A part-time job fair, held by the Career Center at UofSC at the beginning of the semester, had 38 employers and 716 students attend, which has been one of the highest attendance rates they have seen since 2016. Photo by Ashton Van Ness

From juggling homework and exams to keeping up with friends and dealing with post-graduation job searches, college students face a whole slew of stressors. Adding a job to the mix can seem like an impossible task, but it’s something many students do to pay for tuition or earn extra money for living expenses.

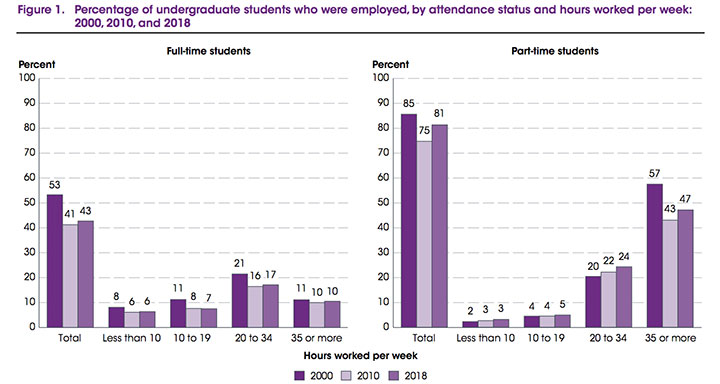

The National Center for Education Statistics found that in 2018, 43% of full-time undergraduate students were employed along with 81% of part-time undergraduate students. They classified full-time students as students taking at least 12 hours of classes, which is typically four classes per semester.

Experts debate whether working has a positive or negative effect on student academic performance, with some suggesting too many working hours might bring down a student’s grade point average. But several studies found students who work average hours are better time managers and have slightly higher GPAs than students who do not work at all.

Lauren Barbieri, a fourth-year marketing major at the University of South Carolina, serves and bartends at Publico in Five Points.

“I work about 30 hours a week. I literally made my class schedule to work with my shifts,” Barbieri said. “I’m taking four classes and one of them is online and asynchronous. I also don’t have Friday classes and on Monday and Wednesday I only have one class.”

Having the ability to create a class schedule around shifts she wants to work is something Barbieri said has significantly helped her manage her class assignments while maximizing the hours she can work.

“I will say sometimes it’s hard. If I have a test the next day and I’m closing at work I can’t leave or call out because I’ll get in trouble, so I have to work my shifts and stay up late or get up early to study, which can get really annoying,” she said.

Choosing to work on campus or finding a job that offers flexibility, especially during exam weeks, can be vital to finding a way to balance responsibilities.

“There are so many people that work at Publico and most of them are students, so people switch shifts and help each other out all the time,” Barbieri said. “I bartend Wednesday mornings and I have class at 3:55 p.m. but the shift is supposed to end at 4 p.m., so I have the evening shift bartender come in 30 minutes early so I can leave and go straight to class.”

Barbieri, who will graduate in December a semester ahead of schedule, has been able to work 30 hours per week and successfully stay on top of her academic assignments. But, most experts suggest full-time undergraduate students should not work more than 20 hours per week. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, only 10% of full-time undergraduate students worked 35 hours or more per week in 2018.

Mark Anthony, the senior associate director of the Career Center at UofSC, said the center recommends students with full course loads not work more than 20 hours per week as it can be harmful to a student’s academic progress.

However, it is suggested students work part-time with a maximum of 15 hours per week as studies have found this enhances time management skills and academic performance compared to students who do not work at all.

Mike Burns, Director of LifeWorks Operations and Analytics at Berry College, wrote a paper that analyzed studies and discussed how student work affects academic performance and post-graduate employment. In his paper, Burns concluded that research supports the hypothesis that students who work average hours tend to have slightly higher GPAs than students who do not work at all.

A 2007 study by Lauren Dundes and Jeff Marx was conducted at a liberal arts college in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. They found undergraduate students who worked between 10 and 19 hours per week had higher GPAs than students who worked less than 10 hours per week or more than 19 hours per week.

A more recent study published in 2012 by Brandon K. Lang used data from the National Survey of Student Engagement to find the effects of jobs on student performance. This study also took participation in extra-curricular and social activities into account.

Lang found that undergraduate students who work have slightly higher GPAs than students who do not work and that time spent on social activities was lower for working students, especially for students who held jobs off-campus. When comparing grades of students who work on-campus versus off-campus, Lang found students working on-campus had slightly higher grades than those working off-campus.

Burns analyzed many other studies in his paper but the results from almost all of them were the same: average hours of student employment has a positive impact on grades.

Of course, not all situations are the same. These studies have found that typically students who work between 10 and 19 hours a week tend to have slightly higher GPAs, but a struggling student working a few hours a week would probably not be benefitted from adding more hours to their plate.

Each student is different and how many hours they can handle while still maintaining a strong academic record differs as well.

Kelly Packer, a third-year finance and economics major at the University of South Carolina, chooses to work at Barre3 only around 10 hours per week, and this decision is mostly in part to her demanding extracurriculars.

As president of her sorority, Packer said the list of responsibilities that come with the title are never-ending.

“I would say I could easily put 100 hours of work into sorority stuff a week,” she said. “If anybody needs anything I’m the person they call. If there’s something going on in a week I have a big test or project, it’s hard to get done because I’m in meetings all day.”

However, she said the few hours she works per week at Barre3 don’t negatively impact her schoolwork.

“My job doesn’t take away from school too much at all, it’s more the president thing,” Packer said. “It works out because all my classes this semester are in the afternoon and I work at Barre3 from 7 a.m.-11 a.m. some days or 10 a.m-2 p.m. and I don’t have to work evenings.”

When asked if she had any tips she would give to fellow students who have stretched themselves to be involved in as many areas as she had, Packer’s top recommendation was to budget time well and fully dedicate yourself to whatever you are doing at each moment.

“I try to put myself in different settings so they don’t overlap,” Packer said. “When I need to do schoolwork, I turn my phone on airplane mode and I don’t do any sorority stuff. I do schoolwork at the library, I do (Pi Beta Phi) work at the house, and when I work I obviously go to my job.”

“I’m making enough money with those hours though,” she added. “It’s really nice, it’s just like extra spending money.”

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is part of the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences. They focus on the collection and analysis of education data in the United States. Graph courtesy of NCES.

One thing UofSC student Lauren Barbieri said helps her manage her time with classes and her job is that all of her classes are at UofSC’s school of business which is only a three-minute walk from her apartment at 650 Lincoln. Photo courtesy of Lauren Barbieri

UofSC student Kelly Packer, pictured at her sorority’s 2021 bid day, said she works 10 hours a week at both the downtown and Lake Murray location of Barre3. Photo courtesy of Kelly Packer