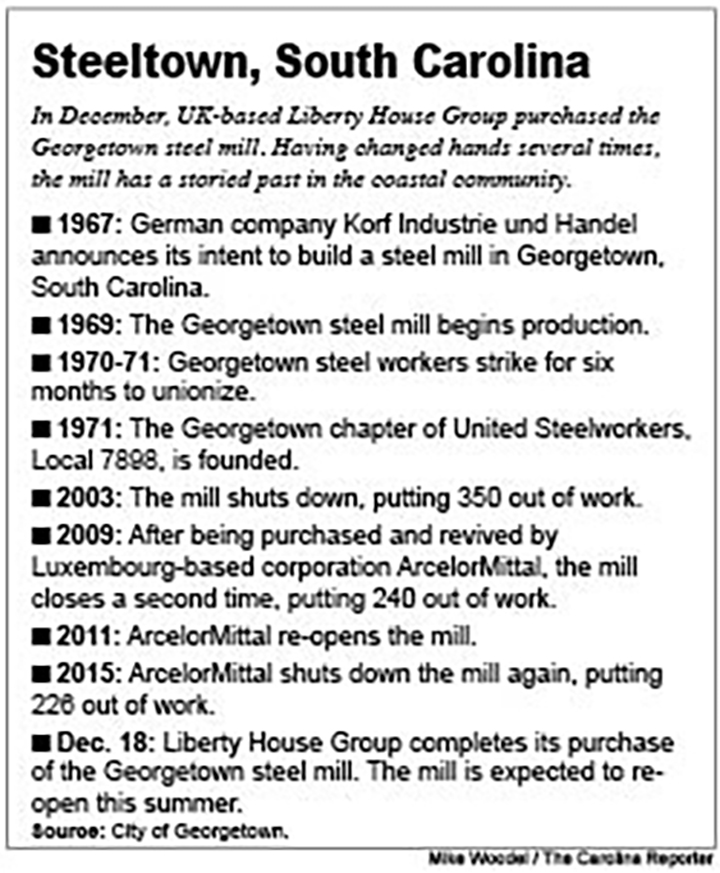

United Steelworkers of America Local 7898 was founded in Georgetown in 1971 following a six-month strike by workers at the local steel mill. Cheap steel imports are largely to blame for the mill’s three closings since 2003, says Local 7898 president James Sanderson.

James Sanderson was elected president of Georgetown’s USWA Local 7898 three decades ago. He is hopeful that federal tariffs on foreign steel will protect American steel manufacturers.

Under new ownership and only a year separated from its 50th birthday, the Georgetown steel mill is expected to resume production this summer according to Sanderson.

Georgetown resident Melvin Cohen has worked at the local steel mill since 1973. He plans to return to work to train new workers when the mill is re-opened by British company Liberty House Group.

GEORGETOWN – As a union man, James Sanderson represents a faith in organized labor unshakeable as steel.

Sanderson has held the presidency of United Steelworkers of America Local 7898 in Georgetown, South Carolina, since 1988, supervising union members as they rode out three closures of the local steel mill. All of these closures, he said, have been forced by imports of cheap foreign steel.

But the mill’s purchase in December by London-based Liberty House Group and impending re-opening take on a different optimism with the Trump administration’s 25 percent tariff on steel imports from all countries excepting Canada and Mexico.

“It will definitely be beneficial to our plant, Liberty, and it would be beneficial to all of the people who work for a living in the United States of America,” Sanderson said. “There’s no doubt in my mind, 100 percent, that the tariffs that Donald Trump announced and, hopefully… are implemented will be a shot in the arm for all the industries in this country.”

Despite Sanderson’s enthusiasm, the tariffs and South Carolina’s role as a manufacturer of cars for foreign companies could still put the state in a precarious position. BMW employs 9,000 workers at its factory in Greer, and construction is underway on a Mercedes-Benz van factory in North Charleston and a Volvo factory in Berkeley County.

At the Geneva Motor Show in March, BMW CEO Harald Krüger said tariffs would affect his company’s hiring of American workers.

Speaking before the state Senate on March 13, S.C. Commerce Department Secretary Bobby Hitt warned lawmakers of the impact obstacles to a free market might have.

“Uncertainty always brings concern in business,” Hitt was quoted in The State.

Steel is a crucial byproduct of Georgetown doing business. Perched on the near northern half of South Carolina’s Atlantic coast, the city holds a population of 9,000 and a spot in the census-designated Myrtle Beach metropolitan area. Its economy makes it an outlier on the Grand Strand, a seaside, industrial city in a region built on tourism. There are no cloudless days, as the stacks rising from the International Paper plant just off downtown belch white clouds into the sky even on clear spring afternoons.

Standing at the intersection of Hazard and Butts streets in Georgetown, USWA Local 7898 is decorated as a shrine to past union successes. On a wall behind a raised stage, a plaque presented to Sanderson holds gavels used by USWA presidents to open three national conventions – next to it, framed photos of Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton.

Outside Sanderson’s office hangs a framed copy of the October 13, 1967, Georgetown Times – a special edition announcing Korf Industrie und Handel’s intent to build the mill that now sits, vacant but waiting, along South Fraser Street with its back to Winyah Bay.

As an ardent support of the Trump tariffs, Sanderson has seen the effect an influx of cheap steel can have on American manufacturing. Following a previous closure, the U.S. Department of Labor found that mill workers qualified for Trade Adjustment Assistance. The TAA is a program established by the Trade Act of 1974 to provide aid to workers whose employment status is directly affected by imports.

This in mind, Sanderson has much to say on the topic of American companies with foreign interests.

“Look at the businesses in this country that have business interests overseas,” Sanderson said. “If the media was to try to do an analysis of all the companies in this country that have… all kind of interests in these other countries, then they will be able to connect the dots and realize why they are so against these tariffs. Because they are over there making money on the backs of the American people. They’re not investing in America.”

Sanderson also railed against American companies’ use of cheap labor overseas while steelworkers in his own union approach the end of their third mill closing since 2003.

“They’ve been over there in these other countries exploiting children, labor laws; they don’t have no OSHA standards over there, they don’t have no environmental laws, they don’t have no wage laws over there,” Sanderson said. “How can you compete with that?”

The stepson of an International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Ship Builders, Blacksmiths, Forgers and Helpers member, Sanderson came to the Georgetown mill in 1974 to work as an electrician. Though his USWA position is full-time, he also spent 13 years as a training coordinator with the mill’s Institute for Career Development until his layoff by previous mill owner ArcelorMittal in December 2017.

Local 7898 also has members organized at the International Paper plant, two local nursing homes and Georgetown Memorial Hospital. Sanderson forecasts a growth of 250 workers when the mill begins rolling steel again, which could be as early as this summer. If correct, this would double the local’s current membership.

Of Liberty House Group, Sanderson said there is no sign the tariffs affect the deal finalized in December. He also adds that LHG’s intent is not to use the mill as an exporter to the UK, but to keep the mill’s products domestic.

“They’re here for the long haul,” Sanderson said. “They want to use this as a stepping stone for building a much bigger footprint in this country.”

Before the mill shut down in August 2015, Sanderson said, the steel rolled by the mill was shipped to companies in Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky and Indiana.

In addition to the tariffs, Sanderson is always open to talk about 7898. He and his financial secretary, Latonia Green, both find members of their local to be faithful, staying on even through three closings of the mill in the past 15 years. But the union hall still can seem almost lost in deep-red, right-to-work South Carolina.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 78,000 of South Carolina’s nearly 2 million workers were represented by a union in 2017. Of those 78,000, only two-thirds were union members. As a percentage of total workers, the state ranks dead last in the nation in both categories.

The push for a union began when Georgetown steelworkers struck in August 1970, at the same time as a satellite wire company in nearby Andrews. Six months into the strike, Local 7898 was born. A May 1971 story on the strike published in USWA periodical Steel Labor hangs under glass by the door.

A lifelong Georgetown resident, Melvin Cohen remembers the picket lines. Still two years from taking a job with the mill himself, he marched with his father.

“They went through some things to get that union here,” Cohen said. “People got locked up, workers got locked up, beat up by the law and different things and I seen it when I was younger what they went through to get the union here. So I take pride in having it here.”

A guard for 7898, Cohen has been with the mill since his hiring in the fall of 1973 as a furnace operator and operations technician. He worked as a truck driver during a previous closure.

After the 2015 closure, Cohen removed slag on the mill grounds until being laid off last February. The union contract allowed him to receive 85 percent of his previous wage for a year, then 65 percent the year after.

“When you look back at that, what the union represents is a whole lot for fairness in mills,” Cohen said.

At 63, Cohen plans to return to the mill when it re-opens to help train new workers. But he still worries about the effect a fourth mill closing would have on his hometown.

“It’s not only going to affect the steel, it’s gonna be a trinkle-down thing,” Cohen said. “When they first shut the mill down we had some people in Georgetown, they said, ‘well, what y’all gonna do when the mill shuts down?’ I said, ‘No, not what are we gonna do, what’s the town gonna do?’”

In December, the S.C. Department of Employment and Workforce estimated Georgetown County’s unemployment rate at 5.7%, just above the state rate of 4.3% and nearly half again the national rate of 3.9%. And in 2016, the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey estimated the city of Georgetown’s poverty rate at a staggering 38.4%.

“For the future, I think if they don’t do something about the imports, that, yeah,” Green said. “It could lead us back to another closure.”

Sanderson believes the tariffs to be a sign of things to come as far as trade policy is concerned.

“This is just the tip of the iceberg,” Sanderson said. “Time will prove that [Trump] was right.”