A number of congregations across South Carolina lost their pastors to the coronavirus. Free Will Baptist Church in Chester is still recovering from the death of the Rev. James “Jimmy” Sanders, but has welcomed a new minister to the pulpit.

CHESTER, S.C. – Coronavirus took the pastor Michelle Cassady had known most of her life. The Rev. James Sanders led the First Free Will Baptist Church for 28 years until he died from the virus in November 2020.

Cassady is at the church campus almost every day as the administrator of Hawthorne Christian Academy, the school that Sanders opened in 2002. On its website, the K-12 college preparatory school describes itself as a place that “teaches Biblical principles to prepare young people with a Christian worldview.” She has attended First Free Will since she was a child and, like most of the adult congregation, sees the church as central to her life.

“He went to our sporting events when we were in high school, he performed most of our marriage ceremonies, he was at our graduations, he was there when our children were born. My first daughter, he was late for church waiting on her to be born,” Cassady said.

First Free Will Baptist wasn’t the only church to lose their pastor to COVID-19 – a pastor in Moncks Corner lost his life to the virus in September and Resurrection Life Ministries in Columbia lost its pastor to COVID in February. Those congregations are not the only ones that dealt with the emotional toll of the pandemic.

Congregations across South Carolina, in the heart of the Bible Belt, have suffered the effects of the pandemic as services have gone virtual and church pews sit empty.

“I’ve had several members that have been able to come inside express to me, it’s not the same. Not being able to really interact,” said the Rev. Rodney Adams, pastor of Big Calvary Baptist in Edgemoor, South Carolina.

Nationwide, church attendance suffered during the pandemic. Last year, the percentage of Americans who attended religious services, either in-person or remotely, dropped to 30%, its lowest point in more than eight decades, according to a Gallup poll.

While attendance has ticked up slightly, it still falls below numbers from before the pandemic.

Monumental Missionary Baptist Church in Florence saw its numbers dip from around 100 gathered on a Sunday to around 65, but its leaders find hope in what they see as new opportunities.

“The ministry of the church has spread beyond their walls,” said Terry Alexander, an associate pastor at Monumental, “And yes, we need to come together and fellowship, but we’re finding out now that it’s not the building that makes the church, it is the believers that makes up the church.”

Other pastors, like Adams, found the pandemic forced them to be more creative with their approaches to ministry by embracing online opportunities.

“They (the congregation) hear from me a lot more frequently than they ever did,” Adams said. On Monday and Friday mornings, he hosts a virtual morning meditation. He believes his congregation will continue with online opportunities.

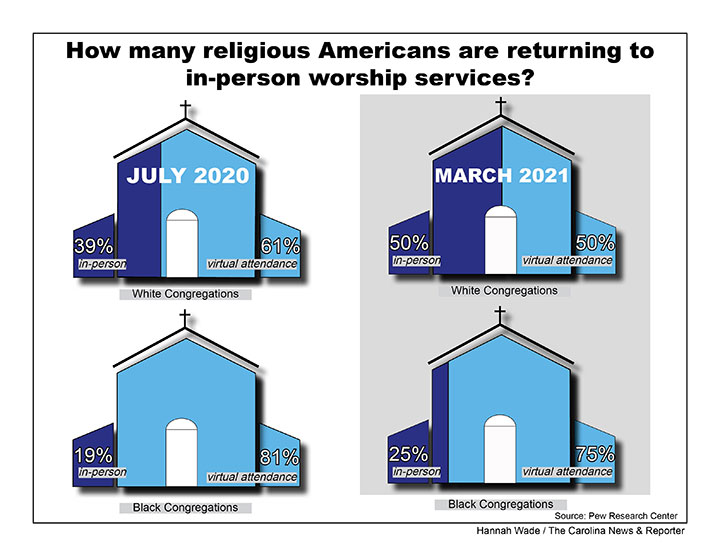

Southern churches dealt with COVID-19 in different ways. Predominantly black churches tended to proceed with precaution, while white evangelicals embraced worship in-person. Mainline denominations, including Lutherans, Presbyterians and Episcopalians, tended to be more cautious.

As of early March 2021, nearly 50% of white adults said they attended a church service in person in the last month, while only 25% of black adults said they had returned in person, according to the Pew Research Center.

For pastors of predominantly black churches, like Adams, the need to keep their congregations safe outweighed the desire to meet in person.

“You have to hope for the best, but plan for the worst so you make decisions based on the person that would have the greatest level of concern for their safety and you operate from that perspective so that you are inclusive of everyone,” Adams said.

His church brought in around 120 to 140 people on a typical pre-pandemic Sunday. While chairs started filling back up when the vaccine became available, the church is still missing about 30% of its population.

Black mega-churches, like Brookland Baptist Church in Columbia, held vaccine clinics and played a role in encouraging members to get vaccinated. Church leaders pushed education to alleviate distrust in vaccines and medicine that lingers for many African Americans, who know all too well the history of medical abuse in the United States.

“The pastor’s concern is about one’s well being, not just their soul, but also their physical being and how they are here on earth and so we, as any other church, had to make some concessions you know and you have to trust the process that eventually this thing will be over with,” Alexander, of Monumental Missionary, said.

First Free Will, a predominantly white church, who lost Sanders to the virus, followed protocols. When the pandemic struck, the church moved online. They started meeting back again late summer of 2020, with masks on and pews sectioned off for social distancing.

South Carolina lawmakers and Gov. Henry McMaster made it easier for churches that wanted to stay open to do so, refusing to shut down churches by classifying them as essential businesses. Some in South Carolina never stopped meeting for worship.

“The thing about it is, we really never stopped having services,” Rev. Tim Foster, the pastor of Cornwell Presbyterian Church in Chester, South Carolina, said.

Cornwell Presbyterian moved to “drive-in” services for a while – where congregants could drive up to the church and listen to the sermon through their radio. About a half a year into the pandemic, the congregation said “what the heck” and moved back inside, Foster said.

In March 2021, state lawmakers passed a bill ensuring that churches would remain open in other emergency situations and under different leadership. One of those lawmakers, Rep. Mike Burns from Greenville, has been attending Enoree Baptist Church in Travelers Rest his whole life.

“The governor was shutting down a lot of things. Churches, he made clear he wasn’t going to but he won’t always be the governor,” Burns said. “We wanted to ensure that South Carolinians who want to worship can go to church.”

His church stopped meeting briefly last year and then, like many rural churches, transitioned to “drive-in” services. Now, they’re back in person and inside the building.

“It’s pretty much business as usual right now. I mean I didn’t see a soul with a mask on yesterday,” Burns said.

While attendance numbers continue to creep up, concerns still exist about whether or not some church-goers will ever return to in-person services.

Pastors expressed worry about members who had “slipped through the cracks” and are hesitant, for health-related or other reasons, to return.

Foster, from Cornwell Presbyterian, struggled to find a line between encouraging folks to come back to church and recognizing the fear his members faced about catching COVID-19.

For First Free Will, its services remain forever changed. Sitting six feet apart as a new pastor speaks from the pulpit has been hard for even the most faithful of members.

But Cassady said the grief from loss has turned to praise over the last year as they embraced the new pastor, Kevin Johnson. The congregation is building on the legacy that Sanders left behind – through his wife and children and through the church.

“I think that, as a church, the people realized after he passed the importance of trying to truly honor the legacy he was trying to leave,” Cassady said.

Michelle Cassady has attended First Free Will Baptist Church since she was a child. The late Rev. James Sanders was like a father figure to her, attending her high school sporting events and graduations, officiating her wedding and attending the births of her children.

South Carolina State Rep. Mike Burns, R-Greenville, was one of the lawmakers who introduced the bill to keep S.C. churches open in future emergencies. The bill passed in May 2021.