The COVID-19 pandemic began in March 2020, but nurses are still feeling the stress as staffing shortages pursue and protocols continue to change, two years later. Photos courtesy of Prisma Health.

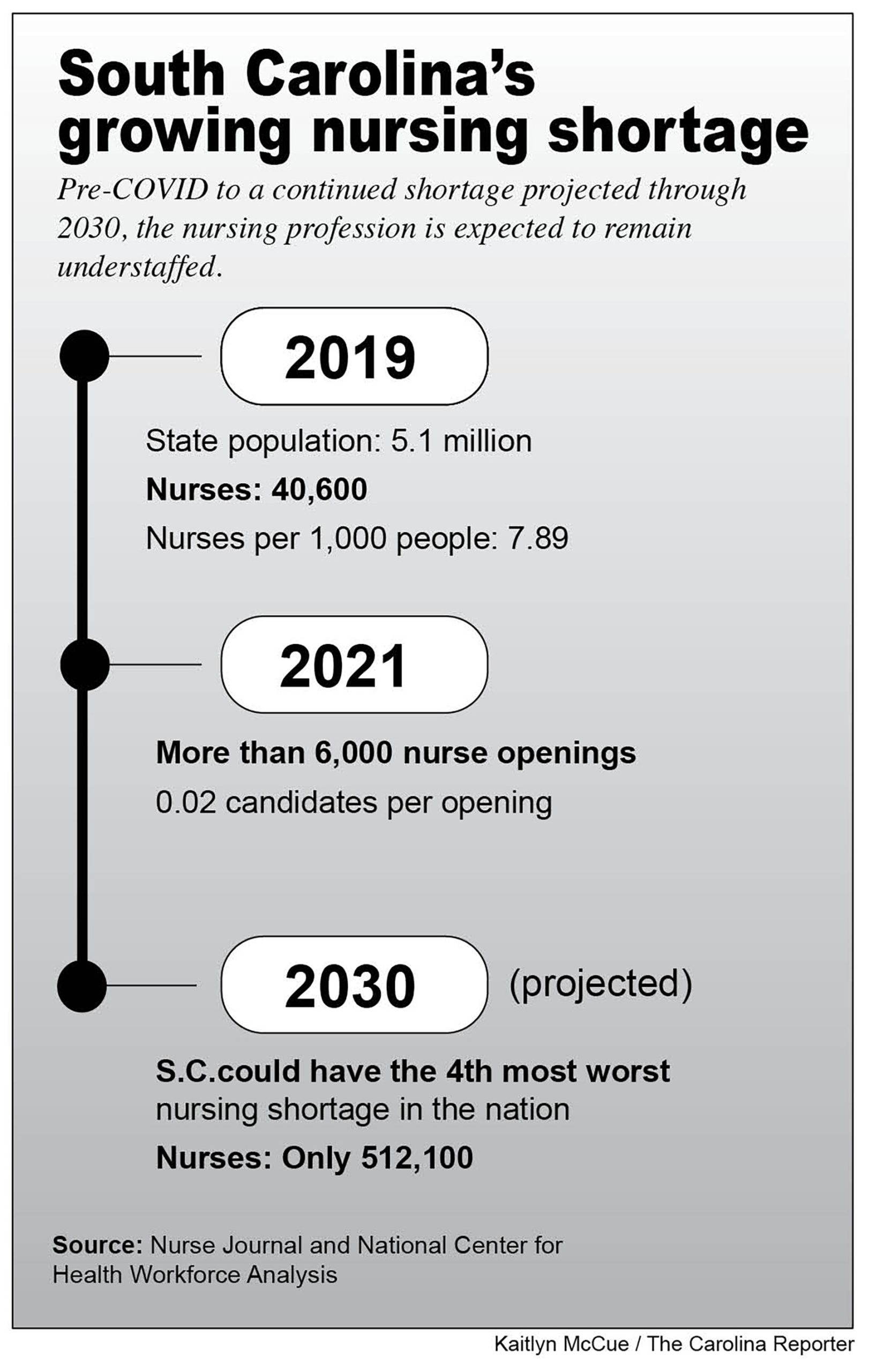

Before the pandemic, South Carolina had one of the most severe hospital staffing shortages in the country, with just under eight nurses per 1,000 population in 2019, according to NurseJournal. Two years into the pandemic, the staffing shortage has only worsened.

A data study by the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis shows South Carolina is expected to rank in the top five states with the most severe staffing shortages by 2030. The state is truly struggling to keep up with demand.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended that nurses and hospital employees cut their quarantine times to make up for staffing holes in hospitals across the nation. According to the CDC protocol released in December, if symptom severity is lessening, nurses can go back to work even if they’re COVID-positive.

Samantha Dupree, a nurse at Prisma Health Richland, works in the heart hospital, where nurses are being sent to other departments because staffing shortages are so severe. Because of this and the new CDC protocol, nurses are coming back to work earlier than Dupree thinks is safe.

“They’re not really making people work with COVID, it’s just that those five days are not enough. I think people are still contagious, it’s just not enough time to recuperate,” Dupree said. “In the middle of a shift change I had to send a nurse to another unit because another nurse fainted after coming back too early from having COVID, and that was the second time, the second nurse.”

Prisma has utilized an incentive program in an attempt to combat the staffing problem. Although the hospital is not offering COVID pay, it is offering bonuses for nurses who volunteer to take on an extra shift per six-week period. The hospital has also enacted protocol for all staff to wear N-95 masks, whether they work with COVID-infected patients or not.

Despite this health precaution, some patients at the hospital have tested positive after being hospitalized for something else, Dupree said. She said she feels much safer knowing everyone is wearing N-95’s and remaining cautious.

Much of the staff, “especially the newer nurses, are going to do what [the CDC] says, and come back early because they don’t want to disappoint, even if they aren’t well enough,” said Dupree.

The nursing shortage remains a crisis across the state. Even the fast growing hospital, Medical University of South Carolina, is feeling the pressure of empty hospital halls.

“A lot of things have changed. We are severely effected by the Great Resignation,” said Leah Ramos, executive director of nursing for the adult unit at MUSC Charleston.

MUSC has implemented multiple programs to assist with this crisis, from creating “Zen rooms” for staff and resiliency classes to offering bonuses for extra shifts, much like Prisma Health’s program. MUSC caps a nurse’s work week at 60 hours, with overtime, rather than a typical 36-40 hours. The hospital also emphasizes mental health assistance for all staff.

“The increased workload because of the shortage, it has really increased burnout, and the burnout will effect how [nurses] are caring for their patients,” said Ramos.

Recruitment, retention, and resilience are the main focuses for leaders at MUSC, not only for bedside nurses, but also for each other as hospital leaders. However, despite efforts to maintain staff and recruit as well as retain nurses, the shortage has managed to hit the hospital hard.

“Before the pandemic, our turnover rate was at 16%, now we are at 26%,” Ramos said.

Other new programming such as the South Carolina Nurse Retention Program, which awards up to $24,000 to graduates of University of South Carolina-Beaufort or the Technical College of the Lowcountry, are aiming to combat the nursing shortage. However, prospective nurses are still questioning their career paths due to the effects the pandemic has had on hospital nurses.

“It’s honestly scary being a baby nursing student and seeing all the stuff happening at the moment with nurses and COVID,” said Alyssa Charbono, a Midlands Tech nursing major from New York.

Charbono has dreamed of being in the medical field for as long as she can remember, and the pandemic strengthened her drive to help people.

“Not only do they want nurses to put their lives in danger but they also don’t want to compensate them correctly. But then they complain about not having enough people to work in the hospitals,” said Charbono, “it’s just a chaotic time to be a part of the health field.”

These issues also have potential to affect the patients already struggling to find hope in their situations. According to Dupree, partially due to the pandemic, hospital staffs become a patient’s family because so many of them do not have family members visiting them. When this familial aspect disappears because a nurse quarantines or is at work sick, the whole hospital faces consequences.

“When you come back too early, we end up short staffed and then patients end up not being taken care of,” said Dupree.

Because of issues like this, Ramos urges everyone who may find themselves interacting with hospital staff to “please, just be kind.”