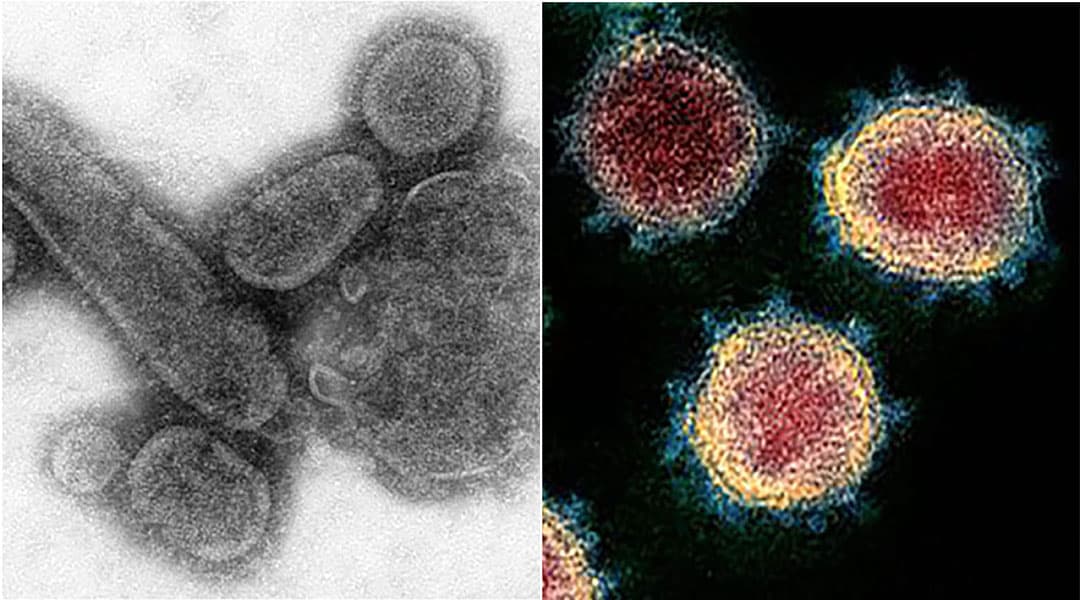

Cells of 1918 influenza, left, and COVID-19 disease cells. Credit: Center for Disease Control.

The streets were empty, but the hospitals were full.

Americans were weathering a worldwide pandemic at home and a world war abroad. Theaters, schools and churches were all closed as world governments called for a state of emergency. Anyone who dared go into public was recommended to wear a face mask, if they could find one.

In 1918, the country was gripped by a virus – the Spanish influenza. For many, it feels like the same story 100 years later with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite the seemingly similar circumstances, the two pandemics are different illnesses being battled in different eras.

“This virus is not SARS, it’s not MERS, and it’s not influenza. It is a unique virus with unique characteristics,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus explained in a March 3 press conference.

A century after the 1918 pandemic there are still misconceptions about the disease, including its name.

Experts no longer believe the Spanish flu originated in Spain. The source of the name came from neutral Spain being able to report on the disease without wartime censorship.

“The 1918 flu pandemic actually most likely originated on a pig farm in Kansas,” said Sharon DeWitte, a bioarchaeologist and professor at the University of South Carolina. She focuses on historical health and disease.

The pandemic began as World War I ended in 1918 and infected a third of the world’s population within two years. The influenza killed an estimated 50 million people.

COVID-19 was discovered in an animal market in Wuhan, China. The name originates from its discovery in late 2019. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization classified the outbreak as a pandemic. WHO explained that COVID-19 is the newest strain of coronavirus, a type of virus known to cause respiratory infections. It was believed to begin in bats.

Ghebreyesus said both diseases cause respiratory disease and spread the same way.

While both diseases are deadly, influenza affected mostly healthy adults, but had a higher mortality rate in children and the elderly. The fatality rate hovered around 2%.

“It had a really interesting and alarming mortality profile,” Dewiite said. “The 1918 flu produced a W-shaped mortality profile: high numbers of deaths of infants and the elderly and a peak of deaths for young adults.”

Comparatively, COVID-19 has been reported to more greatly affect older adults. According to New York City Health, more than 70% of deaths have been in adults above the age of 65. Unlike with many diseases, children been mostly unaffected.

Ghebreyesus said that despite the fact COVID-19 is a more severe disease, it does not spread as easily as influenza.

According to John Hopkins, COVID-19’s mortality rate is around 4.9% across the U.S. This number has and will continue to change as the pandemic evolves.

By the end of the 1918 influenza pandemic more than 50,00 South Carolinians were infected with influenza and 14,250 died. As of April 20, South Carolina had 4,264 COVID cases and 119 deaths.

Despite increased population and world travel in 2020, COVID-19 is not expected to lead to influenza-level fatalities.

Then, aspirin was the primary medicine taken to fight the disease. Antibiotics and antiviral medications were not yet available. Today, scientists and doctors across the world are using cutting-edge technology to fight the coronavirus. Better hygiene and nutrition also improved the population’s health.

Dewitte said that despite the diseases’ differences, doctors can learn a lot from pandemics of the past.

She said the biggest lesson to be learned from the 1918 pandemic is the importance of social distancing.

“Social distancing can be effective in slowing the spread of the disease, but we can’t be impatient and relax social distancing measures too soon. We really need to think about the long term greater good.”