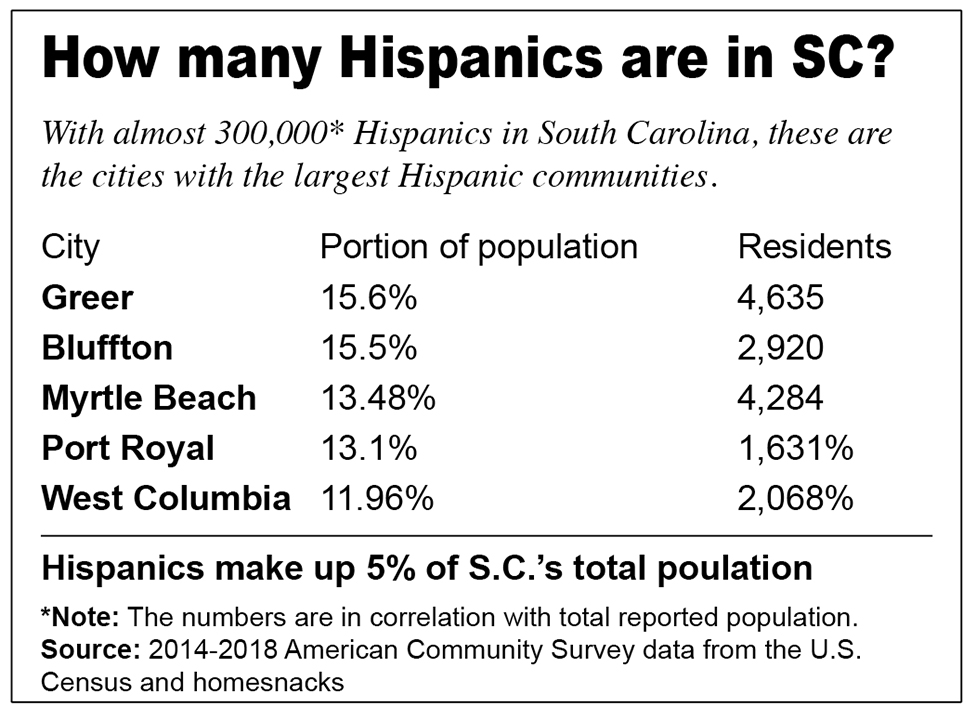

The Hispanic community continues to grow in South Carolina, although some experts and community activists believe the growth is not reflected in U.S. Census.

In 2010, the Census reported that there were 235,682 Hispanics living in South Carolina.

“It really was more like 400,000. You can see that the numbers are a lot higher than what the census is gonna say,” Ivan Segura, Hispanic/Latino affairs program manager at the S.C. Commission for Minority Affair, said. “The fact that [the population] is growing so fast still makes it an emerging community.”

As an emerging community, the Hispanic population is still adjusting to being in a new home as the numbers consistently rise. However, as it continues to grow, it’s always strongly encouraged to fill out the Census.

But fears about checking a citizenship question on the form has deterred some of the population from even acknowledging it. On top of that, immigrants can even be charged for the public services they use.

“The citizenship question and the public charge became these hot topics for brief moments,” said Mike Young, co-interim executive director and director of capacity for PASOs, said.

PASOs, a community health organization, partners with local agencies and commissions to help connect Latino families with the appropriate resources. They aid in health benefits, child development and more.

“It was intentional and it did the damage that it needed to do and that really stinks because a lot of the programs that these people qualify for don’t affect their public charge or their qualification to become a citizen,” Young said.

In March 2018, Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross, on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice, announced the addition of the citizenship question on the 2020 Census, claiming it was necessary for enforcing the Voting Rights Act.

It was the first time since 1950 that Census respondents would have to declare their citizenship.

The U.S. Supreme Court came to the conclusion that although it is legal to add the question, the Department of Justice essentially lied about why the addition needed to be made, claiming the DOJ was looking for the data anywhere they could.

“We walk people through it, we don’t just encourage it. We go ‘ten questions, ten minutes, the citizenship question is not on there, don’t worry about that part. It’s gonna help you,’” Young said.

Still, it left many of the Hispanic/Latino population wary of filling out the Census and signing up for certain programs that could potentially reveal confidential information.

“So you see people not signing up for services that would benefit them … and that’s our role, to instill that confidence in them that says ‘Believe me, we know the law, we have lawyers, we can make sure that you feel comfortable’ and that’s what we’re here for,” Young said.

Janelys Villalta, from Beaufort, S.C., and former president of the Latin American Student Organization at the University of South Carolina, didn’t grow up very aware of the Census but understands the importance of partaking in it. She is now working as a news producer for WRDW in Augusta, Georgia.

“The Census is something everyone can take part in, it will help your communities fund the things that are important to you if they found out there’s a huge Latin population; like in Beaufort, South Carolina they’re going to want to fund these things,” Villalta said.

“It brings about $8,000 per person to your local community. For schools, roads, parks and rec and hospitals. We tell people that it matters,” Young said.

Alongside the Census, the upcoming presidential election has risen the ever-present questions about voting.

“I think that’s something that a lot of Latinos struggle with. It’s figuring out not only if they can vote it’s how they can vote and stuff like that. I think over the years its gotten better because a lot of these organizations like scvotes.org has Spanish options now,” Villalta said.

According to the Pew Research Center, Latinos make up 13.3% of all eligible voters, which is only half of the 60 million Latinos projected to be living in the U.S.

Therefore, it’s crucial that those who have the ability to vote know exactly what they need to do.

“Not only do you have to translate these documents into a language other than English, you also need to understand what’s the best way to get information to the people that need to know this information,” Segura said.

Now, with most documents and websites having English translations, information has become increasingly easier to gather and eventually understand.

“But growing up, it was like ‘What? People who speak predominantly Spanish can vote in this country?’ It wasn’t a thing so there’s been a lot of progression with that,” Villalta said.

For more information on how to vote you can visit https://www.scvotes.gov/como-votar