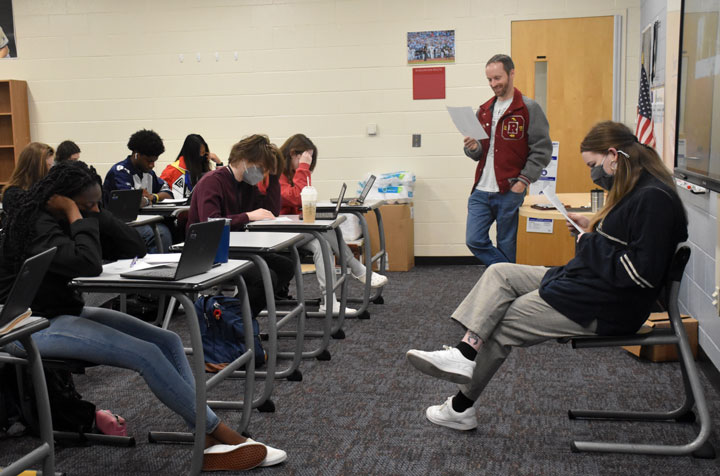

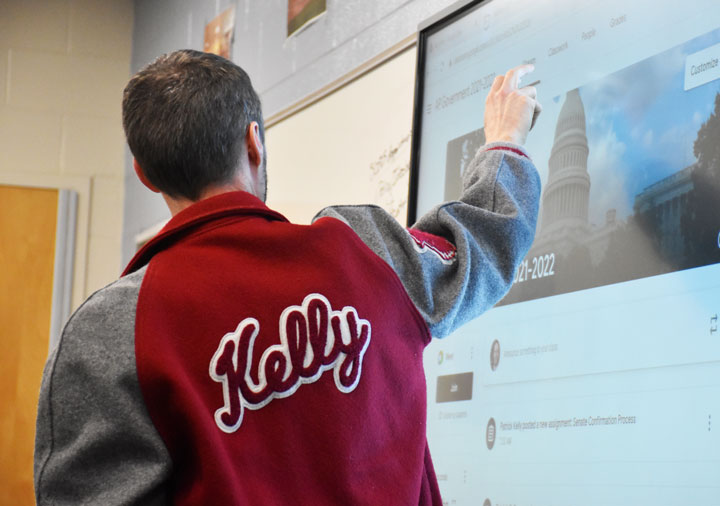

Teacher and lobbyist Patrick Kelly spends his afternoons at the State House, influencing education policies in South Carolina. Photos by Cora Stone

At 7:30 a.m., Patrick Kelly stands in front of his advanced placement government class, preparing to teach about policymaking and Supreme Court nominations. By 9:30 a.m., he is at the State House, advocating for South Carolina students and his colleagues amid an escalating education crisis in the state.

Kelly rises before dawn to teach, then races downtown from the Columbia suburbs to explain the complexities of curriculum and the classroom to lawmakers. Teachers and lawmakers say Kelly’s dual roles – as director of government affairs at the Palmetto State Teachers Association and part-time government teacher at Blythewood High School – make him an effective advocate and champion of educators and students alike.

“It gives me kind of a unique street cred over here that no other lobbyist has, because I’m the only one doing this,” Kelly, a former teaching ambassador fellow for the U.S. Department of Education and finalist for S.C. Teacher of the Year, said. “So when I sit down and talk to a legislator about this is what’s happening in schools, and this is what we need in terms of policy, it’s not just abstract.”

Facing burnout and a lack of support from legislators, teachers are leaving the profession at record-breaking numbers. Currently, S.C. educator vacancies are at an all-time high, with 1,121 open positions, according to a report released by the Center of Educator Recruitment, Retention, and Advancement, a nonprofit based out of Winthrop University that collects data and information regarding teacher retention.

State Sen. Mike Fanning, D-Great Falls, said South Carolina has had some of the least teacher-friendly legislation due to a lack of educators in the General Assembly and lawmakers’ failure to listen to teachers before creating bills.

“If we were going to change the way we build bridges in South Carolina, we would bring architects and road engineers to the table before we even draft the bill. We have never done that with teachers. We always come up with a bill and throw it to teachers,” Fanning, a former high school history teacher, said. “Patrick is helping change that conversation by not only splashing realism on bills, but subtly reminding us that we are in a teacher shortage and need incentives to bring teachers in and keep teachers in the profession.”

Fanning has known Kelly for seven years and is working with him to amend legislation that would allow some nonprofit organizations like the Boy Scouts of America and the Boys and Girls Club to advertise their programs, but only after school. He said that Kelly has credibility in the legislature because of his knowledge of teachers’ concerns.

“Unlike us, who may just see a teacher at church on Sunday, he is going to go back to school the next day and face the teachers who will hold him accountable,” Fanning said.

Richland School District 2 offers teachers a hybrid schedule, which allows Kelly to work for the PSTA and continue to teach at Blythewood, where he has been a teacher for 17 years.

He left his full-time teaching position and joined the PSTA when the pandemic turned teachers’ lives around in 2020. His decision was inspired by advice from his mentor and former U.S. Secretary of Education John King.

“He shared that he left the classroom when the satisfaction that he gained from day-to-day teaching was outweighed by the frustration he saw with what was happening to students in the profession beyond the four walls of his classroom,” Kelly said. “And I think that’s kind of where I was at in 2020. I felt like there was a need to do some work beyond just my classroom.”

The Tennessee native moved to South Carolina to attend the University of South Carolina, where he originally planned to go into law. After realizing his passion was in the classroom, he changed paths and pursued education. Kelly, 41, met his wife at UofSC and decided to stay. They now have two children who are students in Richland School District 2, which makes Kelly’s fight for quality education even more personal.

To deal with the stress of his positions, Kelly runs in his free time, but dedicates as much time as he can to his wife and children. Kelly said that being a husband and dad are the most important hats he wears.

According to Kathy Maness, executive director of Palmetto State Teachers Association, hiring Kelly was one of the best decisions she has made. He has built bipartisan relationships and been effective in shaping complex legislation, she said.

“Not only is he good at what he does, but he’s extremely smart when it comes to policy,” Maness said. “Another one of our staff people said the other day that he’s probably the smartest education lobbyist in the country. I would put him up against any of them, and he would excel.”

As a lobbyist, Kelly’s main focus has been teacher recruitment and retention, but he has also pushed for student mental health resources in a crisis that has been exacerbated by the pandemic. Additionally, he responds to controversial education issues such as recent legislation aiming to restrict the teaching of critical race theory, which is the study of the intersection between race and law in American history and politics.

“He talks the talk and walks the walk. And that’s what he’s doing,” Maness said.

Kelly’s ability to influence legislators was sharpened after working under two Presidents, Barack Obama and Donald Trump, at the Department of Education as the lead Washington Teaching Ambassador Fellow in 2016.

Kelly still has his hand in national politics through the National Assessment Governing Board, where he is a member and advocates for South Carolina on a federal level. The governing board determines the amount of federal Title 1 dollars a state receives through the only test given at a national level, the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Title 1 is the largest federal aid program for public schools and provides federal funds based on student enrollment, the free and reduced lunch percentage, and informative data such as the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

“When they’re talking about testing, I’m able to give a pretty unique perspective of, ‘Hey, guys, I’m actually helping with the oversight of the big testing program. Here’s what that could mean for South Carolina,’” Kelly said.

Lisa Ellis, founder of educator advocacy group SC for Ed and a fellow teacher at Blythewood High School, said that Kelly is “the teacher that we want to keep in the classroom” while the state is in crisis because of his effectiveness in the legislature.

“He just has a way with talking to them,” Ellis said. “He just gets them to push the envelope a little bit farther because he sees what is going on in the schools.”

Through the chaos of balancing his multiple roles, seeing students recognize their full potential is what keeps Kelly going.

“You have those ‘aha’ moments on a day-to-day basis, where a student figures out a complex problem, or a student writes a really good essay, and you’re able to give them that feedback. So, you’re seeing a student really grasp, not just that they’re talented, but they’re talented beyond what they gave themselves credit for, and I don’t know that there’s another profession that really gives you an opportunity to do that,” Kelly said.

Kelly’s government students role-play Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts’ confirmation hearings while they learn about the confirmation process of the high court.

Blythewood High School offers teachers a hybrid schedule, which allows them to work multiple positions within the school.

On “90’s Day” of Blythewood High School’s spirit week, Kelly sports his cross country letterman jacket from when he was a high school athlete in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.