectively with folks regardless of who they are,” Edgar said.

“We don’t always agree,” Littlefield acknowledged, “but we’ve got great members and, you know, we’re civil to each other and we’re not supposed to agree. I don’t want to be on a committee where everybody is singing “Kumbaya,” that’s just not real life.”

A common argument against renaming buildings on campus Littlefield is used to hearing by now is that the commission will be erasing history. In reality, the commission has been scouring written records for conversations about when the buildings were first named so it can contextualize the university’s intentions.

Creating historical landmarks did much more than making sure that history wasn’t forgotten, she said. Littlefield cites the erection of the Confederate battle flag above the South Carolina State House during the height of the Civil Rights movement as an example.

She said the flag was a reminder of who was in charge and served as a tool to suppress the voices of those who weren’t. The flag was initially placed at the State House to temporarily commemorate the 100-year-anniversary of the Civil War in 1961. However, it wasn’t removed until 2015 following the horrific massacre at Charleston’s Mother Emanuel Church, where avowed white supremacist Dylann Roof murdered nine Black churchgoers.

When the flag was used in the Civil War, “South Carolina was predominantly African American, so when you’re talking about people of their times, who are you talking about? You’re talking about a minority, you’re not talking about the majority, because the majority were people of color,” she said.

Littlefield believes people feel threatened by the inclusion of new assessments because they have not been educated on the history that has not been there. Recontextualizing history people think they already know is one of a historian’s biggest challenges in and out of the classroom.

“To have someone like Dr. Littlefield who is trained in those areas; she brings an informed perspective to make sure that there is no silence, there is no gap, there are no oversights in recognizing and seriously documenting all the key individuals who are critical to our campus’s evolution,” Donaldson said.

Littlefield stresses that all the commission can do is give a recommendation, and the final decision is ultimately up to the university’s board of trustees. She knows that a big reason people are reluctant to join commissions is that they have seen their hard work shelved in the past. Although no one knows what the final outcome of this commission will be, Littlefield knows that their work isn’t being done in vain.

“With regard to the commission and certainly to Dr. Littlefield, the work we’re doing, and this is something she has stressed, the work we’re doing on the university’s history is just as important, if not more important than looking at the naming,” Edgar said.

For Littlefield, continuing to recontextualize UofSC’s history is just the starting point in preserving an accurate account of the university’s history and fighting for its future.

“I would like for the university to always strive to document and share its history, its inclusive history, and to make sure that the university is an institution that continually works at making people feel comfortable being on this campus and sharing their experiences,” she said.

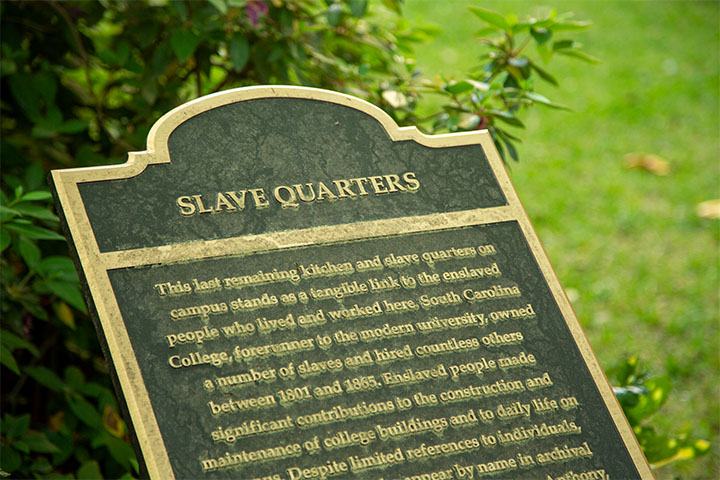

Littlefield cites the plaque that acknowledges the former slave quarters on the UofSC Horseshoe as a landmark that recognizes integral individuals who are often left out of the university’s story.

Littlefield said the statue of former UofSC women’s basketball star A’ja Wilson is a great example of a landmark that honors the diversity of UofSC’s campus.