Groucho’s Deli in Columbia’s Five Points area cleans its dining room during slow times. (Photo by Savannah Nagy/Carolina News and Reporter)

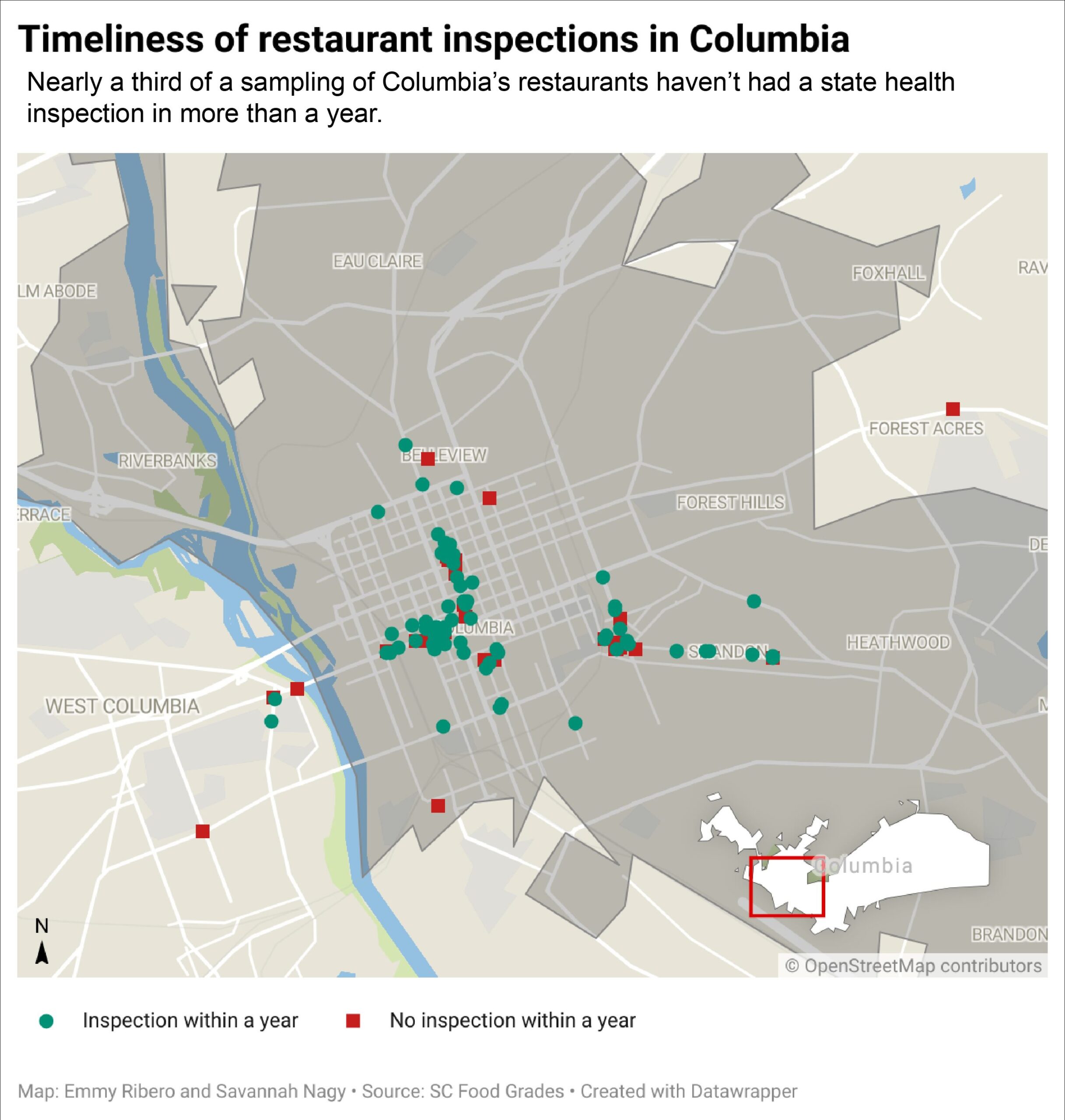

Nearly a third of 100 downtown Columbia restaurants have not been inspected in the past year because of understaffing at the state health department, prompting concerns about food safety.

Restaurants from across the state sampled by the Carolina News and Reporter have good, current grades from the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control. But some have gone long periods without an inspection despite being flagged earlier for concerning conditions.

“I feel like the food industry should be just as regulated as, like, healthcare is,” Elizabeth Elsenbach said while visiting a West Columbia restaurant recently. “There should be set timelines, and if you don’t have enough people, you should hire more.”

State regulations for retail food establishments do not specify a frequency for DHEC inspections. But “routine inspections generally range from one to four times a year,” Casey White, a DHEC spokesperson, said in an email.

Staffing shortages are affecting the frequency of inspections, White said. Restaurants that have shown shortcomings in the past take precedence with inspectors, he said.

“We have experienced staffing shortages statewide since the COVID-19 pandemic,” White said. “We do strive to get to such facilities every year, so we are currently engaged in additional staff hiring as well as providing additional inspection beyond normal working hours and on weekends.”

A sample of 30 food businesses in Charleston found a similar ratio of restaurants as in those sampled in Columbia without DHEC inspections in the past year. In nearby Augusta, Georgia, all restaurants sampled had an inspection in the same period.

In other regions of South Carolina, fewer restaurants had lagging inspections. In downtown Greenville, only 2 of 31 sampled had gone more than a year without an inspection. In Myrtle Beach, four of 30 sampled had not had a DHEC visit in the same period.

Most restaurants aren’t averse to inspections from the agency and would prefer they be frequent.

“Cleanliness is next to godliness,” said Terry Penton, manager of Columbia’s Grill Marks. “They need to be performing the task at hand to ensure that we’re giving a correct food and temperature to the public.”

Grill Marks was inspected in July 2023, posting a grade of “A.”

Many restaurants take food safety seriously, but some may need inspections to stay in line.

Chipotle on Gervais Street received “B” and “C” grades in June 2022, which the food chain corrected three days later, earning an “A” grade.

But the Chipotle location hasn’t been inspected by DHEC since.

White said DHEC considers poor history when deciding how often to conduct inspections. A “C” is the lowest grade possible in DHEC inspections.

The Chipotle location was docked for incorrect food-holding temperatures and a poorly functioning refrigerator door at the main serving line.

Christian McLaren, apprentice manager at the Chipotle, said it has third-party companies perform inspections on a quarterly basis, which the restaurant consistently passes.

He said he’s not sure DHEC is aware of this and thinks they should visit again, regardless.

How it works. What’s expected

DHEC has guidelines for assigning risk categories to restaurants, impacting the frequency of inspections.

The agency ranks food businesses’ risk levels from 1 to 4. Those ranked 4 are considered in need of more frequent inspections.

The category is determined by a combination of how complex the restaurant’s cooking process is and the business’ history with inspections. For example, a restaurant that only warms up pre-cooked food and has a perfect history would be in Category 1.

Of the one-third of the sampled Columbia restaurants that had not been inspected in at least a year as of February, 21 were in Category 3. Three of the restaurants were in Category 1. And eight were in Category 2.

Restaurants must pay the agency an annual fee based on sales. The cost ranges from $100 to $450 annually. If they don’t pay, they can lose their business licenses.

“Normally, whenever you renew your business license, which is yearly, you’re pretty much guaranteed to see DHEC within, like, a one to two-month window,” said Colie Moore, manager at Groucho’s Deli in Five Points.

Moore said it has been just about a year since DHEC last visited that Groucho’s Deli location. DHEC’s database says its last inspection was in August 2022. It has passed every inspection since 2021 with an “A.”

Payton Fair manages the kitchen at The Grand on Columbia’s Main Street and said he has been in the industry for more than 10 years. He said The Grand has not had a DHEC inspection in the year and a half he has worked there.

“Of course I think that’s weird because I’m very used to getting it,” Fair said. “It doesn’t bother me as much for someone who legitimately cares about the food safety, right? But it does give me pause and make me worry about others.”

The Grand has received all “A” ratings on inspections recorded in the database.

Fair said some restaurants take it upon themselves to hire a third-party inspector or sanitation monitor, which he believes they “should not have to do.”

“A lot of companies do a lot of things to make their own health inspections,” Fair said.

Fair said he previously worked at a restaurant in Columbia where a private company conducted an inspection that was more stringent than DHEC’s inspections.

What’s next

State lawmakers have decided to split DHEC into two agencies and move the responsibility for retail food sanitation and safety to the S.C. Department of Agriculture.

“Fifty-five percent of our agency will now be focused towards food safety, as opposed to less than 3% with the department of health,” said Derek Underwood, an assistant commissioner at the agriculture department.

The state law splits DHEC into two organizations: the Department of Public Health and the Department of Environmental Services.

“There’s a significant difference between certifying food quality safety and then certifying like a vaccination facility,” Senator Kimbrell, R- Spartanburg. “And I feel like over the years what happened is there’s just too much-piling everything into one agency that grew into really a monstrosity that was beyond anybody’s control, and just not real efficient.”

Underwood said the split will be better because larger organizations can lead to less productivity.

“The smaller the company, the more focus you can have and the more when things get big,” Underwood said. “Not indicated that that happened with DHEC.”

White said he doesn’t think the move to the agriculture department will disrupt any day-to-day food inspection operations.

“We are working with (agriculture) leadership to ensure that the transition is seamless and that these important services are maintained and, where possible, enhanced as we make this change,” he said.

DHEC employees who work in food safety will become employees of the agriculture department. The agency is planning a more centralized approach to inspections, Underwood said.

Agriculture employees will work from home and inspect the restaurants in their area, rather than driving to work at regional offices, as DHEC employees now do.

That approach, which begins in July, should allow the agency to get more done with fewer people, Underwood said.

A map depiction of the downtown restaurants in Columbia used for the sample.

Jack Brown’s Beer and Burger Joint waits for the evening rush. (Photo by Savannah Nagy/Carolina News and Reporter)

Merchandise for Groucho’s decorates the walls. (Photo by Savannah Nagy/Carolina News and Reporter)

A customer relaxes at Pawley’s Front Porch during a slow time of the day. (Photo by Savannah Nagy/Carolina News and Reporter)