Venus flytraps are one of South Carolina’s many rare plants. (Photos and graphics by Hanah Watts)

Drive along the relatively new International Drive in Horry County and you will find large tracts of undeveloped land, seemingly rare for a county where development is spurred by the tourism boom of nearby Myrtle Beach.

As you make your way to the gimmicky attractions and overcrowded stretches of sand, an inconspicuous black sign appears to the left, proclaiming the presence of “Lewis Ocean Bay Heritage Preserve.” Behind it lies little more than a narrow patch of dirt masquerading as a parking lot. The only other indication of the preserve’s availability is a wooden bulletin board with maps, rules, and general information about the preserve. To an outsider, Lewis Ocean Bay appears to be little more than a handful of dirt roads winding through a forest alongside a busy road. But that unassuming façade hides one of South Carolina’s biggest kept secrets – the Venus flytrap.

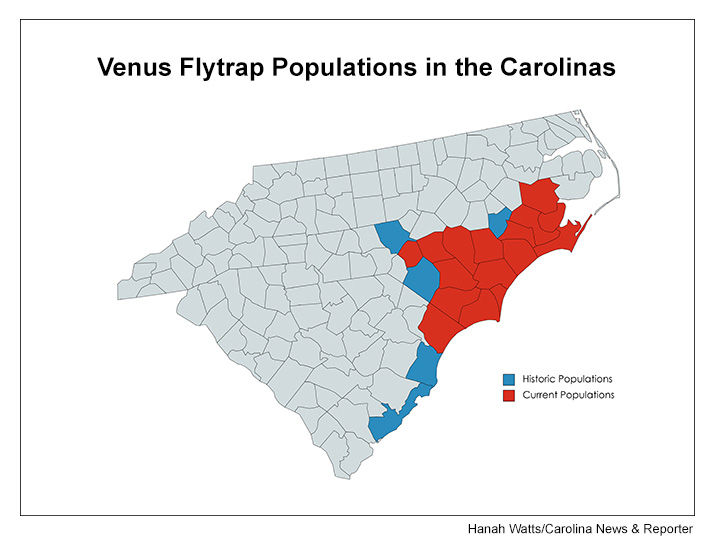

The Venus flytrap — of myth and legend — is native only to North and South Carolina. The flesh-eating plant’s origins are found in 18 counties in North Carolina and three in South Carolina. It grows in the swampy wetlands and longleaf pine forests surrounding the mysteriously formed Carolina Bays.

While the plant is famous around the world, it faces a problem at home. Due to development and habitat loss, the Venus flytrap is looking to join the federal endangered species list under the Endangered Species Act.

BIOLOGY AND DIET

For some, learning the plant comes from our state is surprising.

“Most people’s ideas about a Venus flytrap stem from (the movie and musical) ‘Little Shop of Horrors’ and alien plants that eat people and animals,” said John Hutchens of Coastal Carolina University, who researches the plant. “People just have this sense of an exotic plant. It eats animals, and it must be strange because there’s movies and plays about it, so it must live somewhere very far away.”

The unique mechanisms and carnivorous nature of the plant lead people to believe that it’s an exotic organism found in the jungle, said James Luken of Coastal Carolina University, former colleague of Hutchens who also has studied it.

“I’d say it was a Hollywood thing, you know?” said Herrick Brown, curator of the University of South Carolina’s A.C. Moore Herbarium.

The name “Venus flytrap,” along with its scientific name Dionaea muscipula, comes from the mythos of ancient Greek and Rome. Both the scientific name and the common name confuse experts, though they agree it originates from the Roman goddess of love and beauty — Venus. But 18th-century naturalists were not raving about the plant’s majesty. Instead, they named it after Venus because the trap portion of the plant resembles a specific part of the female anatomy.

A more “PG” explanation suggests that, like the goddess Venus luring men with her feminine wiles, the plant lures flies into its reddish maw to devour them for lunch.

The plant evolved to capture living prey due to the nutrient deficient soil of its native habitat. In Horry County’s Lewis Ocean Bay – one of the last places they can be found in South Carolina – the flytraps live in nitrogen-deficient, sandy soil, with a water table so high that its roots are constantly submerged.

While Hollywood and Broadway portray the plant as willing to consume anything within reach, including human flesh, the plant is quite small, and has a diet largely devoid of flies.

“Ants and spiders, spiders and ants,” Hutchens said.

The flytraps catch their creepy-crawly prey in what Brown calls a “very specialized leaf.”

These “specialized leaves” have a unique ability on par with an average kindergartener – they can count.

Each leaf — the plant has from four to eight on average — has three trigger hairs that act as its prey detection.

If a trigger hair is touched once, nothing happens. But if two hairs are touched simultaneously or if one hair is touched twice in rapid succession, the plant pushes water into each half of the trap – snapping closed.

“It’s like double clicking on a mouse,” Brown said.

This counting mechanism is important for the plant, Brown explained. It takes a large amount of energy for the plant to close, so any misfires can be risky.

When the trap closes, it forms a seal around its dinner. Once the flytrap is done digesting – usually a week or two later – the leaf springs back open, and the carcass of its meal floats to the ground.

Hutchens and his team worked with Luken on a project to learn more about the mysterious carnivores in Lewis Ocean Bay. While Luken focused more on the plant itself, Hutchens’ team focused on the diet of the plants, taking leaf samples to analyze the prey found within.

“It was really interesting to me to find that they actually eat very few flies, or in other words, very few animals with wings,” Hutchens said. “The majority of their diet is ants and spiders that just crawl around and end up on a plant. They walk around on a leaf and that leaf closes around them and eats them.”

The largest meal that his team found in a trap was a millipede – over an inch long. Even though the bug was larger than the trap, it was curled up in a way that the plant could easily close around it.

“In general most (of the bugs eaten by the Venus Flytraps) were – at best – about half the size of the leaves.” Hutchens said.

THE VENUS FLYTRAP PROBLEM

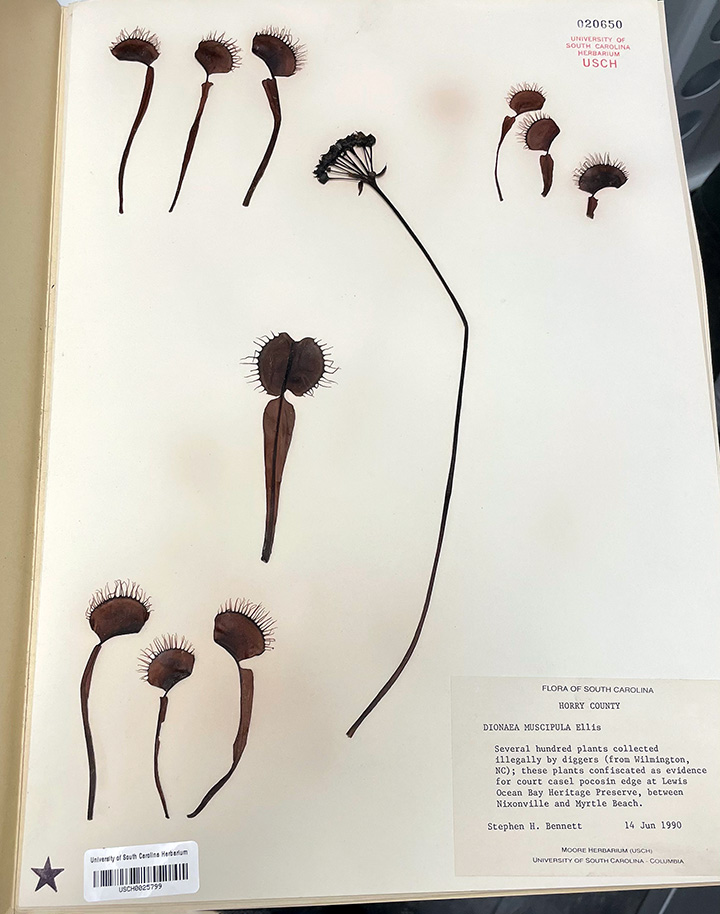

While Venus flytraps are commercially prosperous plants, their populations are dwindling in their natural habitats. In North Carolina, it is a federal offense to poach Venus flytraps. In South Carolina, it is a misdemeanor.

The South Carolina Heritage Trust was created in 1976 to slow habitat loss and protect culturally significant places. The South Carolina Department of Natural Resources manages 76 heritage preserves totaling more than 83,000 acres of land.

“These natural areas and cultural sites provide resources for scientific research,” according to DNR’s website. (They also) “serve as reservoirs of natural and historical elements and habitats for rare and vanishing species.”

For Lewis Ocean Bay Heritage Preserve in Horry County, “rare and vanishing species” is one of its strong points.

Lewis Ocean Bay has more rare plant species than any other heritage preserve in the state, according to DNR’s botanist Keith Bradley.

“We’ve got about 3,000 native plant species in this state, and over 700 of those we track as rare species,” Bradley said. “We maintain a database of their locations as best as we can. We’re actively walking around the woods trying to find them and map them.”

Venus flytraps are on that list.

Lewis Ocean Bay features rare plants such as pogonia orchid, white-fringed orchid, pine lily and green pitcher plant. It houses the threatened red-cockaded woodpecker and the largest black-bear population in South Carolina, according to the Audubon Society.

The preserve is also one of the last publicly accessible places in South Carolina where Venus flytraps are found.

Bradly and his team keep track of the Venus flytrap populations in the preserve as well as maintain the habitat. One of their biggest struggles is not with the habitat itself but the changes made to the ecosystem due to rapidly encroaching development.

When Luken gives seminars and speeches about the Venus flytraps, he likes to cite a paper published in 1958. According to Luken, the report documents large populations of the plant across eastern North Carolina and northeastern South Carolina.

Luken chuckled as he remembered the next line, “and we’re pretty sure they’re safe because there is never going to be any large-scale development in this part of the Carolinas.”

This part of South Carolina includes Myrtle Beach, which was the third-fastest growing metro area in America last year, according to the U.S. census.

“It used to be primarily just a tourist attraction where people would come to the beach.” said Luken. “But within the last 10 or 15 years it’s becoming a very popular retirement destination, so there’s huge amounts of development occurring everywhere.”

ISSUES FACING PRESERVATION AND THE ENDANGERED LISTING

Because Venus flytraps are found in longleaf pine forests with dense vegetation, that’s an issue for plants like the flytrap that need plenty of sunlight. In nature, fires burn away some of the dense vegetation, allowing for new growth underneath. For Venus flytraps, prescribed burns are essential for survival.

“Lewis Ocean Bay’s flytrap population for now — because of our ability to burn — seems to be relatively stable,” Bradley said.

However, DNR cannot burn close to urban development due to wildfire risks.

“I can tell from the vegetation changes that we have lost Venus flytraps from some part of the preserve because of adjacent developments,” Bradley said.

The Venus flytrap is not the only fire-dependent species in Lewis Ocean Bay. The burns contribute to the richness and diversity of a variety of organisms in the preserve. Even the threatened red-cockaded woodpecker is fire dependent.

But the lack of prescribed burns is not the largest problem facing the plant.

“The most kind of insidious thing about the development is the altered hydrology,” Luken said.

The subdivisions built near Lewis Ocean Bay are draining the swamps.

“Parts of Lewis Ocean Bay, they’re basically drying up,” Bradely said.

Horry County has seen worsening flooding in the past couple of years.

“The more we destroy wetlands, the worse flooding is going to get because it just increases the speed at which water runs off,” Luken said.

In 2016, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service was petitioned to list the Venus flytrap as an endangered species. In 2017, the agency published a 90-day review that updated the flytrap’s status and said the “petition contained substantial information indicating listing may be warranted for the species.” It then began its investigation. Five years later, no decision has been made.

Local biologists and conservationists hope a decision will come in the next couple of years.

So, for now, the flytraps are relatively safe. But their future remains uncertain.

Lewis Ocean Bay is one of South Carolina’s 76 Heritage Preserves.

The typical Hollywood-style representation of a Venus flytrap

Venus flytraps

Preserved Venus flytrap specimens at the USC Herbarium

Each leaf has tiny trigger hairs that aid the plant in catching its prey.

A flytrap that has closed around its prey

Specimen archives at the University of South Carolina Herbarium

Green pitcher plants are another carnivorous plant found in Lewis Ocean Bay.

During hunting season, visitors to Lewis Ocean Bay must wear blaze orange for safety.

A small parking and informational area within the belly of the preserve

Some of the diverse flora at Lewis Ocean Bay

Trees with a band of white paint around the trunk signify the presence of the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker.

A sign telling hikers that the fire breaks may be accessed only by foot

A fire break in Lewis Ocean Bay Heritage Preserve

A densely vegetated path in Lewis Ocean Bay