In January 2019, residents evacuated Allen Benedict Court after two people were found dead from carbon monoxide poisoning. Today, the affordable housing complex has been demolished in preparation for a new affordable development, but residents say they are still struggling. Photos by Christine Bartruff.

Second in an occasional series on housing and homelessness

It’s been nearly three years since Columbia firefighters pounded on Lavice Goodwin’s door in the middle of the night, giving her 15 minutes to grab what she could and evacuate her apartment of eight years.

She still thinks about it every day.

“That was my safe haven,” Goodwin said. “That was my home.”

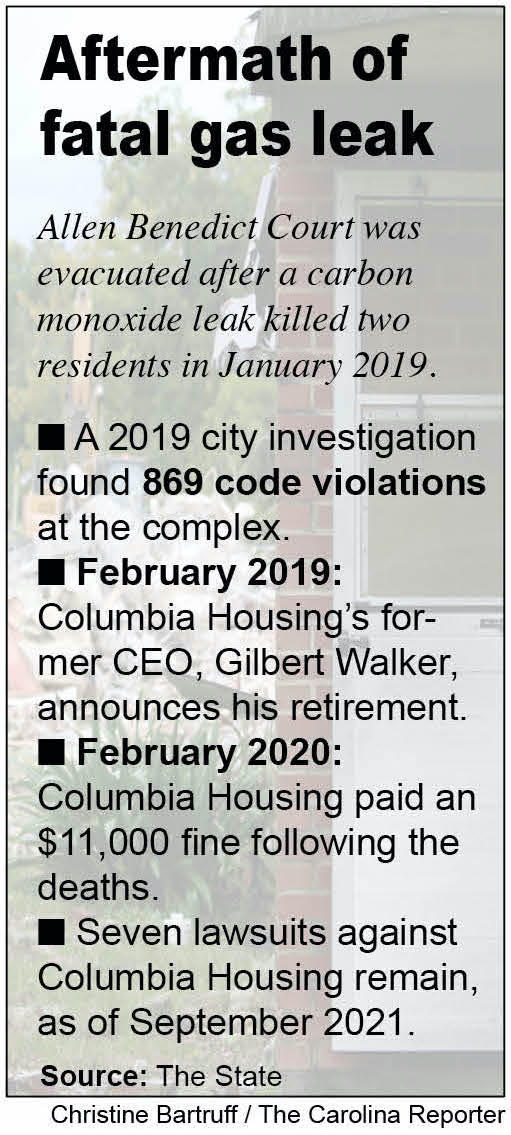

A fatal gas leak displaced Goodwin and more than 400 others from their homes in Allen Benedict Court on a cold night in January 2019 after two residents were found dead, overcome by carbon monoxide poisoning. Trouble had plagued the aging pre-World War II public housing project on Harden Street for years, and residents say their complaints about heating and air conditioning, rodents and bugs were largely ignored.

Now, as the third anniversary of their evacuation looms, former residents say they are still grappling with long-term health problems and communication troubles with Columbia Housing (formerly Columbia Housing Authority). The agency, which is funded primarily through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, manages the Allen Benedict property and provides affordable housing for residents in Columbia, Richland County and Cayce.

“Once they gave us our paperwork to go find us something, that was it,” Goodwin, a parking attendant at the University of South Carolina, said. “That’s how I feel. That’s it. Because they’re not trying to reach out to us, to talk to us about our living arrangement. Do we still want to be here? Can we help you find something else?”

After the evacuation, Columbia Housing shuffled Goodwin among three different hotels before she rented an apartment in a North Main complex. She was starting all over, she said, and while she didn’t love her new apartment, she thought it would provide a temporary roof over her head. She has not been able to find new housing since.

Goodwin has a seasonal full-time job at UofSC’s Bull Street parking garage. She said her rent is $719 a month, about $479 of which she pays out of her own pocket. The other portion of her rent is paid by a Columbia Housing voucher, which helps low-income residents by reducing the portion of rent they pay themselves. The building where Goodwin lives was one of the few that would accept her voucher, she said.

“I just want to go somewhere else besides there,” Goodwin said. “There’s a lot of us from Allen Benedict Court that’s out there, and everybody wanna go, wanna move.”

After multiple attempts to speak with Columbia Housing representatives, Carolina News & Reporter was able to schedule a phone interview with Columbia Housing CEO Ivory Matthews. She did not return the call on Friday.

In a 2020 annual report, Matthews acknowledged the turmoil the evacuation and closure of Allen Benedict had ignited. She wrote, “Six months prior to my arrival, Columbia Housing was challenged with the loss of public trust. Restoring public trust was paramount.” Matthews was named CEO of Columbia Housing in June 2019 after Gilbert Walker retired following the deaths at Allen Benedict.

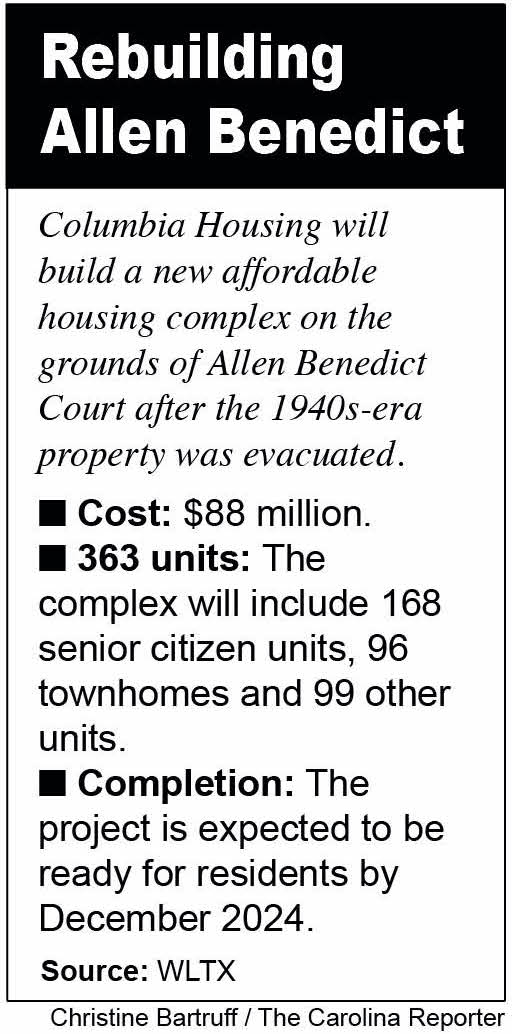

Columbia Housing will spend an estimated $88 million to replace the public housing complex, initially built in 1940 as segregated housing for Black residents in Columbia. The new affordable housing complex will have more than 350 units, which are projected to begin leasing in December 2024, according to WLTX.

Columbia Housing plans to have a total of 2,911 affordable housing units by 2030, an increase of more than 1,200 units, according to its website. The expansion is part of its Vision 2030 plan, announced in May 2021.

But 2030 is a long way off for Tonja Sims, another former Allen Benedict resident. She did not find permanent housing until May of this year. For two years after the evacuation, Sims lived in one-bedroom hotels with her two children, all sharing one bed.

Sims works full time as a housekeeper at a motel. She now lives in a house in Rosewood, where she is dealing with maintenance issues and a broken heater. Like Goodwin, Sims isn’t happy with her current living situation but needed somewhere to stay that wasn’t a hotel.

Safety concerns also weigh on Goodwin, a sentiment shared by her mother and daughter, both of whom are former Allen Benedict residents now living in the same North Main apartment complex.

Gunshots frequently echo outside Goodwin’s window. Two of those bullets struck inside her mom’s apartment.

“If she was there that day, she would’ve been dead,” Goodwin said.

Goodwin has called and sent numerous emails to officials in Columbia Housing about everything from the mildew in her elderly mother’s apartment to questions about moving to another location. She has received inadequate responses, she said.

“Let me start on my own journey,” Goodwin said. “But we ain’t gonna be able to do that if we can’t talk to nobody.”

When Allen Benedict’s replacement opens up for new residents, Goodwin said she isn’t confident she and her neighbors will be at the front of the line. Because of Columbia Housing’s inconsistent communication, Goodwin worries she won’t be kept in the loop on the new development and when it becomes available to rent.

The stress of moving, along with concerns about her safety, has caused health problems for Goodwin. She now takes medication for high blood pressure and depression and battles anxiety and frequent headaches.

“I go straight home and go in my room. I can’t tell you what’s going on in the outside world,” Goodwin said. “That’s where I barricade myself, in my room.”

Trauma implants in the body, according to Columbia-based trauma specialist Jennifer Wolff. Once a traumatic event happens, it is important to seek immediate intervention to prevent severe long-term consequences.

“The world can feel different,” said Wolff, who is certified with the Association of Traumatic Stress Specialists. “The three areas that are impacted the most are trust, safety and predictability.”

Allen Benedict Court was demolished this October. Construction crews cleared out the homes, many of which still contained former residents’ belongings, before tearing down the complex.

“I stood out there that night when they got to my building and tore it down. All our stuff was all out there on the street because you know we couldn’t get nothing out of there,” Goodwin said. “I cried on that one.”

Several residents sued Columbia Housing after their evacuations. Hemphill Pride II, a longtime attorney and civil rights activist, represented two clients who struggled with life after Allen Benedict. They dropped the case due to what Pride described as “intimidation” because they feared speaking out against an agency they rely on for housing.

Seven other lawsuits from former residents are pending in the state court system as of September. Danielle Washington, whose father, Calvin Witherspoon Jr., was one of two residents who died of carbon monoxide poisoning at Allen Benedict, had her case thrown out in federal court earlier this year. Housing’s attorney Charles Turner said Washington’s case did “not rise to a constitutionally significant level,” according to The State.

“Where’s the empathy in that? That was an emergency that was brought on by the housing authority’s negligence,” Pride said. “That was inhumane to me.”

Goodwin has applied to live at other places and hopes to move out on her own. Last year, her doctor wrote a letter to Columbia Housing on her behalf, recommending she be moved elsewhere for the sake of her health. The agency never responded.

“It’s like they done threw us away,” she said.

Lavice Goodwin lived at Allen Benedict Court for eight years before being evacuated. Goodwin, who works at UofSC Parking Services, said she still thinks of her old home every day.

Right before being demolished, apartments in Allen Benedict Court still contained some former residents’ belongings, including toys, furniture and more.

Allen Benedict Court, an affordable housing community off of Harden Street, was demolished in October. Columbia Housing plans to spend $88 million replacing Allen Benedict with a new 363-unit complex.

Columbia attorney Hemphill Pride II represented clients from Allen Benedict who were suing Columbia Housing. The suit has since been dropped, Pride said, but seven other cases remain pending. Photo by Nick Sullivan.

An apartment at Allen Benedict sits in wait of demolition. Goodwin called the apartment complex her home. She felt it was the place she could finally settle down, a dream that shattered after the 2019 evacuation.

ABOUT THE JOURNALISTS

Christine Bartruff

Christine Bartruff is a senior multimedia journalism student from Disputanta, Virginia. She first fell in love with journalism while working on her high school yearbook. Bartruff served as the editor-in-chief of The Daily Gamecock. In summer 2020, she worked at the Stars and Stripes as a Dow Jones News Fund editing intern, where she edited content, reported and worked on a podcast. Bartruff loves telling others’ stories and is interested in reporting on politics.

Nick Sullivan

Nick Sullivan is a senior multimedia journalist and former managing editor of his college paper, The Daily Gamecock. Originally from Cincinnati, Ohio, his favorite part of the job is fostering connections among readers. When the pandemic sent him home, he created his own local newspaper, The Strange Times, in order to bring stories of positivity and perseverance to his community. He has also worked as an editorial intern at Cincinnati CityBeat and a projects intern at The State.