Dyneitra Benjamin, a mother of five, lives in rural Orangeburg County. The county has five OB-GYNs — four share the same parking lot. (Photos by Noah Watson)

Dyneitra Benjamin lives in rural Orangeburg County. She started having kids nine years ago and now has five — the youngest born just three months ago.

She’s a single mother with a more than 20-minute drive to the closest women’s health provider. And she’s one of many women in South Carolina who struggle to receive care during pregnancy.

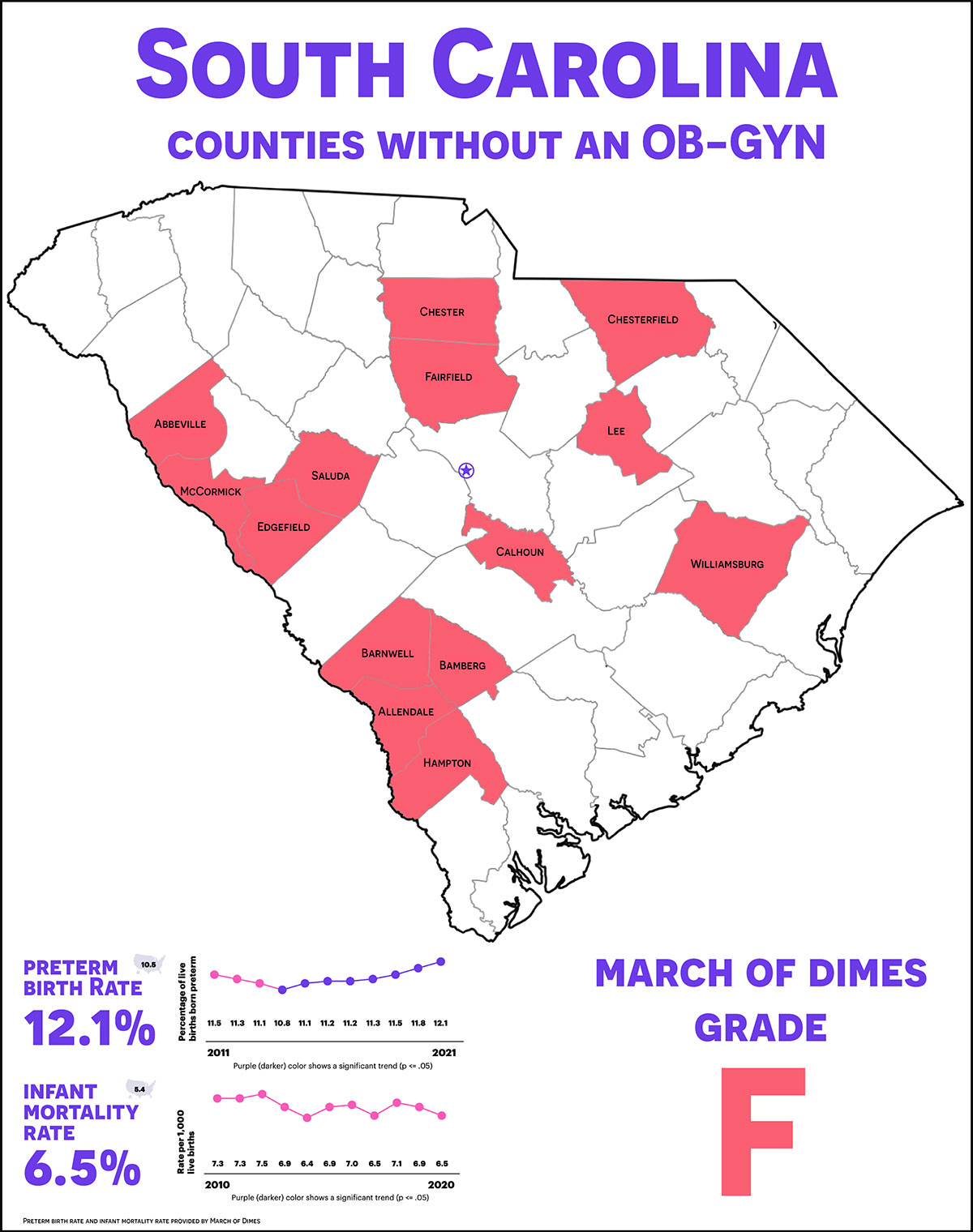

The state ranked 45th in the nation for its care of pregnant women on the 2022 March of Dimes Report Card, receiving an “F” grade. The report card is an annual review that showcases the nation’s state of maternal and infant health.

It compiles statistics such as rates of preterm births, infant mortalities, low-risk C-sections and the percentage of pregnant women who received inadequate care in each state.

Some critics say it’s not that South Carolina is simply bad, but that it’s getting worse.

“South Carolina is just deteriorating in terms of health, especially for women,” said Sharon Bond, a staff midwife in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Medical University of South Carolina. “It’s a national disgrace.”

The latest news comes after a 2021 report from the S.C. Office for Healthcare Workforce concluding that a third of South Carolina counties do not have a practicing obstetrician-gynecologist, a doctor who cares for pregnant women and helps deliver their babies.

The counties are called “care deserts” — areas that lack a specific medical service entirely. All of them are rural.

South Carolina has struggled to provide healthcare in rural counties for decades, said Kevin Bennett, director at the Center for Rural and Primary Healthcare. Fewer than 13% of all physicians in the state are located in rural areas.

Bennett said the problem stems from the way physicians are paid.

Volume-based compensation was the most common type of base pay for doctors between November 2017 and July 2019 according to a JAMA published study.

Volume-based compensation means physicians make a small amount of money per patient visit, so the more patients they see, the more profit they make.

The study concluded that more than 80% of primary-care doctors and more than 90% of specialists at medical practices were payed on volume.

The profit model works for providers who see a lot of patients, Bennett said. In rural hospitals, OB-GYNs suffer.

“Birth rates and the number of pregnant women in some (rural) communities is just relatively low,” he said. “You might have 20 deliveries in a year. How do you make a living if you’re only getting reimbursed per visit?”

And he said a large percentage of hospitals in rural areas cut their OB-GYN services to save money.

The absence of women’s health providers in some areas is taking its toll on women, according to Lamikka Samuel. She is the director of Family Solutions, a non-profit that sends nurses on home visits to low-income new moms in rural areas.

“With the shortage of OB providers, things are just getting harder for women who are finding themselves pregnant in rural South Carolina,” Samuel said.

The March of Dimes report card concluded that 18% of women in South Carolina attended half or less of their prenatal care appointments. The appointments are designed to ensure the health of the baby and the mother.

The appointments are the biggest driver of positive outcomes for pregnancy, Bennett said.

“You have adequate prenatal care, outcomes are great,” he said.

Missing prenatal care appointments is an issue for women in rural areas, according to Rhonda Johnson, a certified midwife in South Carolina.

She said she has seen women travel more than an hour to see a doctor.

“Let’s say there’s a federally qualified health care clinic that’s 30 minutes away,” Johnson said, describing what going to an appointment can look like for rural women. “Well, the federally qualified health care clinic doesn’t do births, so then (the mothers) have to go to a regional area.”

That can be up to another hour drive on top of the clinic visit, she said. Once there, more difficulties can pop up.

“When she walks in the door, those (doctors and nurses) don’t know her, and she doesn’t know them,” she said. “It’s hard to go to a stranger and explain your entire story again.”

Ultimately, Johnson explained, a pregnant woman may have to drive an hour and half going to multiple offices, detailing her medical history four or five times.

For Dyneitra Benjamin, the 20-minute commute wasn’t the hardest part of her pregnancies, it was finding someone to look after her children while she went to the appointments.

She said if she couldn’t find childcare, she would have to miss the appointment. When she asked people to watch her children, she would usually be told no.

“When you are being told no for so long, you choose just not to ask,” Benjamin said. “That kind of shuns you where you don’t want to ask nobody for anything. You just want to do it on your own. That can be overwhelming.”

She struggled with asking for help in her first few pregnancies. As she grew as a mother, she said she started asking for help, regardless of a yes or no answer.

“That’s when I could breathe,” she said.

For the birth of her 4-month-old, she said she built a support system that made finding childcare easier.

“I’m in a whole different space now,” she said. “I have a church family, all my kids have godparents, … so I was able to get to my appointments.”

Her message to other mothers in rural areas: “Keep going. Just find a support system, find somebody or find some people that will light your way.”

Benjamin said having a support system helped her have a successful pregnancy with her most recent child.

Latasha King works for Family Solutions and makes home visits to assist pregnant women and new mothers with health and family planning.

King, a case manager, sees multiple patients for Family Solutions. The organization assists women in Allendale, Bamberg, Barnwell, Calhoun, Hampton and Orangeburg counties.