BLUFF RD., COLUMBIA: South Carolina’s active highway system are often be seen heavily littered. Photos by: Trey Martin

South Carolinians have an issue swirling right in front of them.

The COVID-19 pandemic has prevented state prisoners from picking up trash and limited the size of volunteer cleanup efforts. Meanwhile, unsightly litter collects in large numbers along roadways across the state.

Litter is not sedentary, as observed by Emma DeLoughry, who is pursuing a master’s degree in earth and environmental resource management from the University of South Carolina. After seeing the issue firsthand, she produced a documentary showcasing the effects of litter on the natural environment in South Carolina.

“My overall goal is to increase public awareness of this issue and make it the forefront of our agenda,” DeLoughry said. “I want people to realize that this is a serious problem and it’s not just like ‘oh, we have to save the turtles.’, Like no, it’s affecting us right here and it’s affecting us every day and we need to be concerned about it.”

The documentary, ‘Macroplastics in SC Waters: Connecting the Midlands to the Coast,’ seeks to educate viewers about the persistence of plastic material in the environment and show how the accumulation of this plastic litter causes significant environmental, wildlife and community damage.

Data from the South Carolina Aquarium’s Litter-free Digital Journal, a citizen scientist app that tracks collection numbers from litter sweeps, found the most common waste finds to be Styrofoam, food wrappers and film, plastic bottles, miscellaneous plastics and plastic bags.

These materials can be linked to fast-food containers, and the effects are visible in areas such as Rocky Branch Creek, which runs through Maxcy Gregg Park near UofSC’s campus.

“A lot of the waste from Five Points comes down the water here and gets trapped. A lot of the stuff that I found there was fast-food containers that were made of Styrofoam, especially Cookout cups and other Styrofoam containers from the fast-food places in Five Points,” DeLoughry said.

The lightweight and buoyant qualities of these materials make them easily transportable by wind and water. Once it reaches a water source, the flow can take it all the way to the ocean.

DeLoughry’s documentary examines the environmental, wildlife and community effects of macroplastics, which are plastic pieces larger than 2.5 centimeters. Plastic takes years or decades to break down in an aquatic environment, eventually becoming small enough to be consumed by other organisms in the water.

The extent to which the permanence of these materials impacts human life is staggering. As the energy moves up the food chain, so does the plastic, eventually making its way to humans in high levels.

The documentary also discusses the cost of plastic pollution in communities. She stated that Horry County spent an estimated $100 thousand a year repairing garbage machines that were clogged by plastic bags. Plastic bags can also clog storm drains and lead to flooding.

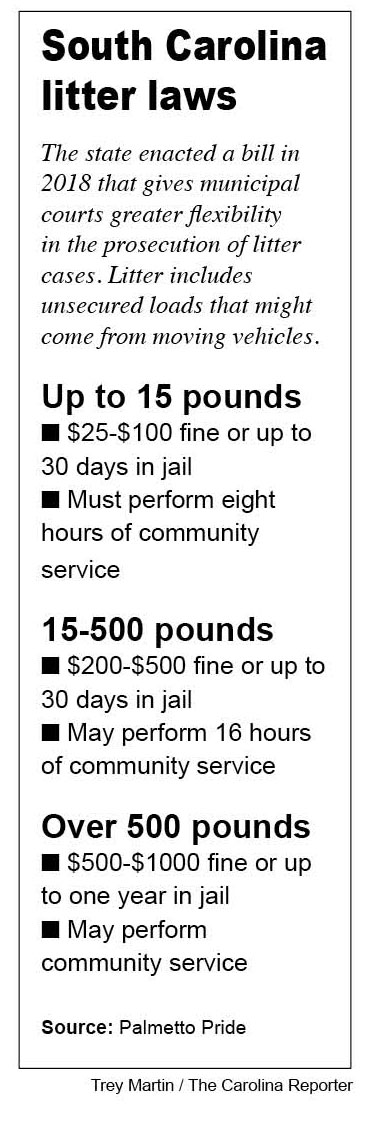

Groups like anti-litter and beautification nonprofit, Palmetto Pride, have already begun tackling the problem. The programs executive director, Sarah Lyles, explained how the state’s maintenance of its roads can put cleanup organizations at a disadvantage.

“The way we’re structured, we have a low tax base and we don’t pay for interstate pickup or county road pickup like other states might,” Lyles said. “We have a lot of people that come here. We’re heavily tourism based and trucks come through. We are a port state, there’s just a lot of traffic, and all of these things really impact litter at that level.”

Bill Stangler, the Congaree Riverkeeper, estimated that his organization cleaned up around 10,000 pounds of trash and debris a year prior to COVID-19. The pattern remains the same: floatable items get washed into the river, stuck on tree branches, or consumed by another organism at high levels.

“It’s a very visible problem, but it’s not the only problem. It’s one the average person can spend a few hours and help tackle. At the end of the day, these rivers belong to each and every one of us,” Stangler said.

Palmetto Pride also works with state and local government to enact anti-litter policy. While everyone wants to make their community better, Lyles said the complexities of dealing with waste management make taking action easier said than done.

“People think of litter as just being an eyesore, but there are so many moving parts. You’ve got solid waste and recycling and city, county, and state infrastructure, pickup, prevention. It is a lot more complex than just the aesthetics of it,” Lyles said.

State lawmakers and local officials have been at odds over who could regulate plastic containers. Advocates for the plastic industry argue that only the state’s General Assembly can regulate plastic containers, not local municipalities.

In 2019, S.C. state senators Wes Climer, R-York, and Scott Talley, R-Spartanburg, sponsored legislation which would not only prevent further plastic ordinances from being introduced by local governments but would undo all existing ordinances. This bill is still up for debate.

An average citizen can make an impact by reducing their personal waste consumption or volunteering at a local cleanup. Organizations exist in large numbers throughout the state and work alongside researchers like DeLoughry to address the issue that litter imposes on the environment.

DeLoughry will begin showcasing her documentary throughout the month of March. More information can be found on the documentaries website.

“I wanted to do something local that engaged the local community and the people who work here who are seeing this issue firsthand and working to bring attention to it and provide remediation,” DeLoughry said.

Emma DeLoughry, director of ‘Macroplastics in SC Waters: Connecting the Midlands to the Coast,’ became interested in the issue as an environmental science student at the University of South Carolina. Photo courtesy: Luismario Rosas Rivera.

ROCKY CREEK: Plastic bags are stuck on a branch at Maxcy Gregg Park on UofSC’s campus. Local communities around the country are debating placing a ban on plastic bags.

CONGAREE RIVER: Styrofoam fragments and aluminum cans never fully degrade and also leech harmful chemicals into the water.

GILLS CREEK: An increase in consumed fast-food during the COVID-19 creates more litter, which often makes its way into nearby water sources.