Almost 1,000 children from Nairobi came to watch Dance Centre Kenya’s performance of The Nutcracker. (Photo courtesy of Robert Butt)

Inside the largest slum in Africa sits a dance center that has its origins in Columbia, South Carolina. Dance Centre Kenya in Nairobi, the country’s capital, has more than 700 students and teaches classes to almost 1,000 additional children throughout the city.

Columbia native Cooper Rust, who now lives in Kenya, founded the nonprofit dance center, Artists for Africa, after traveling to Kenya in 2012 to teach English. She saw a lack of arts opportunities for children and decided to start Artists for Africa — and later Dance Centre Kenya. Rust’s mother, Mims, is also involved but lives in Columbia.

Halfway around the world, in Honduras, a different program with similar goals also got its start in South Carolina. Knowledge Perk, a coffee company that will open a location soon on Gervais Street across from the University of South Carolina School of Law, is using coffee to affect change in that country.

Both programs are rooted in the creativity of South Carolinians, and both have a common goal — to improve the lives of children and communities in poorer countries. The average person in Kenya makes about $1,760 per year, while the average person in Honduras makes about $2,200, according to the World Population Review. Both countries are among the 50 poorest in the world.

NAIROBI, KENYA

Kibera, Nairobi, is the largest slum on the entire African continent, according to a Nairobi Cross-sectional Slums Survey from 2012. The average house is 12 feet by 12 feet, made of mud and concrete and has little to no sewage facilities. Almost 250,000 people live in the Kibera slum in Nairobi. For comparison, Columbia’s population is 134,000.

Artists for Africa exposes schoolchildren in Kibera and surrounding Nairobi to arts such as dancing, singing, painting and acting.

“Some kids were traveling an hour and a half to get to ballet and to get back,” said Mims Rust, Cooper’s mother. “And oftentimes, the families couldn’t afford the 15-cent bus fare to and from, so the kids would walk.”

Since its formation in 2012, Cooper Rust’s organization has worked with the USC dance program to send groups of Kenyan kids to Columbia to take part in its three-week Summer Dance Conservatory.

“For these Kenyans to come in — they’re lovely and charming and wonderful,” said Susan Anderson, the founding director of the Summer Dance Conservatory. “And the one gift they bring with them is humility. They teach our American children how spoiled they are. They’re so grateful for anything and everything.”

The Kenyan children who are selected to travel stateside stay in Columbia for about six weeks. They live in dorms during the three-week program and later stay at Rust’s house to practice for their own separate performance event a few weeks later.

“It’s an unusual circumstance for a 60-year-old woman to have 17-year-old friends,” Mims Rust said. “But how lucky am I?”

Lucky, but often stunned.

“One of the kids came up to me and said, ‘Ms. Mims, can I have some more ice cream?’” Rust said. “I said, ‘Of course you can … it’s in the freezer, go help yourself.’ He walked out of the room, and (my daughter) Cooper said, ‘He has no idea what you just said to him, mom. He doesn’t know what a freezer is.’”

Rust also has had to adjust to Kenya’s customs. She said when she’s in Kenya, she’s treated as a minority — a wealth minority. Police in particular assume she has lots of money because she’s white. She said police often extort people in Kenya because law enforcement are often as poor as the general population. Graft and corruption are rampant.

Mims Rust said she travels to Kenya twice a year to visit her daughter and the children in the program. She’s been able to see the effects of her daughter’s work on the hundreds of schoolchildren in arts classes, and particularly on the handful of kids in the program’s boarding house. The children in the boarding house show promise for a professional dance career.

“(One of the school principals said,) ‘It’s really amazing what it does for their self-esteem,’” Mims Rust said. “He said, ‘I was talking to one of the little girls and I asked, ‘Are you enjoying your art class?’ And she said, ‘I am a ballerina.’ And he said (that) she said it with such pride that it was very moving to him.”

Those involved with Artists for Africa have noted that this self-esteem boost is a common theme among the Kenyan kids.

“There are other organizations that do food and water and provide those necessities,” said Robert Butt, a former board member of Artists for Africa. “What we’re giving these children are something that creates hope for them, gives them an experience they’ve never had, and then gives them something to feel good about themselves.”

Artists for Africa has raised around $350,000 since its formation, Butt said. He said the nonprofit loosely keeps track of the kids who go to college or professional dance companies, but it’s too difficult to keep track of the hundreds of schoolchildren they serve in the slums.

Some of the children in the boarding house have gotten scholarships to colleges in the United States, dance schools in London, and even jobs at the Joffrey Ballet, the prominent dance company in Chicago and New York. Rust said one child recently left Nairobi with a full scholarship to the English National Ballet in London.

Artists for Africa’s work has even reached celebrities. After an article was written about the group for the BBC, Mims Rust said the group got a call from a financial advisor.

“She said, ‘I have a client who saw that (article) and wants to donate some money. How do we do that?’” she said. “We gave her that information. As it turns out, the client was a member of Kiss — Paul Stanley. He sent $10,000.”

Celebrities notwithstanding, Mims Rust said, “Cooper’s biggest contribution to the world is going to be the children who want to grow up and be Cooper,” she said. “So Cooper’s going to leave behind a group of people who do what she does, multiplied by however many of them there are. And I mean, who can say that?”

HONDURAS

Over in Honduras, Knowledge Perk Coffee Co. is using coffee and education as a way to create change.

Honduras is the second-poorest country in Central America, according to The World Factbook. Political instability and gang violence are major contributors to Honduras’ poverty and social problems, according to research from The Borgen Project. Between 2010 and 2018, there were more than 1,500 students killed in gang violence. In the three years between 2014 and 2017, 200,000 children left school altogether — this in a country with only 9 million total people.

“There are not a lot of options for the youth once they get past fifth grade,” said Ryan Sanderson, CEO and co-founder of Knowledge Perk. “By helping support with this particular coffee product, (we can) help finance one of those schools so that the education can continue.”

Knowledge Perk’s first location opened in Rock Hill in 2019 and its second, in Fort Mill in April. Sanderson plans to open a new location in the historic W.B. Smith Whaley House on Columbia’s Gervais Street. The opening date hasn’t been announced yet.

The coffee company began a partnership in 2022 with Educate2Envision, which connects it with coffee farmers in Honduras. Knowledge Perk sells a cold brew coffee from Honduras, and a percentage of those profits goes back to Honduran schools. Coffee is the country’s second-highest export as of 2020, according to The Observatory of Economic Complexity.

“We do hope that (the children in Honduras) can continue to work in the coffee industry, but now they’re able to work in the coffee industry (with) more opportunities and more education, with better resources,” Sanderson said.

Sanderson said Knowledge Perk also works with Unblended, a coffee company from Colombia, in South America. Sanderson said it has helped him form direct relationships with coffee farmers in Colombia rather than working through corporate middlemen.

“(Places like Unblended) are trying to be a lot more intentional about the relationships,” Sanderson said. “And (they’re) taking companies like ours that are very conscientious of not just where our money is going, but who we’re supporting and how we can help those people.”

Jaime Lopez is a farmer in his late 70s from Colombia, South America, whose handpicked coffee has been sold at Knowledge Perk.

“Nobody in the U.S. ever knew who Jaime Lopez was,” Sanderson said. “And we had coffee on our shelf that was the Jaime Lopez coffee. That kind of relationship-building — the guy saw that coffee, (and) he literally started crying. He’d never seen his name on something in the U.S. before.”

Sanderson said Knowledge Perk has recently come out of “survival mode” from COVID, so it isn’t able to keep track of its fundraising numbers or global impacts.

Nevertheless, the work continues.

“I think some small businesses are so focused on growing their company that they lose sight of the people that are on the outside,” Sanderson said. “So, I would just encourage other people to try to focus on both. It’s not easy, but it’s worth it in the end.”

A group of Kenyan children make their way to a park in Nairobi to watch Dance Centre Kenya’s performance of The Nutcracker. (Photo courtesy of Robert Butt)

Dance Centre Kenya puts on a performance of The Nutcracker in Nairobi in 2021. (Photo courtesy of Robert Butt)

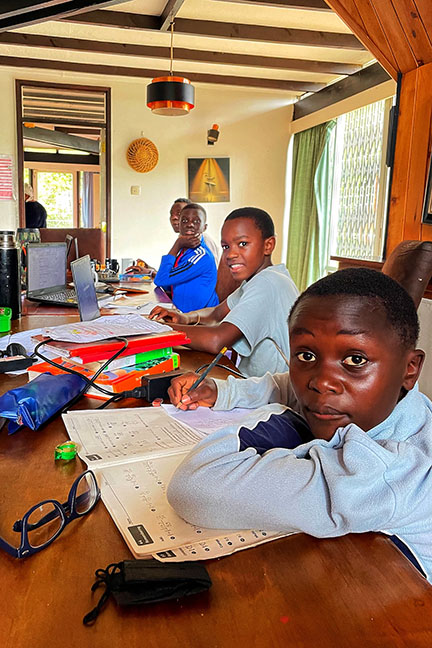

The Kenyan children in Artists for Africa’s boarding house get ready for Thanksgiving in 2021 while doing homework. (Photo courtesy of Robert Butt)

Knowledge Perk’s location in Fort Mill is its second location in South Carolina. Its first location opened first in Rock Hill. (Photo by Danielle Wallace)

The Fort Mill Knowledge Perk has multiple murals throughout its store. This mural emphasizes community and a “better world.” (Photo by Danielle Wallace)

The W.B. Smith Whaley House on Gervais Street is slated to be the new Columbia site for a Knowledge Perk coffee shop. (Photo by Danielle Wallace)