Columbia’s small businesses face many problems, from bureaucratic delays to large property taxes. Columbia’s four mayoral candidates say they have the solutions. The city’s election is Nov. 2. Photos by Jack Bingham

Talk to business leaders around the city of Columbia, and one thing is clear: The city is not welcoming to entrepreneurs.

From the galleries of the Vista to Five Points boutiques and bars to neighborhood convenience stores, business owners and representatives citywide decried fees, taxes and other obstacles to their work in the city.

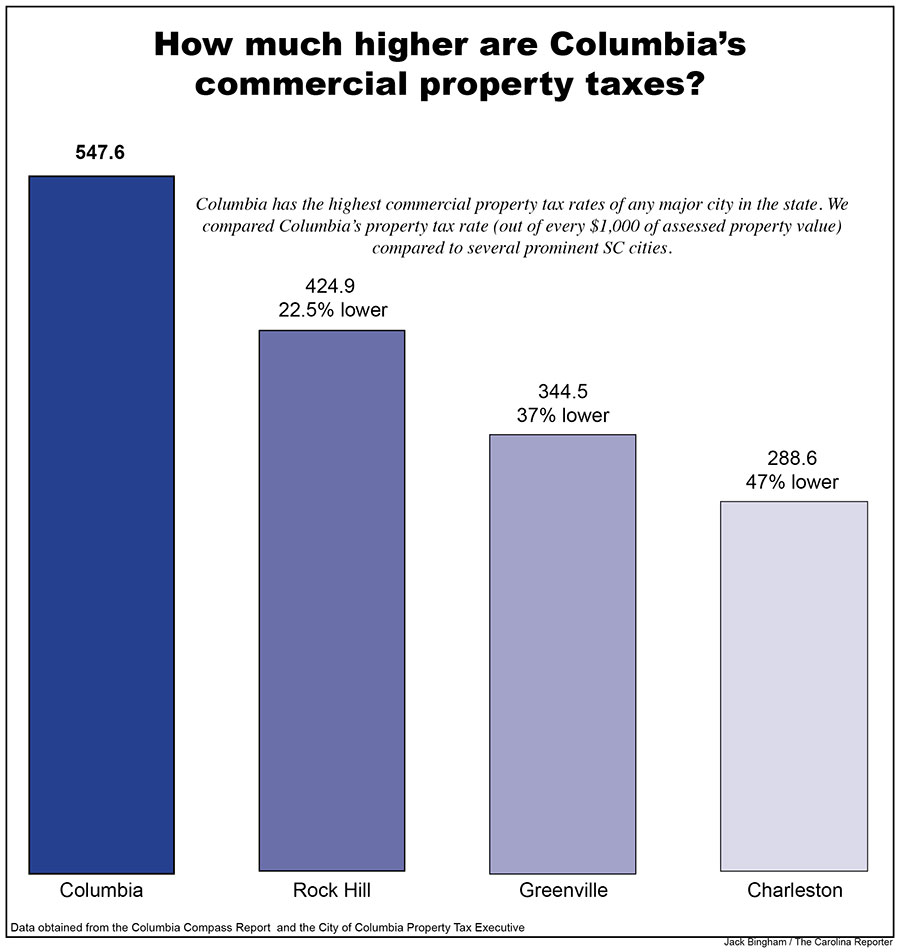

Columbia’s commercial property taxes are so much higher than elsewhere in the state – 47% higher than Charleston’s, for instance– that many business leaders believe they’re a roadblock to their work.

“If my restaurant got wiped out in a hurricane and I had to reopen it, I don’t know that I’d do it in Columbia. I don’t know that it’d be possible,” said Steve Cook, president of the Five Points Association and owner of Saluda’s restaurant. He is among the most outspoken critics of a city government that he says is mired in inefficiency and ineffective at clearing a path for fledgling small business owners.

“There’s so many groups in Columbia that have so many disparate outcomes that they just end up splitting the baby,” Cook said.

Cook isn’t alone. Business leaders around Columbia echoed his sentiments on the difficulty of starting and maintaining a business in the city.

Matthew Marcom, a franchise owner of Pelican’s SnoBalls and leader of the Greater Rosewood Merchants’ Association, expressed concerns about the city’s bureaucracy.

“City ordinances and red tape keep out some hyper-small businesses, people who are taking the step from ‘Oh, this is something I enjoy,’ to a way they try to make a living,” Marcom said.

Tia Brannon, owner of Carolina Hair Studios on Main Street, said she was met with bureaucratic barriers while trying to obtain city funding in 2013 to establish her business.

“They said ‘Oh, we’re gonna give you a loan. Just bear with us,’ and then finally, they call me and say, ‘Oh, we’re doing a restructure,’ three months later. So at that time, I didn’t have time to investigate what was the deal; I had already started my business,” Brannon said.

Despite her high credit score and $40,000 in liquid assets, Brannon never received the loan, and was never told why.

Brannon’s not the only one to experience frustration with the slow pace and convoluted path involved in opening a small business. Cook said city officials may take weeks or months to inspect property, list necessary changes or approve business licenses.

“People feel beaten down by the time their businesses open,” Cook said, “I’ve certainly felt it.”

This beat-down feeling continues, said Sunrise Bath and Body Works owner Tzima Brown, because of Columbia’s taxes. Although she received a grant from the city to improve her business’ facade, she said something “should be done” about local property taxes.

“The city of Columbia has done so much for me,” Brown said, “but [small business owners] pay more taxes than anybody. We don’t have accountants that are able to wiggle us out of having to pay taxes at all.”

Small business, high taxes

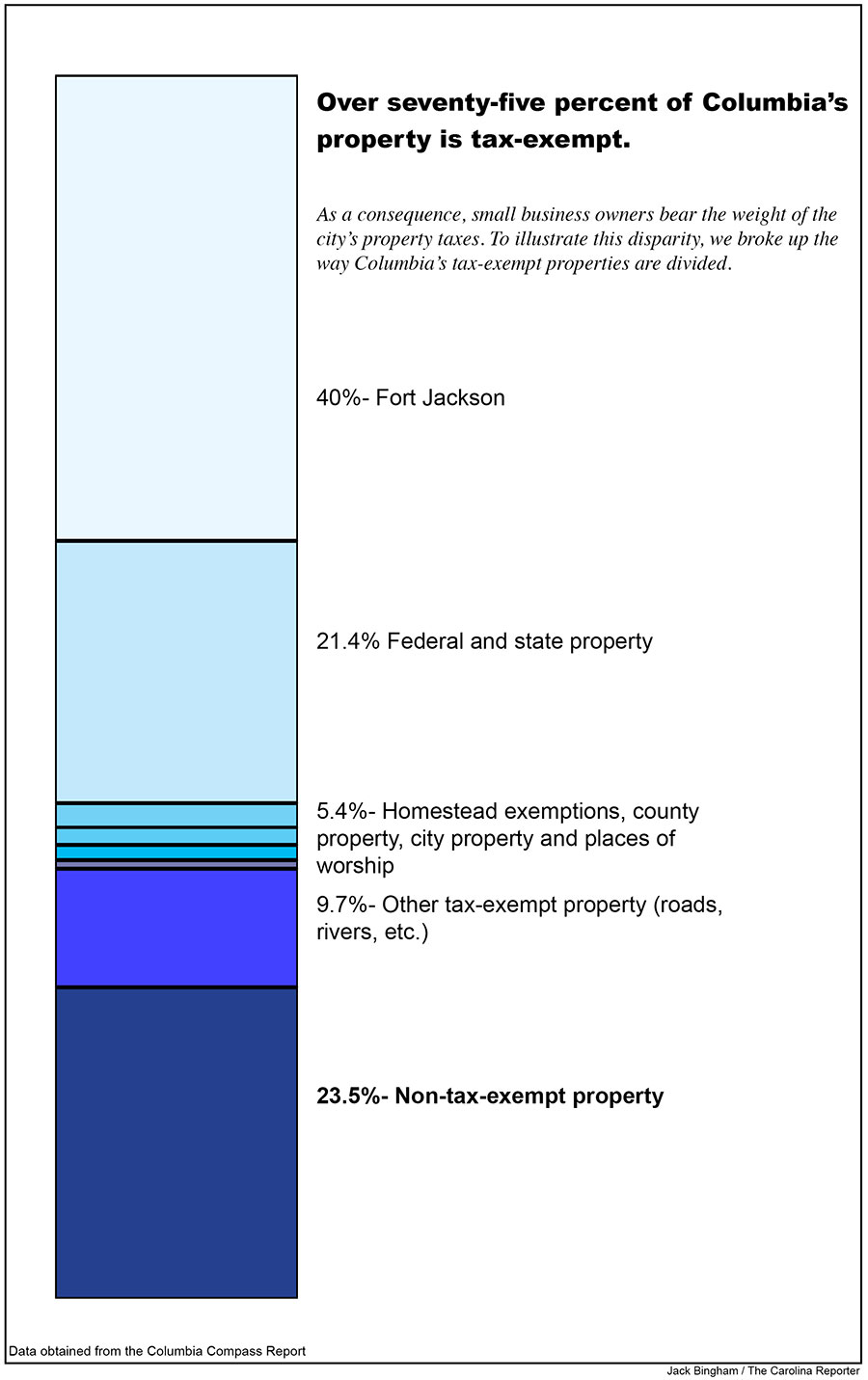

Columbia’s commercial property taxes are so high, said mayoral candidate and law firm owner Tameika Isaac Devine, because of the city’s large amount of tax-exempt property.

This includes state-owned property, universities and churches.

“The brunt of taxes in Columbia are shifted onto small business owners,” Devine said.

The city’s Columbia Compass report states that 76.5% of Columbia’s property, including Fort Jackson’s sprawling U.S. military installation, is tax-exempt.

The city’s property, Devine said, is also “depressed” in value compared to comparable cities. As a consequence, higher commercial taxes are necessary to rake in the same amounts of revenue as cities with more valuable property.

Additionally, the cost of starting a business is astronomical, Cook said. Depending on the size, location and type of business one is looking to start, he said, it can be a multi-step process that can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

“You wanna start a business? You gotta be a developer, you gotta be a rich guy, you gotta be a corporation,” Cook said. “The little guy doesn’t stand a chance.”

All the above facts, Cook said, lead to prospective business owners looking elsewhere to set down roots.

“You go to West Columbia or Cayce, they’ll say ‘Oh, what can we do to help?’ They’ve got a small group of employees that can make decisions in the moment,” Cook said. “Here, everybody with a desk has to justify their desk.”

Candidates offer array of fixes

The Compass Report makes suggestions for how to alleviate these issues, the main one being: Explore fees for tax-exempt institutions. Such fees could include compensation for city services, such as drainage and streetlights, or payments in lieu of taxes, which are voluntary.

While City Planning, the government agency that developed the Compass Report, was not available to comment, Devine said that such fees are “tools in our toolbox,” but that there are “no big things planned at this second,” regarding efforts to change the city’s commercial tax structure.

Devine, along with Columbia’s other mayoral candidates – Councilman Daniel Rickenmann, former mayoral aide Sam Johnson and former Councilman Moe Baddourah – have suggestions of their own.

Johnson, after eight years as the mayor’s aide, would turn to the city’s government to solve the problem. He would appoint an ombudsman for each city council district in order to direct business owners and other citizens to the city office appropriate for their needs.

“As opposed to you getting in touch with a city council member who’s got a day job, a family, and maybe won’t pick up the phone… let’s make sure we have the necessary personnel to really handle Columbia’s situations and challenges,” Johnson said.

Johnson calls this solution an “immediate fix” to bureaucratic inefficiency in Columbia.

Rickenmann, an owner of businesses that include renewable energy generation and food production, has targeted Columbia’s high tax rate as the source of its “unfriendly business reputation.” Rickenmann pushed for a city-wide study into Columbia’s taxes last year, available here.

“We’ve got a challenge here,” Rickenmann said. “We’ve got a slow permitting process and high property taxes, so high that we’re competing against our neighbors. What do we do about that?”

Rickenmann’s proposed solutions, which more or less match the city’s tax study, include reducing selective tax breaks, primarily those on student housing, which can range from 35-50% over ten years.

Baddourah, a restaurateur, is also in favor of reducing selective tax breaks. He’s also in favor of eliminating the business license fee for businesses making less than $500,000 annually.

“[Eliminating the business license] is going to encourage small businesses to come in, and it’s not just the fee, which could be substantial,” Baddourah said. “A lot of small businesses don’t have the time to deal with the politics of a business license.”

A small business license in Columbia costs roughly $60 per year for businesses making under $25,000 per year, according to the city’s business licensing department, with an additional dollar added for each additional thousand dollars in revenue. By these metrics, a business making $500,000 yearly would pay an annual business license fee of roughly $530 annually.

Devine, owner of her own law firm, is focused on equity and inclusion in solving Columbia’s business woes. She plans to create a small business advisory council featuring workers from all sectors of Columbia’s economy, she said.

“There are so many people that aren’t getting to participate in the conversation right now. How are we supposed to fix our city’s issues if we don’t know those examples?” Devine asked.

This council would not only advise her and city officials on the state of small business in Columbia, but would expand the city’s official definition of “small business.”

“I went to see jazz last night on Main Street,” Devine said. “That musician, he’s a businessman. He should be treated no different than a brick and mortar establishment.”

The Columbia mayoral election and city council elections for District 1, District 4, and an at-large member are Nov. 2.

Tzima Brown started Sunrise Bath and Body Works in 2016 with help from a city grant. She says the city’s tax structure needs work.

Matthew Marcom, franchisee for Pelican’s SnoBalls, is the leader of Rosewood’s business corridor. He’s concerned that fledgling businesses may never leave the ground because of Columbia’s confusing regulations.