Sydney Lako, right, is a USC student who helps care for her grandmother, who has dementia. She often travels to her grandmother’s house in Rock Hill to care for her. (Photo courtesy of Sydney Lako)

Sisters Sydney Lako, 21, and Julia Lako, 20, were always excited about Christmas because their grandmother pulled out all the stops to entertain and feed the family.

But this year was different.

They entered the living room on Christmas Eve to find their grandmother hadn’t left the couch all day. She had forgotten to drink water all day — and forgot to use the restroom. Her mouth was so dry she could barely open it. And she was using pillows instead of a blanket to cover herself.

“That was really scary because we were also just like, ‘We don’t know what to do,’” Sydney Lako said. “’Do we call an ambulance? We can’t pick her up. … How do we clean her? How do we get her muscles not stiff anymore?’ So that one was a really scary moment because we were just like, … ‘grandma’s not even going to be here for this Christmas.’”

Their grandmother was diagnosed with dementia soon after, and they, along with their mother, have been caring for her ever since.

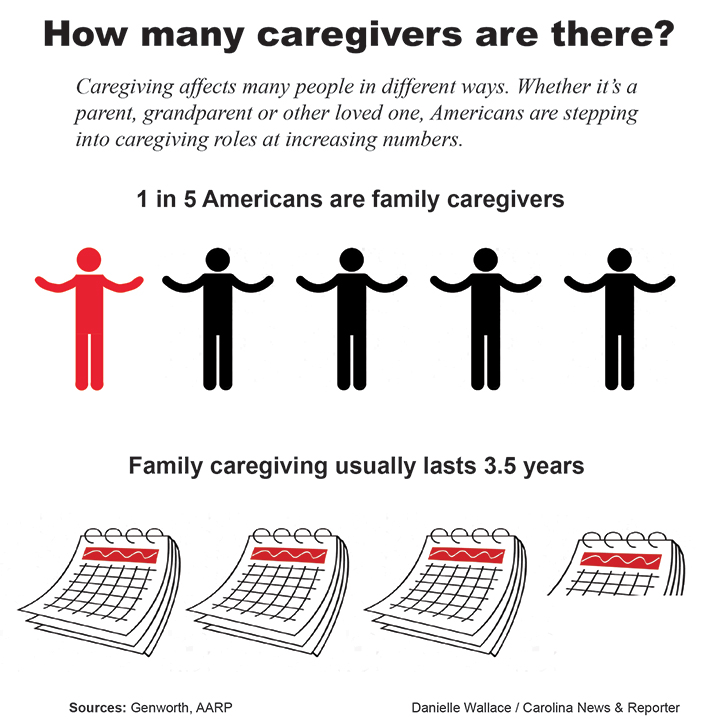

Similar to Sydney and Julia Lako’s situation, almost a quarter of all family caregivers nationally are between the ages of 18 and 34, according to the 2020 Caregiving in the U.S. report from the National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. More starkly, the report never included Generation Z caregivers until 2020, because there simply weren’t enough of them to count. But the newest report shows a massive change — 6% of all caregivers in the United States are now Gen Zers, or those born after 1997.

Although the average age of a family caregiver has remained the same at 49 years of age, more younger adults are assuming caregiving roles as life expectancy increases, according to the report. The large baby boomer generation is continuing to age and is living longer. That means boomers require more demanding care from their spouses — and younger generations.

“Caregivers are becoming younger, and so you’re not going to find that ‘60-and-60’ — meaning the care receiver is 60 and the caregiver is 60,” said Candice Holloway, the director of Central Midlands’ Area Agency on Aging.

Holloway said the organization provides resources, such as meal deliveries and senior centers, to caregivers. The organization is trying to reach these new, young caregivers.

“Anyone younger won’t know about us,” said Holloway, who is in her 30s. “The older people, of course they know about us, because we try to advertise (and) market in different areas that we know they frequent. … But people my age, … they’re like, ‘What is the Area Agency on Aging?’”

Still, Holloway said she has seen an increase in younger caregivers coming to the organization for assistance. She also has seen an increase in male and grandchildren caregivers.

FAMILY CAREGIVERS

Sydney and Julia Lako are full-time students at the University of South Carolina — and are now also caregivers for their grandmother in Rock Hill.

“We all get her medicine, we all feed her, you know, if she wets the bed, we all do laundry, we all strip the bed,” Sydney Lako said. “We all clean the house, you know. But Julia definitely does more of the cleaning stuff and we do all the ‘gross s—.’”

The “gross s—,” as the Lako sisters call it, includes bathing, dressing and cleaning their grandmother. They said this aspect of caregiving was abnormal to them because their grandmother is a very private person.

“It’s just not something I ever imagined I’d have to do,” Sydney Lako said. “It’s kind of surprising how well she has kind of taken everything. And I think it’s just really because she doesn’t fully understand what’s happening (due to her dementia). Because if she knew, she’d be mortified with what we were doing.”

When the sisters are away at college, their mom is the only family member around in Rock Hill, though a nurse sometimes drops in. Their mother makes the five-minute drive from her house to her mother’s house twice a day for check-ins.

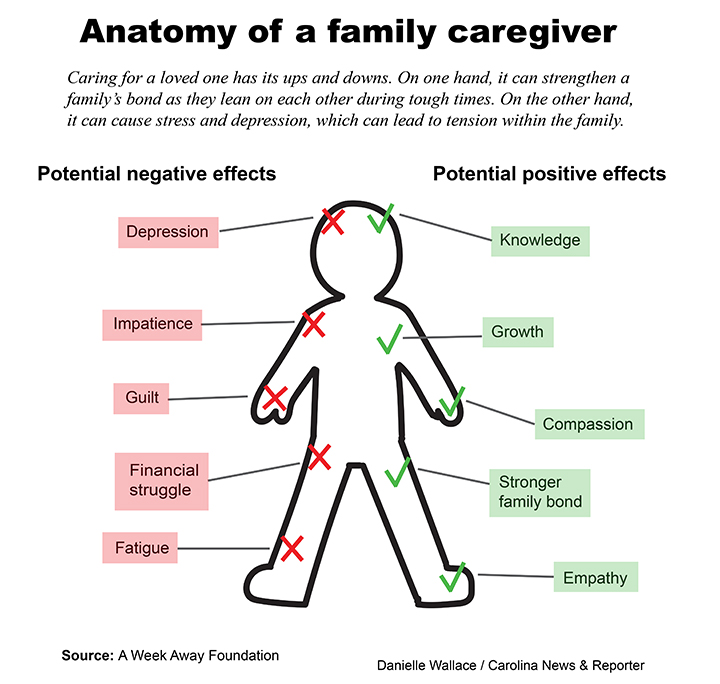

“We want to go visit grandma — we want to help our mom out,” Julia Lako said, referring to the guilt she and her sister feel when they’re not at home. “I think it’s a burden more in the sense of, just, we worry and want to help, but we’re not nearby. But we also know that college is so demanding, so we sometimes can’t go see her all the time, or we can’t do as much to help.”

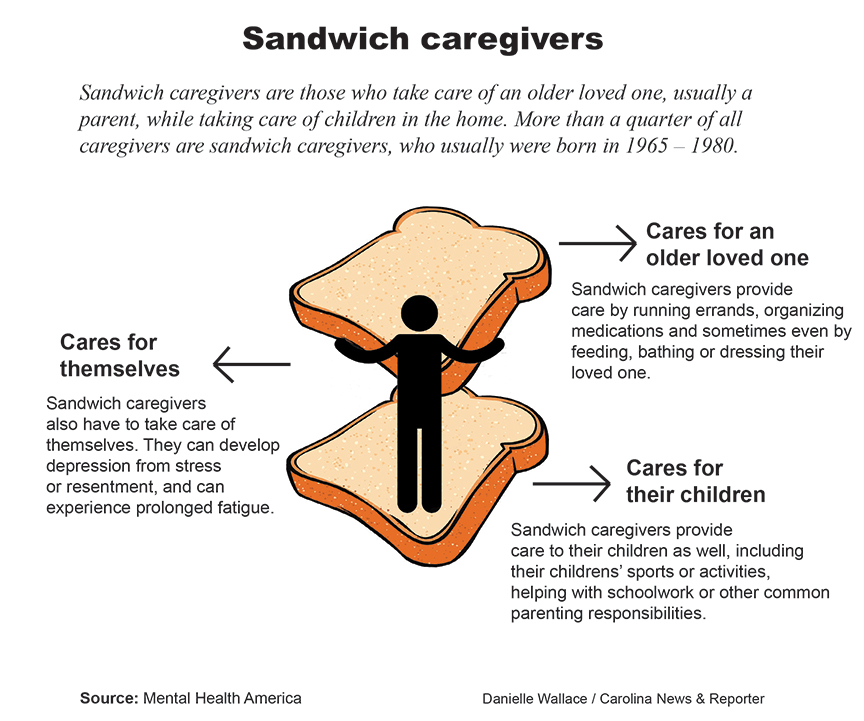

But the sisters don’t just feel the need to visit their grandmother. They also care for their mother, who was diagnosed with lupus in 2010.

Christina Lako suffers from joint pain, swelling and fatigue. She also has Raynaud’s disease, which causes a lack of circulation in her fingers. The conditions make it hard for her to care for her mother, increasing the need for the sisters to step in.

“Picking up, give or take, a 100-pound person, that’s still a lot — especially when your joints can barely hold yourself up,” Sydney Lako said of her mother’s ability to help. “So I think, just, more like from a physical aspect, that’s where (caregiving) takes the biggest toll on (mom’s) disease.”

The Lako family’s situation is known as “sandwich caregiving.”

A sandwich caregiver is someone caring for an older adult and their own children at the same time, such as Sydney and Julia Lako’s mom.

The Lako sisters said they aren’t the “party” type, but their social lives as college students are affected by their new caregiving roles.

“It just alters your life in terms of … you can’t go anywhere, you know, for long periods of time,” Sydney Lako said. “We can’t make plans for weekends because we’re going home, and we’re taking care of grandma.”

While young family members are increasingly taking on caregiving roles, the trend toward younger caregivers is also found in the industry as a whole.

CLIENT CAREGIVERS

Mabry Parrott is 19.

She said being a young caregiver for clients through her parents’ company, RetireEase Senior Services, has created awkward confrontations.

“Being young, it’s a different world, because they all think you’re their daughter, or they think that you’re the affair that their husband had,” Parrott said. “I’ve had a few clients think that I was the … mistress, and they didn’t like me. And I couldn’t go back to their house because they couldn’t realize that I was a caregiver and not the mistress.”

Even if a client is aware that Parrott is their caregiver, her age still causes problems.

“It’s challenging being younger because they almost, they don’t look down on you, but it’s like, ‘You look 12 to me,’ you know?” Parrot said. “It’s almost (like) looking at a middle schooler and being like, ‘You’re going to tell me what I’m wearing today?’”

Parrott said her parents started their company two months after she was born, so she has grown up hearing about the business. She said when she was younger, she was sick of constantly hearing about the company. But now, she can’t get enough of caregiving — at both her parents’ business and at another organization, Leeza’s Care Connection, where she also works.

Leeza’s Care Connection was started by Leeza Gibbons, an Irmo native and a national TV journalist, speaker and author. The organization provides resources and support for caregivers.

Marti Colucci is the organization’s managing director. She has seen an increase in younger caregivers, which she said is due in part to COVID-19 and to the rising cost of medical caregiving.

“A lot of people are working from home because of COVID,” she said. “I also think that our healthcare system in general, for placement of loved ones, is so expensive that people can’t afford it.”

Assisted living facilities and resources in South Carolina cost an average of $3,612 per month, according to a 2021 survey from Genworth, a resource company for long-term care. A home care aide costs roughly $22 an hour in South Carolina, with an eight-hour shift costing around $172, according to Senior Living, a resource for senior housing options.

For caregivers in their 20s or 30s, committing time to a job, a social life and caring for a loved one is difficult to balance.

“You can’t say, ‘Well, I’ve got to quit my job and care for mom full-time because, how am I going to pay my bills?’” Holloway said. “’How am I going to take care of my child,’ you know? … And I don’t think we figured (it) out. … What are we going to do for these younger caregivers?”

Reaching younger audiences, whether they’re caregivers yet or not, could help the industry and seniors in the long run, several said.

Kari Heffron is the home care coordinator for Senior Resources. She said the Columbia organization is seeing an increase in young caregivers and is creating new education outreach programs to present at local high schools and universities.

The Lako sisters said their family is informal, and making jokes about the situation eases the stress.

“This woman will probably be here by the time I’m having grandkids,” Sydney Lako said, jokingly. “Do you know how many times we’ve been like, ‘Grandma’s going to die in the next few months?’ Five years later, she’s still here. … (Grandma) always says, ‘God only takes the good ones,’ and that’s why (her husband) and her son died before her.”

Sisters and USC students Julia Lako, left, and Sydney, far right, help care for their grandmother and their mother, Christina, who has lupus. (Photo courtesy of Sydney Lako)

Sydney Lako and her family often visit her grandmother, Diana, whenever she stays at a respite care facility. (Photo courtesy of Sydney Lako)

Leeza’s Care Connection was founded by Irmo native and TV journalist Leeza Gibbons. It’s located at 201 St. Andrews Road in Columbia, South Carolina. (Photo by Danielle Wallace)

Mabry Parrott, 19, is the outreach coordinator at Leeza’s Care Connection. She’s also a caregiver for clients through her parents’ company, RetireEase Senior Services. (Photo by Danielle Wallace)

Marti Colucci is the managing director at Leeza’s Care Connection, which offers resources, guidance and support for caregivers. (Photo by Danielle Wallace)