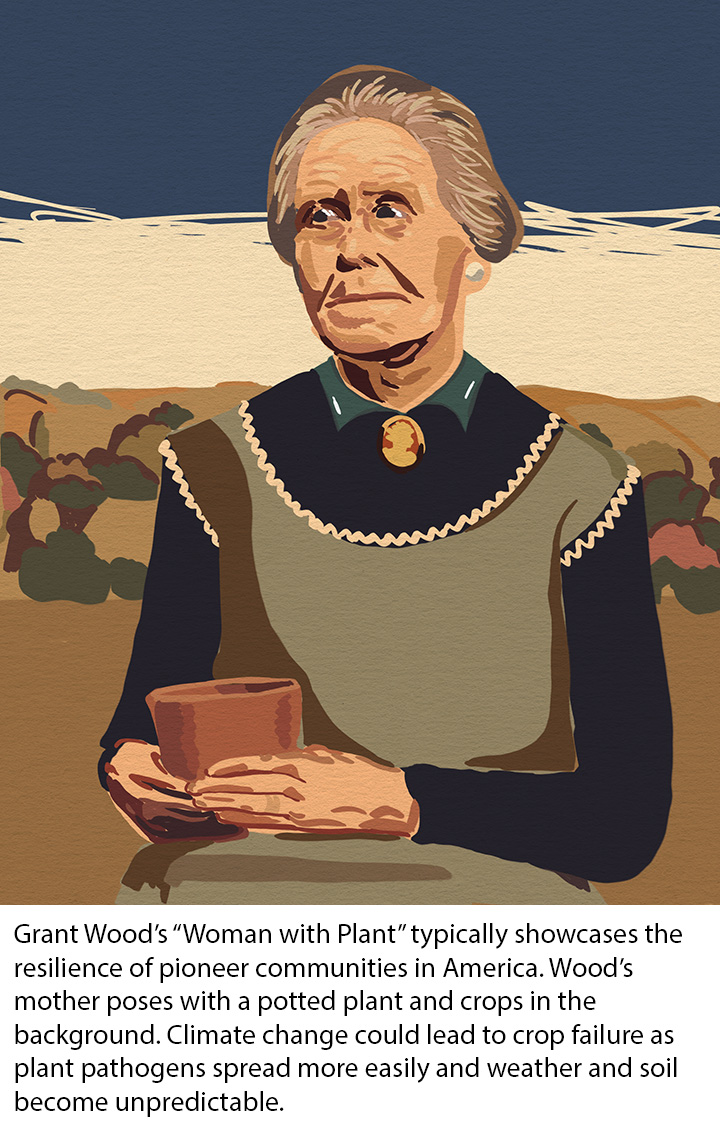

An ode to Norman Rockwell’s “Freedom from Want” to illustrate the potential effects of climate change. Illustrations by Mackenzie Patterson

Climate activists are facing something different from burnout. It isn’t new, but it finally has a name: eco-anxiety.

“For this generation, climate change isn’t something that we just learned in school and just heard about from the news, but it’s something that has arrived at our doorsteps and it’s something that we have faced the consequences of,” said Kiana Kazemi, an activist who lives in Berkley, California. Kazemi has dealt with eco-anxiety for her entire life.

The American Psychological Association defined eco-anxiety as “a chronic fear of environmental doom” in 2017. More recently, in 2020, an APA survey showed that 68% of adults report feeling some eco-anxiety and 48% of young adults feel stress related to climate change in their everyday lives. Many young adults cope with this challenge by immersing themselves in environmental movements and taking to make change.

Kazemi is head of community operations at Intersectional Environmentalist, an online organization dedicated to inclusive environmental advocacy that provides resources and education to activists about intersectional environmental issues. She is also a co-founder of Circularity, an organization that provides education and resources to people dealing with eco-anxiety to help them cope through an online community.

Kazemi is one of the young activists that grew up watching the effects of climate change start to shift the world around her. From flooding to pollution to earthquakes, the potential devastation of the climate crisis grew more apparent.

“On my sixteenth birthday I felt like I couldn’t really get out of bed, I was just really sad for no reason. I felt like I had everything that I possibly wanted and yet the future seemed really sad to me,” Kazemi said. “I think that is the case for a lot of people, especially for people that work in the movement.”

Kazemi, now 21, grew up in New Zealand but was born in Iran and still has family there.

“It was difficult for me to see what my family still in Iran had to face. When we talk about air pollution it’s like nothing that we can imagine here; you know, people are literally dying from it,” said Kazemi. “That was something that I kind of grew up with and having that feeling of eco-anxiety really started to grow more and more.”

Kazemi started sharing her experience coping with eco-anxiety online and found a community that needed help. She said eco-anxiety can appear as a number of different emotions that people wouldn’t always associate with anxiety. For some people it shows up as fear or sadness, for others it could show up as anger.

Different organizations address eco-anxiety in different ways. Some take a wellness based approach to help with the mental stresses of the work. Others promote community-based or individual activism.

“Some people are just waking up to the realities of the climate crisis and what that means for people, so they’re only now starting to feel these emotions, these symptoms, and haven’t had that long period of time to really build those systems for themselves, to regulate those emotions,” Kazemi said.

The APA, Kazemi, and other activists agreed on an important point: communities of color and other marginalized communities

are disproportionately affected by climate change and, in turn, are disproportionately affected by eco-anxiety. Climate activists feel eco-anxiety as a result of the constant onslaught of news about the topic, but some communities feel it because they are watching climate change happen around them.

Jensen Quinn is the director of education and resource management for the environmental organization Post-Landfill Action Network. It focuses on a blend of social justice and environmental work on college campuses to help students facilitate change. Before joining the PLAN team, Quinn, who uses they/them pronouns, was involved in justice programs at the College of Charleston, where they were graduated in 2019. They now live in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where PLAN is based.

Jensen Quinn is the director of education and resource management for the environmental organization Post-Landfill Action Network. It focuses on a blend of social justice and environmental work on college campuses to help students facilitate change. Before joining the PLAN team, Quinn, who uses they/them pronouns, was involved in justice programs at the College of Charleston, where they were graduated in 2019. They now live in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where PLAN is based.

“It is really hard, especially as someone who wants to be really engaged. Thinking about the time limit is something that comes up for me a lot,” Quinn said. “There’s not enough time, we’re running against this clock that is inevitably going to run out. There’s a lot of fear associated with that.”

Quinn, 24, sees the pressure that the urgency of the climate crisis is putting on young people in the movement in light of the recent IPCC report. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released the report earlier this year which concluded that we may have less time to handle climate change than originally thought.

Recent headlines from the COP26 summit in Glasgow led some activists to speak out online about the disappointment of seeing fossil fuel industries heavily represented at the climate conference.

“There’s a desire for me to distance from the onslaught of headlines and climate disaster infographics and the idea that the planet is dying and so are we. I think there’s in that messaging a lot of this collective sense within young people of ‘we are the ones that need to be the saviors of the planet,'” Quinn said.

Quinn, like Kazemi, grew up hearing about the climate crisis. They heard the language surrounding climate issues shift and watched new ideas enter the climate change playbook. Quinn said that activists are “living history now.”

Sammy Fretwell has been covering environmental topics for The State since 1995 and has seen people become more informed over time.

“I think the attitudes have changed, people are a little more knowledgeable about climate change just because it’s been written about increasingly,” Fretwell said.

He explained that the problems and the stories surrounding climate change have existed for a long time, but the troubles people were facing – including more violent weather and coastal erosion – weren’t being attributed to climate change. As South Carolinians became more informed, they began to understand that something was happening, even if they didn’t agree that climate change was a man-made problem.

In South Carolina, the climate change issue to watch is flooding from heavy rain and rising sea levels. Fretwell said that not much public policy is being introduced to prevent these disasters, but policymakers are making plans to react to the aftereffects.

In South Carolina, the climate change issue to watch is flooding from heavy rain and rising sea levels. Fretwell said that not much public policy is being introduced to prevent these disasters, but policymakers are making plans to react to the aftereffects.

“There’s always a chance that something will be done but it just seems like there are so many hurdles to overcome to get some kind of meaningful carbon controls and other types of controls that it just seems like it’s gonna be difficult to do this,” Fretwell said. “We’ll see, maybe I’ll be wrong.”

The pessimism that Fretwell describes is particularly potent for climate activists who often share a bleak worldview about the pace of change, which can cause eco-anxiety. They aren’t fighting another person or a physical threat to the environment that they can easily defeat, they are fighting systems that often choose to react instead of act.

“It’s this dichotomy of being really hopeful but also understanding that getting to where we need to be is really difficult,” Kazemi said.

Despite this, Kazemi and Quinn cite getting involved with the community as a way to combat eco-anxiety while making productive change to prevent it in the future.

“A lot of times we feel like we are alone in this and that we should deal with all of these emotions, all of these really traumatic experiences, on our own,” Kazemi said. “But, when we find that almost everyone else around us is feeling the same way and that we can lean on each other, we can support each other, we can share our experiences with one another, that just makes things so much better.”