Cicadas in South Carolina often come out and buzz during sunsets. Photo by Samantha Winn.

You can hear their mating call from a mile away. As a signal of summers in South Carolina, the cicada continues to buzz incessantly as a loud nightly chorus throughout the Midlands.

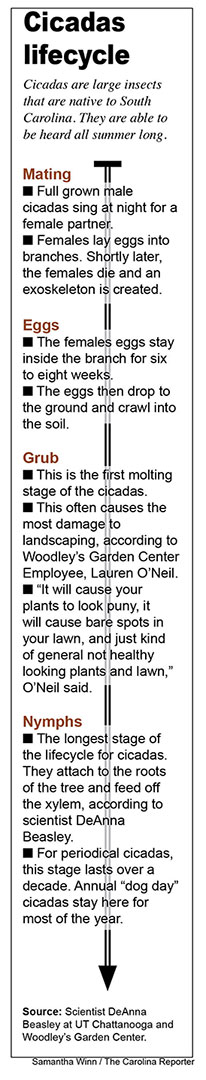

The insects, with lengths up to three inches, beady eyes and crystal-like wings, are native to the state. These alien-like bugs are harmless to humans and recur in periodical groups called broods every 13 to 17 years. Additionally, some cicadas emerge annually across the state.

DeAnna Beasley, an assistant professor in biology, geology and environmental studies at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, mapped out periodical cicadas extensively through the help of citizen scientists in her Ph.D. research in 2012.

“They emerge across the Southeast and kind of out into the Midwest. And we were getting a lot of calls and emails from citizens who were just interested in just understanding what is this that is happening in my backyard? Where is all this noise coming from?” Beasley said.

“We wanted people to just describe what they were seeing or hearing,” Beasley said. “If you see a cicada, take a picture of it so we can verify that it is a cicada, but if you hear it, that is a good indicator as well.”

Beasley used observational indicators and the help of citizen scientists in her doctoral and postdoctoral work at the University of South Carolina and N.C. State. She found that cicadas were more populated and larger in urban areas.

“They are in areas that are experiencing rapid change in landscape due to city growth and temperature changes as the climate gets warmer,” Beasley said. “It is pushing them further and further out of their tolerance range.”

Most of their life cycle occurs underground after the eggs are planted in hardwood trees. From there, they turn into grubs and migrate to burrow deep into the soil and attach to the roots of a tree. They can stay underground for over a decade.

During the course of a decade, the landscaping can change due to urbanization and climate change, according to Beasley. However, the cicada grub can still cause harm to young trees and shrubbery.

“So, it will cause your plants to look puny, it will cause bare spots in your lawn, and just kind of general not healthy-looking plants and lawn,” Lauren O’Neill, an employee at Woodley’s Garden Center, said. “If they (customers) are worried about the cicada grub eating at their plants, we do have a product that we recommend for them to put down. We do that once a year and it treats up to 7,000 square feet. It will help prevent cicada grub worms and Japanese grub worms from eating and destroying your landscape.”

Once the cicadas leave the ground, they only are active for four-to-six weeks during the heat and humidity of summer. For Ranger Bob Askins, a naturalist and volunteer at Congaree National Park, the cicadas offer a comfort during summer.

“I think cicadas are cool,” Askins said. “I like insects in general and I think they are fascinating and they are such a part of our life in this part of the world because you can’t really ignore them. With the discarded shells that you see around, but also the noise that they make, it’s pretty hard to ignore when they are really out in a force.”

Jon Manchester, another Ranger at Congaree National Park agrees. He witnessed a large brood cicadas in Maryland during their emergence in 2004.

“They are kind of alien. And if you don’t know exactly what it is, it looks kind of scary,” Manchester said. “Once people get used to them, they probably wouldn’t be as fearful of them.”

“I would just encourage people to be curious and to be excited,” Beasley said. “There is a lot about our biological world that remains to be explored, so having that sense of curiosity is going to take us far in that sense because there are still a lot of questions that need to be answered.”

A dead cicada sits on top of grass at Gamecock Park, near Williams-Brice Stadium.

Annual cicadas, most often known as the “dog day cicadas” emerge in late summer in South Carolina. However, periodical cicadas emerge in broods every 13 to 17 years.

According to research conducted by scientist DeAnna Beasley, cicadas are often larger and louder in urban areas. One of the factors of this is the “urban heat island” effect.