The British Bulldog Pub is an English-owned business in Columbia. It represents one of many ways Brexit is tied to the U.S.

By Hayden Blakeney and Caroline Cherry

Around the Christmas dinner table in his small British town, Kieran Smith experienced the common generational dilemma that transcends borders. Only this time, it’s over a real border.

“I sit around the Christmas table and my Gran will make a joke [about it] and I will just be eating my food and be like ‘Hmm,’” said Smith with a chuckle.

Smith is a political science student studying abroad at UofSC from Bedford in the United Kingdom, and like over 80% of young people, he wants the U.K. to remain in the European Union.

“There’s a whole load of issues for a young person, I found it very hard to understand those who voted leave, especially in my generation,” Smith said.

As with most polarizing political topics, his differing opinion has led to discourse over holiday dinners and fights with family members.

“This divided my family in a way that I didn’t think was possible.”

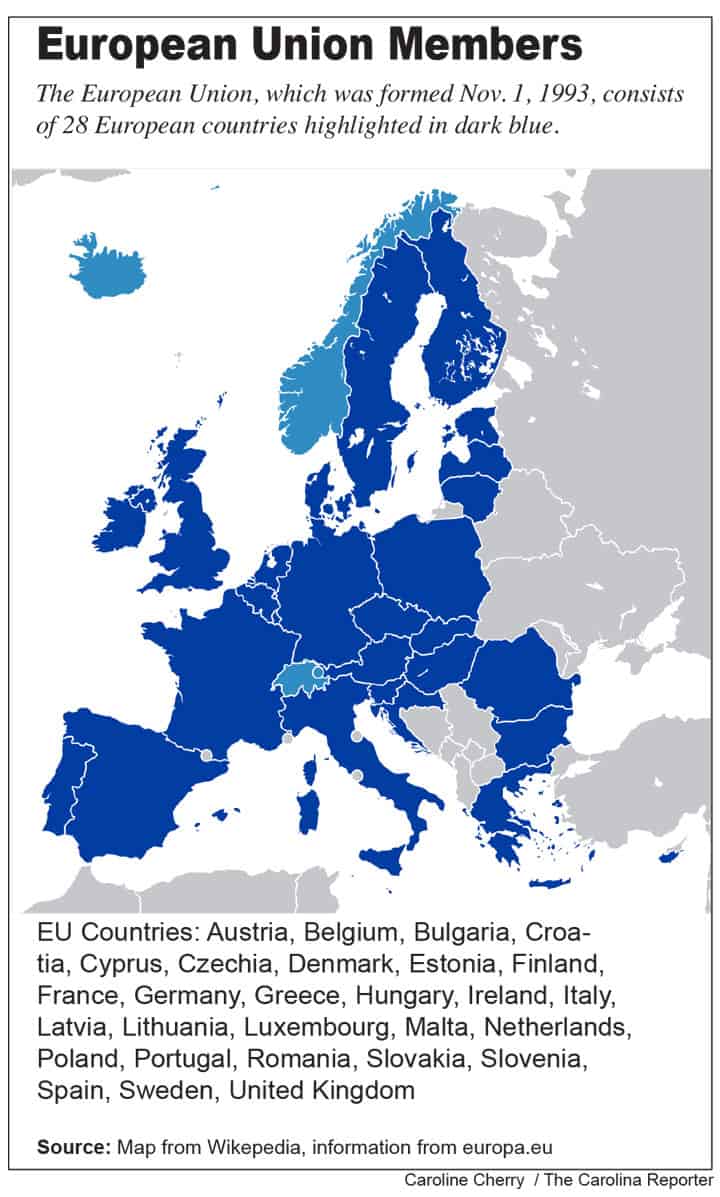

“Brexit,” a term for the U.K.’s departure from the European Union, has been a source of contention since the country’s 2016 referendum, the popular vote open to all U.K. citizens that initiated the exit.

“Every single person that I knew had an opinion on it,” Smith said. “I didn’t find many people that sat back and were like ‘Oh, I don’t really care.’”

Smith’s first time voting was in the 2016 referendum. Although he said he was originally on the fence, Smith’s position has only become more concrete over the past three years. Due to his belief that the EU is economically beneficial for his country and his appreciation for the ease of travel in the Eurozone, Smith voted “remain.”

“Leavers,” those who want the U.K. to leave the EU, often paint the departure as “taking back the country” from the EU’s regulations. Older leavers compare Brexit to the U.K.’s self-sufficient past in the wake of World War II shortages, but Smith said the country’s economy has drastically changed.

“Back then most of our meat was produced in the U.K., most of our milk was produced in the U.K., but now we have stuff from New Zealand and American and the European Union massively. It scares me a lot,” Smith said. “The point is, we cannot survive on our own like we did 50 years ago.”

Although Brexit could free the U.K. from EU regulations on food products and banking, it could have very negative repercussions for the country’s economy.

Mark Bowyer, owner of The British Bulldog Pub in Columbia, moved to America 26 years ago from the U.K. He shows no concern over possible dealings between America and the U.K., but is still not in favor of the U.K. leaving.

Bowyer is from Liverpool, U.K., a city that almost unanimously voted to remain. The unexpected support from the traditionally labor-party city comes after years of reinforcement from Europe when their own government decided to ‘let Liverpool decline.’

“A lot of the big cities, Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle, under the [Margaret] Thatcher years especially, were abandoned by the government,” Boywer said. “But the Europeans started putting, especially into Liverpool, millions and billions of pound and revitalizing the whole city.”

A loyalty developed and has continued to endure.

The most recent plan proposed by Prime Minister Boris Johnson was approved by the EU, but is not likely to pass Parliament. This is the last-ditch effort before a no-deal Brexit, which means the country would leave the Eurozone with no trade deals or ability for EU citizens to travel, study and work seamlessly. The final deadline before a no-deal Brexit is midnight Oct. 31.

In a global economy, it is nearly impossible for one country’s problems to stay in its own borders. This could negatively affect trade with the U.S. and have a rippling effect on the U.S. economy.

One possible outcome drafted by the British government in the case of a no-deal Brexit, called “Operation Yellowhammer,” recommends the stocking of food and drugs in anticipation of shortages. Another plan, “Operation Redfold,” calls for military involvement in case of civil unrest.

“The fact that the United Kingdom, Great Britain, is talking about stockpiling food and medicine. Imagine if the U.S. was talking about it,” Smith said, shaking his head in disbelief. “That’s what you would expect from North Korea.”

Another hypothesized outcome of a no-deal Brexit is the creation of a hard border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, which has been a part of the U.K. since 1922.

While the U.K. is still in the EU, Northern Ireland shares what is called a “soft border” with Ireland, similar to the border between two American states. Similar to the U.S., families can be scattered throughout both sides, working and living in Northern Ireland and the Irish Republic.

“I’m half Irish and my family are Irish Catholics that have always been in favor of a united Ireland,” Smith said. “For there to be a hard border … I don’t want to think about it.”

A hard border would separate families and violate a major condition of the Good Friday Agreement that ended the late 20th century border war known as the Troubles, a decades-long conflict between Irish Catholics that want a unified republic and Protestants that want Northern Ireland to stay in the U.K. If a hard border emerges, that violence could continue. Last April, a journalist name Lyra McKee was killed in Northern Ireland during a riot about the Irish partition.

Even though the Irish border is an ocean away, the effect of a hard border might be felt in America.

“Americans have also been connected to Ireland in a weird way,”Alex Kroll, the president of the USC Irish Club, said. “America sees in Ireland a younger version of itself, of revolution under British rule, that you have a guerilla war that you need to end and peace afterward.”

He noted the importance of the U.S.’s mediator role during the Troubles and the worry that it could be repeated if a hard border is made.

“America, in the past 20 to 30 years, has been a major player in establishing that peace, negotiating the Good Friday agreements,” Kroll said. “It would be nice to see America step in if a Brexit happens and negotiate and find an end to that conflict.”

Although a hard Brexit could be in the near future, for young people like Smith, an end to conflict seems far away.

“If you compare the divide in families here over Trump and the one over Brexit, with Brexit it’s not done,” Smith said. “It just keeps going on and on and on.”

Kieran Smith from Bedford in the United Kingdom said Brexit will do economic harm to his country. “We cannot survive on our own like we did 50 years ago.”

This is the first page of Boris Johnson’s Brexit plan that is unlikely to pass Parliament before the Oct. 31 deadline.

Alex Kroll, president of UofSC’s Irish Club, is worried about the possibility of a hard border in Ireland. “America has always been connected to Ireland in a weird way.”