Electric cars, like this one at a charging station, reduce emissions. (Photo by Lauren Larsen/Carolina News and Reporter)

Columbia is making progress toward incorporating more clean energy initiatives throughout the city one step at a time, starting with energy audits.

Energy audits help identify how much energy a building uses, and ways to improve building efficiency and change non-renewable energy sources to renewable ones.

“If we’re buying a building, now we’re going to make sure it has that capacity. So that way if we want to go solar we can do it very, very easily,”said Mary Pat Baldauf, the city’s sustainability facilitator.

Columbia is working toward having 25% of city-owned investments and infrastructure audited by 2025, 50% by 2028 and 100% by 2036.

The audits will be funded through the city and ideally save taxpayers money by saving energy usage.

But as with many cities, clean energy goals are difficult to achieve unilaterally because Columbia is not a producer of energy. Dominion Energy is the exclusive provider for city residents. The switch to clean energy also is expensive, and Columbia is home to a higher number of tax-free entities. That kind of small tax base keeps some innovations from happening as quickly as the city would like.

The city is “just kind of at the mercy of what Dominion does,” said Conor Harrison, associate professor with the University of South Carolina’s College of Arts and Sciences. “So if Dominion decides that they want to build a new gas plant, which is what they’re trying to do, you know, Columbia is always going to be buying whatever it is that Dominion is pumping out onto the grid.”

Dominion’s energy comes from a combination of old coal burning plants, gas fired power plants, some nuclear and a few renewables right now, said Bob Petrulis, chair of Columbia’s Climate Action Protection Committee (CPAC). He said he hopes the city can encourage Dominion to retire their coal plants and develop renewable sources, but they’re hesitant to phase out plants that are still productive.

“I think we’re really going to have to work with them and negotiate with them about improving their portfolio,” Petrulis said.

Dominion did not immediately respond to a request for an interview.

City setbacks

Columbia’s role as a capital city sometimes makes innovation a slow process.

Columbia’s tax base is lower than that of many cities because of the large number of government and nonprofit entities that don’t pay taxes, such as state government and a handful of universities.

“We don’t want taxpayers to end up holding the bag for huge amounts of money that aren’t necessary,” Petrulis said.

The City Council has not yet approved money for the energy audits. And the city does not know how much the total cost of the audits.

The city plans to pay for the energy audits by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the city’s general fund or a performance contract, Baldauf said.

The IRA is an initiative put in place by the Biden administration partly to address climate and energy needs, environmental justice and the country’s position in domestic clean energy manufacturing. The IRA offers monthly grants that the city hopes to take advantage of, Baldauf said.

Another option is paying for the audits from the city’s general fund, which would have to be approved by City Council.

Lastly, the city could pay for the audits based on money it saves from the clean-energy improvements, an after-the-matter option but a feasible one, Baldauf said.

The city also doesn’t yet know who it would hire to complete the energy audits.

The city is using requests for qualifications for the work, which will help establish a group of organizations that could do the work.

Expertise and cost will be considered when selecting a company or companies, Baldauf said.

Clean energy, also known as renewable energy, doesn’t use fossil fuels or emit greenhouse gasses like CO2, methane and pollutants into the atmosphere.

Burning fossil fuels has created a significant change in the earth’s atmospheric composition, which scientists have said drives climate change.

Reducing gas emissions is good for the economy and the city as it reduces pollution and saves natural resources, Baldauf said.

The most common renewable energy sources are solar, wind and hydro. Nuclear energy is more controversial because, although low carbon emitting, it creates nuclear waste.

City progress

Columbia, despite the limitations of municipal government, is looking to solve energy issues at the city level.

In short, it wants to be a leader.

USC held a conference in 2022 called Climate Ready Columbia to address the climate crisis and look for solutions at the municipal level.

The city of Columbia, CPAC, the Sierra Club and many other local environmental and energy related organizations and companies were partners in and panelists at the event. CPAC is a citizen advisory committee appointed by City Council responsible for providing advice to the city on climate and environment-related issues.

The Sierra Club, a national nonprofit environmental club, talked about its initiative called “Ready for 100” to get cities to pledge to decarbonize their energy usage by a certain date.

Columbia and its previous mayor, Steve Benjamin, signed the pledge five years earlier, in 2017, to commit to using 100% renewable energy by 2036. More than 125 other cities signed the pledge.

“We’re just beginning to see that implementation happen, but we have some really good people in the city staff who are very committed to doing this,” Petrulis said.

In the past few years, CPAC worked on a second resolution to establish a timeframe and benchmark goals. The first resolution was about why the city was implementing these new goals, while the second was about how the goals will be reached. Before the second resolution was developed, there were very few plans and procedures in place.

While the “Ready for 100″ campaign has come to an end, many cities continue to reach milestones closer to 100% clean energy.

Another goal Columbia set was reaching up to 75 megawatts of renewable energy by the 2036 deadline, which would power all of the city’s operations.

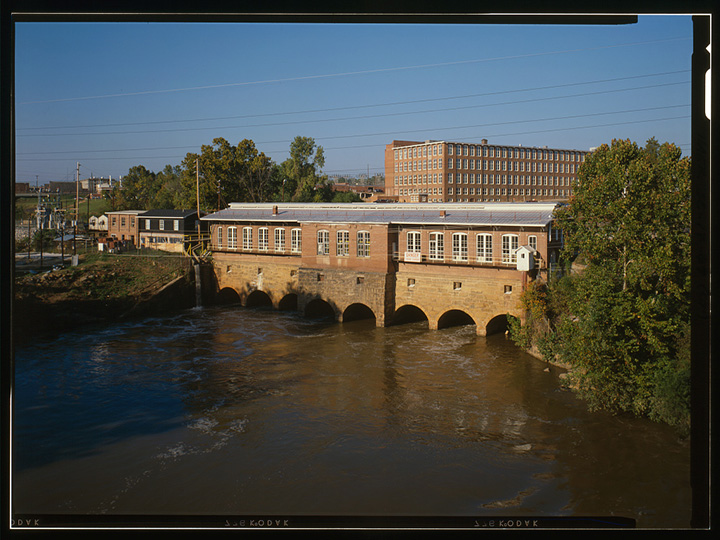

The Columbia Canal in downtown is home to a hydroelectric dam that hasn’t been used since widespread flooding in 2015. It produces around five megawatts of clean energy, however, and the city is working to get it running again.

Petrulis said when running again it could be used to power the water plant next door or somewhere within the city’s grid.

Looking forward, the city hopes to be granted an EPA grant after applying for $10 million to help implement more solar energy.

The city is also in the process of making a public online dashboard in the next year to show progress in these different initiatives. The plan is to update it monthly.

Looking forward

Despite these new initiatives and progress, there are setbacks.

The city also has relationships with the state and federal government, the county, and other municipalities, which makes reaching goals toward clean energy difficult, Petrulis said.

For example, when reaching goals toward complete clean energy, the Comet bus system would have to change over to electric vehicles. But the Comet system runs buses all over the region and not just in Columbia, Petrulis said.

Still, it’s good to try, Harrison said.

“I like that the city is ambitious and trying to do this,” he said. “I think the problem is just the market that we exist in makes it really, really difficult to do things that are too ambitious.”

Also, although the state could intervene, government officials traditionally let major utility companies tell them what to do, Harrison said.

But William Lamb, board chair for Sustainable Midlands, said he hopes legislators will continue to make energy solutions a higher priority in the future.

“If we’re going to run the world on clean energy, we have to have vehicles and home appliances and things like that — that can run on clean energy, ” Lamb said.

Lamb said electric vehicles might come with pushback because of the cost to figure out charging and maintenance.

The federal government has a program called the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI), as a part of the Inflation Reduction Act. While the program supports electric vehicle charging infrastructure, the money goes to states rather than cities.

But it’s also good to get residents involved, Lamb said.

Besides having an electric vehicle, community members can reduce their carbon footprint by composting, recycling and installing energy efficient upgrades at home, such as LED light bulbs or insulation in the attic.

Residents also can lobby the Public Service Commission, the state’s regulatory body for energy production, said Matt Kisner, a USC professor and creator and director of the “Climate Ready Columbia” conference.

Besides reducing greenhouse gasses, people also have to adapt to a warming world, Kisner said.

“Even if we can’t change our energy production at all, and we keep emitting lots of greenhouse gasses here in the city, we’re still going to have a city that’s getting hotter, and a city that’s more prone to flooding,” Kisner said. “And so, we need to be adapting and changing the way that we do our infrastructure.”

Petrulis said he feels positive because of people, including Mayor Daniel Rickenmann are to trying out new ideas to engage business in climate related efforts. Rickenmann is also a member of the Smart Surfaces Coalition, whose goal is to reduce the amount of heat absorbed on city surfaces.

“I think we’ve made some pretty good progress,” Petrulis said of the past two years. “And we’ve got a long way to go.”

Solar farms are becoming popular in the South because of the region’s sunny weather. (Photo courtesy of sc.gov/Carolina News and Reporter)

Columbia’s former hydroelectric dam once produced renewable energy. (Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress/Carolina News and Reporter)

Recycling cans in city neighborhoods help recyclable products stay out of landfills. (Photo by Lauren Larsen/Carolina News and Reporter)

Members of the city’s Climate Protection Action Committee discuss energy-saving solutions to suggest to city government. (Photo by Lauren Larsen/Carolina News and Reporter)