Nonprofit organization Homeless No More’s Family Shelter provides housing to 17 families for up to 30 days. The shelter is one of three housing programs at the organization, which also offers transitional housing at St. Lawrence Place and affordable housing at Live Oak Place. Photos by Nick Sullivan.

First in an occasional series on housing and homelessness

It started as a typical school day for a Richland County high school senior. But when she left school at lunchtime to grab a bite at her house, she found all her belongings strewn on the sidewalk. She’d been evicted, and her mother was nowhere to be found.

With no place to go, the student began sleeping on friends’ couches every night. Even though she had no home of her own, she didn’t qualify for housing services since she was not living on the street.

She briefly moved in with an aunt in Charlotte, but issues with class credit transfers forced her to return to South Carolina. There weren’t many options out there for a student in her situation, according to Abby Cobb, a school-based social worker for Richland 2 school district.

“Her only way out, and the only thing she could think to do, was go into the military because there she would have housing. She would always have a stable place to live,” Cobb said. “There’s lots of stories like her.”

Cobb and other social workers wrestle with such heartbreaking scenarios every day as they work with the “hidden homeless,” people who aren’t living on the streets but do not have a stable address. They surf from couch to couch, double up with other families under a single roof or stay in hotels and motels for extended periods of time.

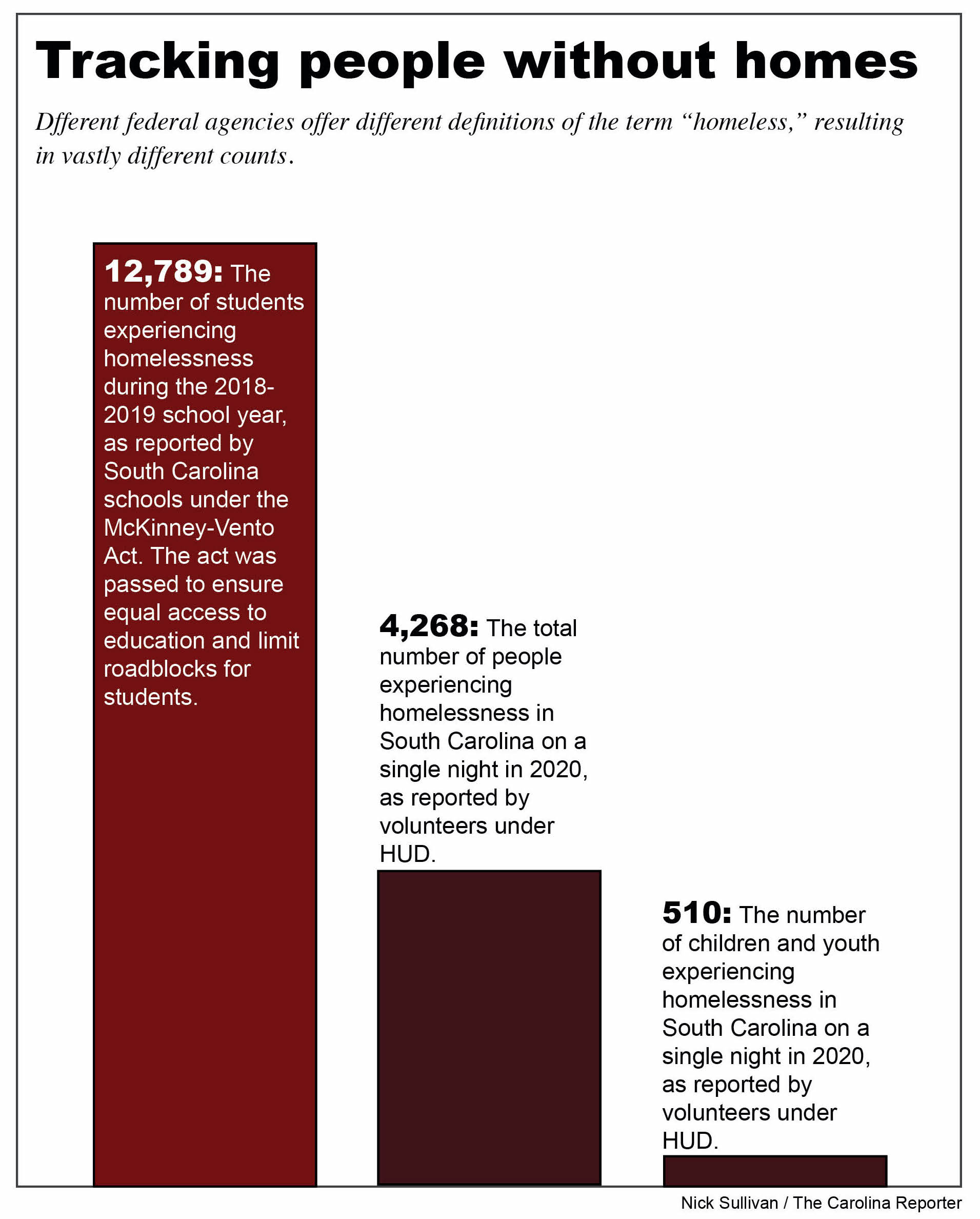

South Carolina schools reported nearly 12,800 students experiencing homelessness in the 2018-2019 school year, the most recent year for which data is available. And depending on who you ask, these students might not be considered homeless at all.

Federal agencies have different definitions of “homeless.” Though they provide structure to organizations serving the homeless population, the discrepancies complicate the process for the hidden homeless, who often fall through the cracks. In some cases, agencies such as the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development restrict services to people exclusively living on the streets.

These definitions exclude the hidden homeless, which Lila Anna Sauls, president of Columbia’s Homeless No More, said is simply “ridiculous.”

Homeless No More is a nonprofit organization that addresses family homelessness through three housing programs, each with its own criteria for who is eligible. The definitions make it more difficult to offer emergency services to the hidden homeless.

“I think that’s where we kinda get bogged down in the weeds. Is that any different than living in a car or on the street? No,” Sauls said.

The U.S. Department of Education accommodates the hidden homeless under a much broader definition, as defined through the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. It was passed to remove barriers to school enrollment for children experiencing homelessness.

The result is a data disconnect, according to Sauls. Families and youth are most affected by this lack of a streamlined definition.

South Carolina counted nearly 4,300 individuals experiencing homelessness in the annual point-in-time count in 2020, in which volunteers counted the homeless population on a single night by surveying them on the street and pulling data from shelters. The count operates under HUD’s most limited definition of homelessness, reporting about 500 children under 18, a stark difference to the thousands reported by the school-based count.

“We would see that point-in-time number, and I would laugh and say, ‘Wow, that’s as many families that I have in [two of our housing programs] today. You’re telling me that there are no other homeless families in 14 counties?'” Sauls said. “And then I’d go to Walmart the next night, and you’d see two cars in the parking lot with the steamed windows, and you’d know it was children sleeping in the back seat.”

Despite its imperfections, the system is in place to ensure everybody is accounted for somewhere, according to Jeffrey Armstrong, the executive director of Family Promise Midlands, a nonprofit that provides resources to families experiencing situational homelessness.

Organizations such as Family Promise serve as a “safety net” for people who fall through the cracks of other programs with stricter criteria. Though not everybody is eligible for all services, the nuance in these definitions gives direction to the organizations working to keep people housed, and they prevent administrative bottlenecking.

Realistically, Sauls said, it would not be possible to count every single person experiencing homelessness even if the point-in-time count broadened its definition.

Experts say school-based counting of homelessness is also a low estimate because parents might not know about the resources available to them, or they might be afraid to report their status.

“They’re fearful that if they lose housing, then they’ll get their children taken away from them, which is certainly not the case,” said Cobb, who is now the Richland 2 School District McKinney-Vento liaison. “Being homeless is not abuse. It is not necessarily neglect. More times than not, it is just strictly parents are doing 100% all that they can to help their children and their families.”

Most students who qualify for McKinney-Vento services do not qualify for housing resources under HUD, according to Cobb. McKinney-Vento focuses on educational consistency — transportation, meals, tutoring — but at the end of the day, students and their families still might not have stable homes to return to because their housing resources are limited.

“You have to have those requirements; you have to have those definitions. It makes it extremely difficult, though, if you have to do that when you’re on the ground serving families every day, face to face,” Armstrong said.

Some programs require a person to spend the night physically on the street before being eligible for resources, as is the case with Homeless No More’s emergency shelter program. That remains frustrating to Sauls, who must turn away families looking to reserve a space at the shelter before an eviction sends them on the streets.

There’s no simple solution to the problem, but Sauls said she would like to see the definitions streamlined moving forward to focus on prevention and emergency services, which are two clear-cut programs with different definitions.

“All of these rules, I think, were created to keep people housed. They weren’t created out of cruelty,” Sauls said. “They’re just kind of hard to enforce.”

Lila Anna Sauls is the president and CEO of Homeless No More, a position she has held since 2007. Homeless No More is located on Two Notch Road in Columbia.

A sign for the playground is posted outside of Family Shelter. “Kids are not only cared for but have a great time and make new friends,” according to the organization.

Richland 2 employee Abby Cobb sits at her desk with flowers and a “Thank You” balloon. The gifts were sent by a former student whom Cobb supported.

Family Promise Midlands Executive Director Jeffrey Armstrong stands in front of a shelf filled with shoes. UofSC women’s basketball coach Dawn Staley partnered with Family Promise as part of her Innersole initiative to deliver brand-new shoes to children.