Teachers are feeling pressure in multiple areas as they transition back into in-person learning. Photos by Julie Crosby

Teachers aren’t speaking up for themselves in a time of extra stress and additional classroom obligations, the president of the South Carolina Education Association said this week. Sherry East lays the blame on a “culture of fear” and intimidation tactics.

“[Teachers are] scared to death of their administrators. They are scared of getting in trouble,” East said.

The coronavirus pandemic added an unprecedented layer of stress on American teachers, as the 2020 lockdown forced teachers to go online and develop resources to reach students who did not have access or were struggling to adapt to the new technology. Now that most are back in the classroom, they have to work to reclaim some of the academic ground lost during COVID-19.

According to East, she has received emails from teachers detailing instances of school districts using surprise evaluations in an attempt to quell teacher complaints. She declined to say which districts or administrators were named in the emails, citing teacher privacy.

“Why would you speak up if you thought your school board member was going to show up at your school and observe you for the day? That would quiet you down a lot,” East said.

A shortage of teachers in South Carolina has placed additional pressure on educators and administration, including challenges faced by minority teachers, who are already under-represented in the classroom.

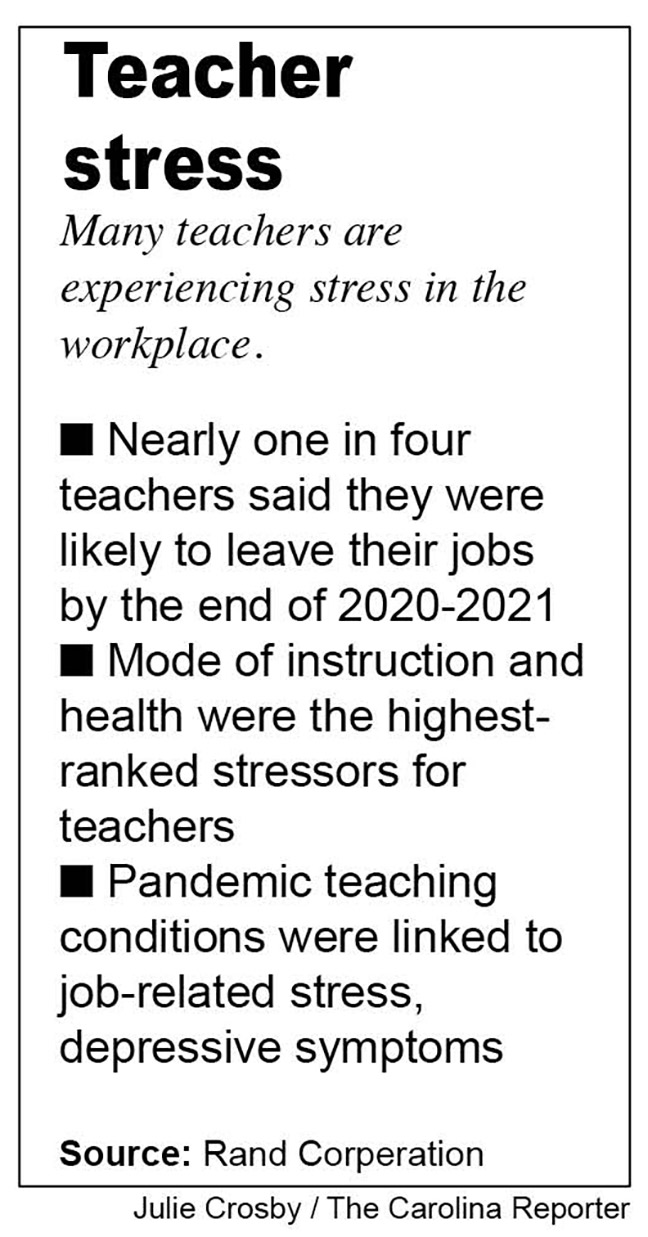

Thirty-six percent of first-year K-12 South Carolina teachers hired for the 2019-20 school year did not return to a teaching/service position in the same district in 2020-21, according to the Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention, and Advancement.

The Center, which is located at Winthrop University, aims to recruit, retain, and advance S.C. educators.

Across the country, 8% of teachers leave their careers annually and more than 50% of educators quit before reaching retirement, according to the National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Lisa Ellis, founder of SC for ED, an organization that helps teachers advocate for themselves and their students, said teachers have nothing to fear when they decide to speak up for themselves.

“They’re not going to fire you because there is no one to replace you. There’s no one,” Ellis, who teaches journalism at Blythewood High School, said.

S.C. is ranked 41st among the 50 states in teacher satisfaction, a drop from the 2020 ranking at number 40.

Ellis said some teachers are not able to escape the fixed mindset that has kept the predominantly female profession quiet for so long.

“It’s still that mentality of, ‘Well I’m just grateful to be here’ or ‘I could never ruffle any feathers,’” Ellis said. “So they continue to be just really taken advantage of, and I think administrators and school boards and district office people manifest that culture of fear.”

For some teachers, speaking with administrators or their school board poses too much of a risk.

“There’s all kinds of reasons they’re not speaking, and it’s almost to the point with this association that there are grievances out there and the law is being broken,” East said. “And I cannot get teachers that will put their name on the line to fix it because they’re so afraid.”

While teachers all over the United States are struggling with issues, South Carolina teachers also contend with low pay and retention issues, said Kaneale Cornell, a director for the South Carolina Education Association.

Cornell was an educator in Ohio before she moved to South Carolina for her job with the SCEA. She said there are noticeable differences in teacher experiences between the two states.

“Teachers here don’t have all the same wonderful opportunities of planning, collaborating, learning more and having those choices. So, they don’t get planning time; they don’t get lunchtime if they needed to take a mental break. They don’t get it,” said Cornell.

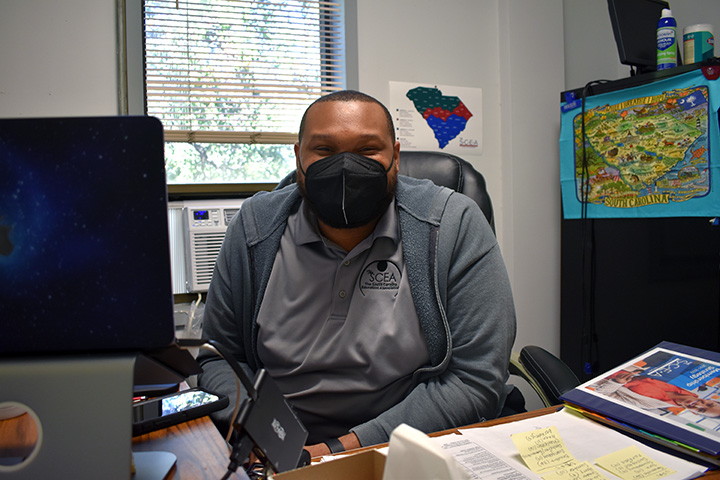

Albert Jones III, the membership and leadership development specialist for the SCEA, said he left his position as a fourth grade teacher in Lexington-Richland School District 5 to be able to advocate for change.

“I didn’t leave under distress or craziness, but I think for me, on this side, I know it was a matter that I could make a bigger impact,” Jones said.

In the classroom, “you feel as if you have to watch what you say and watch what you do, be very careful with opinions or be very careful with anything of that nature. I really have the ability to advocate and really push that forward.”

Ellis said sometimes people can misinterpret what an administrator says to them as “construed as intimidation but actually isn’t.”

Frank Morgan, retired superintendent of Kershaw County School District, said that collective stressors may have something to do with apprehension among teachers.

“Certainly that’s not something as an administrator that I would have ever tolerated and most superintendents would say the same thing,” Morgan said. “I think what you’re hearing is just indicative of the boiling cauldron of stress that everybody is working under.”

Michael Burgess, lead teacher for the Center of Law and Global Policy Development at River Bluff High School, said his school administration values the suggestions he has brought to the table.

“I’m sure they don’t like everything I’ve said or proposed or argued for, but at the same time I think they also recognize that I’ a professional and I’m going to have some different views. As long as those views are presented respectfully, while they might disagree with it, they honor the a professional is able to express themselves,” Burgess said.

He said this type of support in the classroom is dependent on a school district’s willingness to listen.

“My situation is a lot different than some of the teachers in some of the other school districts,” Burgess said. “The majority of these places [schools], they literally don’t want to hear teachers speaking out and will do certain things to squash it.”

Morgan, the retired superintendent, also noted that while he had seen instances of teacher intimidation over his time as superintendent, they were not typical. He also said that support from school district officials is important for teachers to feel more support.

“I think it’s really contingent on upper leadership in the school district and political leadership now to be visible, to be really goof listeners and to try to turn what they’re hearing into action to support people on the front lines,” Morgan said.

Sherry East, president of the South Carolina Education Association, noted that many teachers are on anxiety medication or have health issues from the stress of their job.

Stress due to COVID-19 and on-line teaching have caused educators to feel extra pressure in their careers.

Albert Jones III, membership and leadership development specialist for the SCEA, said there is extra pressure placed on African American male teachers, one of the most under-represented groups of teachers in schools.

Signs, such as this one, highlight the passionate mindset many teachers have when beginning their career.