The chief of the Catawba Indian Nation in Rock Hill poses this philosophical question to visitors: “What does Catawba look like in modern day?”

William “Bill” Harris wants people to envision the role that his people and its ancient culture should play in the world today.

The Catawba Indian Nation has been in the upper region of South Carolina, by most estimates, between 4,000 and 6,000 years.

“Recently we found out that they’ve found some pottery that dates back 8,000 years, so they actually think we’ve been in this region a little bit longer,” Cassidy Plyler, the craft store manager of the Catawba Cultural Center, said.

The Catawba’s lengthy history in the region demonstrates how a people can weather the sands of time.

But the world has changed.

As cultural assimilation and globalization push toward a unified culture, where does that leave a unique people such as the Catawba?

The Catawba suffered many blows to their population in the early decades of the United States, ranging from smallpox epidemics to voluntary emigration to join the Cherokee and Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

Since the last half of the century, Catawba leadership has worked tirelessly to reinforce the culture of the tribe with its estimated 3,000 remaining members.

The Catawba recently celebrated 25 years of federal recognition. It’s a status that would have come a century sooner had the state of South Carolina not entered an illegal treaty with them in 1840.

The first Article in the United States Constitution establishes that all treaties with any party – foreign or domestic – need to be conducted through the federal government or, at the very least, approved by Congress. South Carolina bypassed this law and drafted its own treaty with the Catawba, barring them from becoming federally recognized and receiving federal funding until the treaty was nullified.

Because of a slew of other national crises that took higher priority with the United States Congress, the Catawba did not receive their federal recognition until a century and a half later.

However, this was not without loss of cultural identity. Historically, the tribe sacrificed its native tongue to adapt and adopt English in an effort to better relations with the early American settlers.

But a dead language does not have to stay in the grave.

Centuries later, it’s being revived and taught to Catawban youth in the reservation’s school.

“I think we are sort of, as I say, renaissance – bringing it back,”Harris said. “There will come a time when it will be a first language brought back to be a second language. Ours is not so much a written language as it is a recorded language, oral.”

The Nation thrives in the realm of pottery, an iconic and important tradition that has stood the test of time. The area that the Catawba inhabits is rich in clay soil, the primary art supply for the elegant pottery found in the Catawban Cultural Center.

“The thing that is unique to us, especially on the Eastern seaboard, is that we have 4,000 years of it without a generational stop,” Harris said.

Harris believes that preserving the past is of the utmost importance for Catawban survival. He said that trying to adapt and homogenize with the world will only set his culture up for inevitable disappearance.

“If we do not embrace what got us here and build off of that, we will truly doom ourselves,” Harris said.

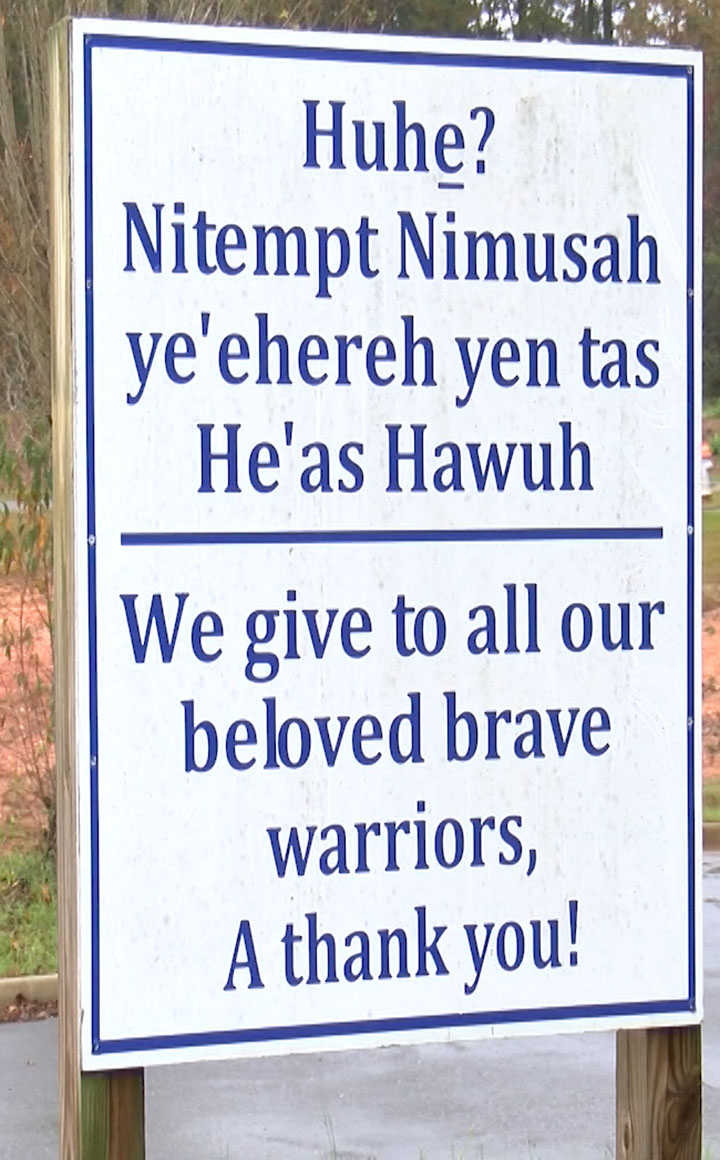

The home of the Catawba features many signs displaying the written Catawba language. Immersion in the language helps young members of the Catawba Nation pick up the language and perpetuate it.

Pottery has become the unofficial icon of the Catawba Nation. Chief Harris says his tribe has had 4,000 years of continuous practice with pottery.

The Catawba Indian Reservation sits just outside of Rock Hill, SC. It’s nestled among clay pits, which is responsible for the Catawba’s historical love of pottery.