Jay Matheson has been involved in Columbia’s music scene since the early 1980s as both a musician and audio engineer. Photos by: Trey Martin

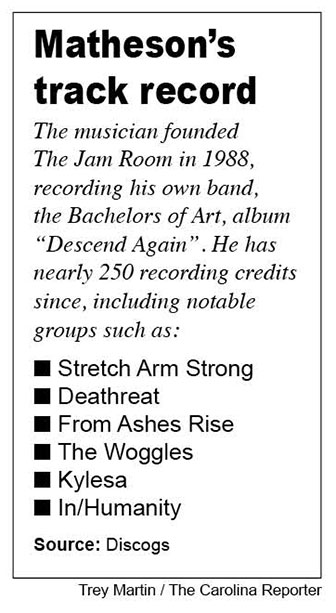

A seasoned musician and self-taught audio guru, Jay Matheson and his studio, The Jam Room, have crafted the sound of Columbia hardcore music for nearly four decades.

“My band opened some shows for Slayer in town on their very first nationwide tour, and now they’re retiring, so that’s how long I’ve been at it, long enough for one of these bands to start and retire,” said Matheson.

Matheson grew up in the small town of Wagener, South Carolina, but traveled to Columbia frequently, attending his first concerts and purchasing his first guitar in the city.

Eventually, as Matheson would say, heavy metal music finds you. At a time when radio play was extremely limited and long before the days of streaming music over the internet, he discovered new music by word of mouth. When a friend played him Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid” album, he instantly fell in love with the metal scene.

“We actually had a Black Sabbath tribute band for many years, so they were kind of my core band. It was heavy, dark sounding stuff and people from the subculture really gravitated to it,” said Matheson.

Learning his skills

Music venues did not have their own sound system, so Matheson learned how to set up audio equipment himself for his bands shows. His knowledge of audio equipment brought him work from bands ranging from local acts Jack and the Grease Guns to the world famous Sonic Youth.

“You just learned to do it as you went. I lived way out in the country. There was nobody to learn anything from, so I would read, ask questions in the music store,” said Matheson. “Peavey used to put out a thing called the ‘Peavey Papers.’ It had all the information in there about how to wire a mic, speaker cable, or how you hook up a PA system.”

In the 1980s, Matheson began running sound for Rockafellas’ in the Five Points bar and restaurant district that dominated the local music scene. Running sound for notable acts like Black Flag and Suicidal Tendencies, as well as playing in his own bands, only enhanced his love for heavier music.

“The great thing about working at a place like Rockafellas’ is you would do sound for some big national acts,” said Matheson. “You come in and they have their own sound guy; they give you a chart of how they want the stage, you mic the stage for them, then you watch them do it.”

Opening the studio

Between sound gigs and playing in his own bands, Matheson became interested in recording. He saw an untapped market in the scene and began producing records for his friends’ bands under his new studio, The Jam Room, in the early 1990s.

“I would record them and they say, ‘Maybe the reason I haven’t got a lot of work recorded is because there was no place to record in Columbia.’ There were places, but they were expensive and they couldn’t yield good results,” said Matheson.

While he was not looking to cover the genre, Matheson stayed true to his roots, and The Jam Room became a southeastern hub for recording hardcore music. He had no problem being around the “crust” crowd, full of musicians who did not bathe.

“In that era you were recording on tape machines and consoles, and most people could not operate those things, let alone even hook them up, let alone afford them,” said Matheson. “The people that could afford that kind of stuff, they weren’t looking to record hardcore bands.”

Music culture in Columbia

Columbia’s underground music scene grew throughout the 1980s and 90s. When Hootie and the Blowfish reached worldwide fame, the dynamic of the Columbia music scene — for better or worse — was changed forever.

“All of a sudden, the idea of being a musician, you could wear short, regular old shorts and your favorite football teams t-shirts and be on stage rocking out,” said Matheson. “It was considered perfectly cool, which when I was coming along, that was not the thing at all. Some people still frown on that, but it really did change things.”

Matheson believes this trend created a divide between the musicians and “regular people” of Columbia. As the music became more casual, audiences made attending artistic events around the area less of a priority, in favor for trendier pastimes.

“We go to bars and restaurants that our friends own,; we go to events at the Museum of Art and all kinds of art crawl events… we don’t go to football games for the most part like what normal people do,” said Matheson.

Though expectations regarding the music scene were changing, the popularity of music culture boomed through the turn of the century. It suddenly seemed like anyone could dress or act like a rockstar with ease.

“The musicians back then were outcasts and weirdos. Now you got parents paying money and shoving them into these schools and trying to make them get in bands,” said Matheson.

This trend is much different than the culture Matheson grew up in. His parents did not want him to get into the music business for fear that it was too “sleazy,“ which he will admit it can be.

“We had to hide our instruments we bought from our parents, not even let them know ‘cause they thought we were going to get into trouble and drugs with these guitars and things that we were buying,” said Matheson.

While this cultural shift was occurring, the studio evolved from recording locals to promoting the professionals of the hardcore music genre. Record labels would send bands to record at The Jam Room while they were on tour. Matheson tracked for bands such as In/Humanity, Stretch Armstrong and Initial State.

The Jam Room’s future

Over time, the studio grew to accommodate a more diverse array of music, from solo artists to blues records. Matheson also said that they recently added a grand piano to their arsenal.

“We never thought that the old hardcore studio would be the only studio in town with a grand piano,” said Matheson.

The Jam Room saw a decrease in business when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Matheson believes bands are disheartened by the lack of opportunities to play live music and not recording at the rate they used to.

“A lot of local bands are very driven by just playing New Brookland Tavern or Art Bar,” he said. “If you can’t play there, they really can’t get very fired up to go to practice and write songs and persevere with what they’re doing.”

Despite decades of recording experience and an impressive discography, he is still looking to improve the music that he puts out. His current band, Brandy and the Butcher, continues to record their own music and were in the midst of promoting a new album when the pandemic hit.

“I still want to make some more really awesome records though for another five years or so,” said Matheson. “You start wondering if the studio will continue after you, if you will sell it to somebody or if you’ll just close it down and sell it off piece at a time.”

Matheson continues to be inspired by the music culture he fell in love with as a kid. Amid the current age of music, he is unsure that the hardcore scene that The Jam Room promoted will persevere.

“It’s always cool to meet some of the younger kids that actually remind you a bit more of yourself,” Matheson said. “There’s always those mixed in too, but it seems like numerically, there seems to be less people with a real attitude about being rock stars than there used to be.”

The Jam Room in Columbia began by recording hardcore music, but has since evolved to showcase every genre.

Matheson learned how to operate audio equipment from reading manuals and observing professionals who played gigs at the bars he worked at.

The studio has called it’s Columbia location off of Rosewood Dr. home for over 30 years, and Matheson plans to keep recording more records in the future.