Drivers crossing the Gervais Street bridge might not be aware of the history lying in the river beneath them. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

On a concrete pad in West Columbia’s Riverwalk Park, in the shadow of the Gervais Street bridge, sits an anchor.

An inscription beneath the anchor says it belonged to the “CSN (Confederate States Navy) City of Columbia.” But there’s a problem with that inscription.

“(The ship) was built in 1905,” said Jim Spirek, a state underwater archaeologist at the South Carolina Institute for Archeology and Anthropology.

The City of Columbia never would have served as a Confederate warship, since the war ended 30 years before the ship was built. It’s likely the anchor belonged to another ship that did fight in the war and is erroneously attributed to the Columbia. Another possibility, according to Spirek, is the anchor is indeed Columbia’s, but the letters “CSN” were welded on at a later date.

Whatever the truth, the ship is just one example of the artifacts sitting in the Congaree River. A current project to clean up coal tar from the floor of the river has created renewed interest in what lies at the bottom. And according to archeologists, historians and divers, artifacts in the river range from the prehistoric to the modern day.

While many of the items have been found and preserved, more still might be lying in the river, under the feet of the people living and working in the cities built on either bank. Many of these artifacts, such as the City of Columbia shipwreck, help tell the area’s history.

The Columbia spent the early 1900s carrying passengers and cargo from Columbia to Georgetown to connect the Midlands to larger ships headed for New York. When railroads became cheaper and easier for traveling to the coast, the Columbia was decommissioned, beached and later sank on the Congaree’s west bank sometime in the 1910s, Spirek said.

The wreck can still be seen on West Columbia’s riverwalk, especially at times of low water. A computer error at a dam on the Broad River upstream, compounded with annual summer dry spells, made the remains especially visible in recent months, said Bill Stangler of the Congaree Riverkeeper environmental organization.

COAL TAR CLEANUP

Directly across the river from the wreck of the Columbia, near the site where it was built in 1905, a temporary levee was built this summer at the base of Senate Street. It’s part of a cleanup of industrial runoff from the riverbed.

The cleanup project is a joint venture between Dominion Energy and the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control as well as other local entities, according to DHEC’s website.

Preliminary work for the project began in 2010, but the actual removal of the coal tar is expected to begin next spring, said Greg Cassidy, DHEC’s manager for the project. Another cleanup on a smaller part of the river just downstream will begin after this one is completed, he said.

The water inside the levee is being pumped out to expose the riverbed and allow workers to remove coal tar left by industrial runoff during the first half of the 20th century, Cassidy said.

The tar has not significantly affected aquatic wildlife, he said. But it will cause irritation if it makes contact with human skin. The idea is to keep the tar from coming into contact with the river’s recreational users.

CIVIL WAR EXPLOSIVES

But coal tar isn’t the only potentially dangerous material lurking underneath the water’s surface.

During the occupation of Columbia in 1865, the Union army dumped much of the city’s Confederate armory into the river where the cleanup is now taking place. The project will potentially have 150-year-old explosives to deal with, Cassidy said.

While many of the artifacts are believed to have been removed years ago, the munitions could include unexploded ordnance from the war.

The coal tar will go to a landfill, Cassidy said. Any ordnance will be handled by specialized workers based on how dangerous it is. It may be destroyed if it is explosive. But anything not potentially harmful will be salvaged and preserved.

What they find is unlikely to explode, W.C. Smith of the Palmetto State History Foundation Board said. Civil War-era explosives have to be set and detonated by a lit fuse and will not explode on contact, he said.

The DHEC project is the third time the area has been dug up. The first was an informal dig in the 1930s when the river was low, Smith said. The second time was in the ’80s, when Smith and a team of explorers borrowed some equipment and went digging themselves.

Smith said his team didn’t find as much as they had hoped, in part because the group in the ’30s got there first. Additionally, he said, unlicensed poachers dove in the area at night while he was working with his team in the 1980s.

Nevertheless, “there’s a lot of bullets,” Smith said. “When we were in there with the dredges, we had bullets flying out the dredge.”

It was common for Confederate arsenals to be dumped in rivers in cities across the South, he said. But one type of bullet, with a signature ring-tail design at the base, has only been found in the Congaree River.

Smith said the unique bullets may have been manufactured at the end of the war and didn’t have a chance to be shipped to the front lines before the city fell.

Smith thinks the current project might be more successful than his attempt in the ’80s, because DHEC is digging up dirt that was dumped on top of the original riverbank in the 1970s. The dumping project covered the coal tar as well as much of the riverbed where some of the arsenals may have been dumped. His group couldn’t do any digging there because its archeology institute permits at the time wouldn’t allow it, Smith said.

So is there anything left for them to find?

“This should … really, with the removal that’s being done, really answer that question in a way that’s never been done before,” Cassidy said.

Perhaps even “once and for all,” he said.

Smith still has most of what his group found in the ’80s and plans someday to donate the collection – including shells and small arms ammunition – to the S.C. Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum, he said. The material dug up in the ’30s was scattered to private collectors and not preserved, he said.

The museum doesn’t have much from the Congaree, said Chelsea Sigourney, the museum’s Curator of Exhibits and Collections. She said she’s interested to see how any new findings might match up with the museum’s records of what was in Columbia’s armory at the time.

“I’m super curious about that,” Sigourney said. “And then, yeah, just a better understanding of what the Confederacy was using and what the Union wouldn’t have wanted.”

The Union would have thrown out captured Confederate materials they didn’t want to carry as they continued marching, including some of the more rag-tag, outdated equipment the Confederacy was using, Smith said. Some of it was British — whether loaned directly to the Confederacy or left over from previous wars, such as the Mexican-American War and War of 1812.

“It was antiquated guns, so the federals didn’t need it,” Smith said. “But (the Confederates) were using it because we needed what we could get our hands on.”

MORE THAN JUST THE CIVIL WAR

Items from other eras of the city’s history might also be under the water.

A ferry crossing existed at the end of Senate Street for centuries. People continued to use it even after the Gervais Street bridge opened next to the landing in 1928, Smith said. The ferry landing and the roads leading to it made the spot accessible for Sherman’s Army when it dumped the captured weapons in 1865, he said.

Several bottle dispensaries were previously located in the area, so glass bottles tossed into the river over the years also could be in the surrounding waters, Smith said.

“That little spot right there has been a hot spot at the end of Senate Street for people coming and going for the last 250 years,” Smith said. “There’s more in there than just the ordnance. The potential of all eras is in there.”

The archeology institute’s records of artifacts from the river include prehistoric pottery; bullets, cannonballs and other projectiles of various caliber; Coca-Cola, medicine and perfume bottles from the 1900s; and bricks, fishing equipment and modern garbage, an underwater archeologist with the institute, William Nassif, said.

Native American and prehistoric artifacts are common finds in the Congaree. Downstream in Cayce at the 12,000 Year History Park, past residents of the area, from mammoths to Native Americans, have left behind historic items.

Little is known about the Congaree people who lived in the area and gave the river its name. Many of them were killed by diseases introduced by European colonists, leaving the survivors to be absorbed by other tribes, according to the National Park Service.

Robert Benfield, a local licensed diver, has found Native American pottery, glass bottles from the 1800s, pipe stems, pieces of metal and “a lot of trash” in the river, he said.

Among the trash?

Tires, stoves, and refrigerators of various ages, Stangler said.

A HIDDEN GEM FOR DIVERS

The Midlands’ Congaree and Saluda rivers “are both gems that no one ever dives,” Benfield said.

“I think if divers really hit those areas, there’s a lot of stuff undiscovered that could come to the surface,” he said.

The number of divers with the equipment and skill to dive for artifacts is small and close knit, he said. He’s planning on bringing friends to dive in the area of the coal tar cleanup as soon as the project is over.

“Any piece of history you can find, no matter how old it is, it’s kind of like Christmas time,” Benfield said. “It’s something new that no one’s seen in a long time … It’s just a fascinating feeling. You’re kind of reliving history through someone else’s eyes.”

A diver seeking treasures needs a license from the archaeology institute, Spirek said. They cost $5 for six months and $18 for two years, according to the institute’s website.

The divers also must report any artifacts found. The institute then has 60 days to test and catalog findings before returning them to the diver. Spirek said people bring in items from the Congaree almost monthly.

Treasure hunters should know that items found by unlicensed divers may be confiscated. Two 300-pound bronze propellers that were recently pulled out of the river by a local man’s pickup now sit in the Cayce Museum and at the archaeology institute’s office, for example.

Spirek said the Cooper River in Charleston is a much more popular diving site.

Benfield said he has found megalodon shark teeth and other fossils during hundreds of dives in the Cooper River near Moncks Corner. He also has made dives in Lake Murray, where there are underwater towns left on the bottom during the lake’s creation in the 1920s to provide the Midlands with hydroelectricity.

“I don’t think enough people dive on the Congaree,” Benfield said. “I would encourage more people to dive it. I think there’s a great opportunity you’ve got here.”

The Congaree has better visibility for diving than the Cooper River, Benfield said. But the rocky, shallow areas around downtown Columbia make it difficult to get to places where artifacts might be. And the the shallow nature and rapids of the Congaree make it difficult for large pieces of historical artifacts to be preserved, Spirek said.

“There’s not too much surviving because the river is quite forceful — it’s moving things around and burying things as well,” Spirek said.

The Congaree is only around 5 feet to 10 feet deep in the downtown area, Spirek said. So many smaller artifacts are right there at the surface.

“We have people just go walking on sandbars and finding prehistoric pottery and ceramics,” he said.

Stangler said you can easily dig around on a sandbar in the Congaree and find anything from Native American and Colonial pottery to ’80s pop-top beer cans.

“Rivers are certainly places where people have congregated for hundreds, sometimes thousands of years,” Stangler said. “Rivers have been and are still now meeting places, where people come together. And I’ve always found that interesting.”

An anchor on display in West Columbia’s Riverwalk Park is purported to be from the Confederate warship City of Columbia. But that inscription is inaccurate, state Underwater Archeologist Jim Spirek said. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

The City of Columbia steamship was built in 1905 and couldn’t have served as a Confederate warship, despite what the plaque underneath it and the welded “CSN” label on the anchor say, Spirek said. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

The wreck of the City of Columbia steamship is still visible on the West Columbia side of the Congaree River bank, where it was beached and sank sometime in the 1910s. The wreck is accessible at low water via a trail branching off from the walking path in West Columbia’s Riverwalk Park. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

The City of Columbia before it wrecked. The boat had two decks and a paddle wheel at the stern to propel it through the shallow river water between Columbia and Georgetown. (Photo courtesy of the S.C. Institute for Archeology and Anthropology)

A view from the Gervais Street bridge of the Dominion Energy and S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control Congaree River cleanup site. The area inside the white coffer dam is being pumped dry to expose the riverbed for the removal of coal tar dumped into the river by factories in the mid-20th century. Columbia’s Confederate armory also was dumped into the area when the Union Army occupied Columbia in 1865. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

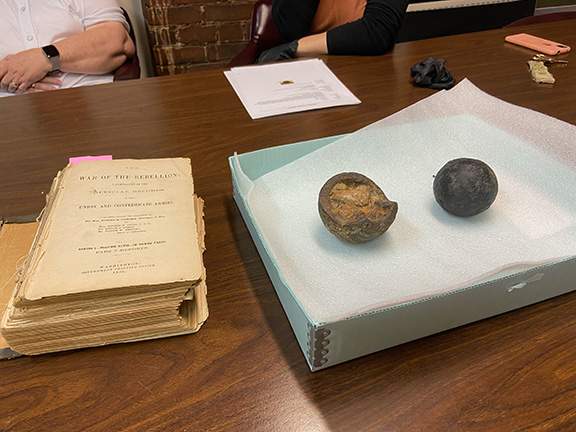

The S.C. Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum has shells recovered from the river from both the Civil and Revolutionary wars. The book pictured is an original print of an 1895 record of the contents of various Confederate armories, including the one in Columbia. Museum curator Chelsea Sigourney is hoping artifacts recovered by the current river cleanup project will verify the accuracy of these records. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

A collection of shells and projectiles recovered from the Congaree River in the area of the current cleanup project during dives in the 1980s. (Photo courtesy of W.C. Smith III)