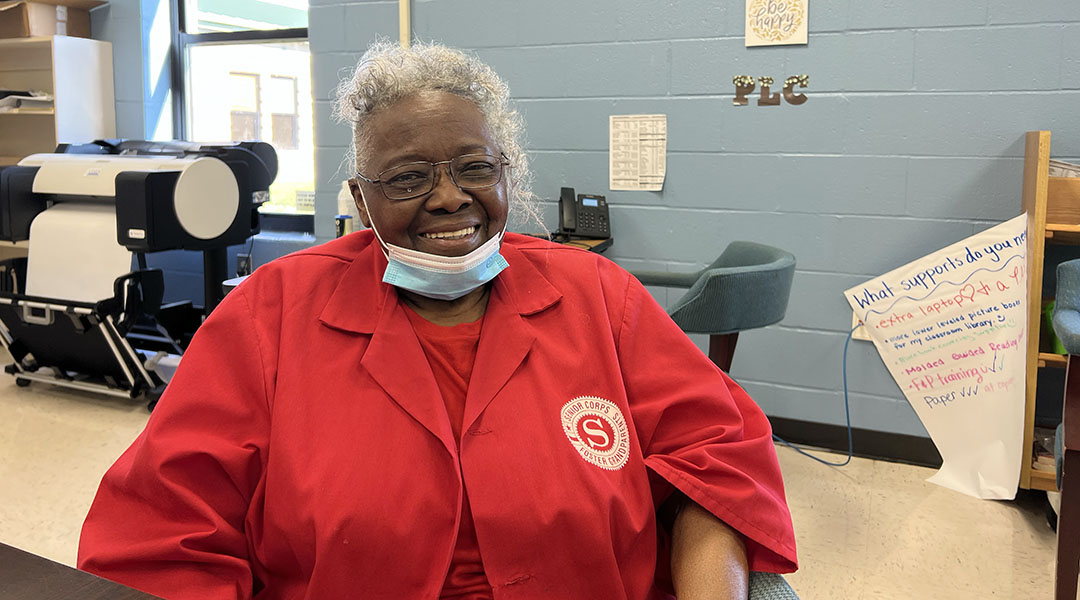

Mattie Bookhart, 89, is a foster grandparent at Forest Heights Elementary. (Photo by Danielle Wallace)

Mattie Bookhart has lost track of the number of kids she has fostered over the years.

She wakes up every weekday morning, eats her Corn Flakes and orange juice, and drives the seven blocks from her house to Forest Heights Elementary School — a routine she has performed for the past 18 years.

Bookhart, 89, has two children, six grandchildren, 12 great-grandchildren — who she calls her “great grands” — and an untold number of foster children. Well, sort of.

Bookhart is one of 71 grandparents who are in the Foster Grandparent Program in the Midlands. The organization, which helps children with learning difficulties, is open to anyone 55 years old, placing them in elementary schools, child development centers and Head Start programs that prepares young children for school.

Program coordinator Larrisa McDowell said the grandparents volunteer between 15 and 40 hours a week. The program is in full swing again as schools lift COVID restrictions.

“We didn’t have a Foster Grandparent Program where I grew up,” said McDowell, who’s from Florence. “But I think it’s a needed program, and it’s really cool, just the intergenerational aspect of it.”

For Bookhart, that intergenerational aspect extends to her blood relatives. Bookhart’s mother was also a foster grandparent, and one of her biological “great grands” is a first grader at Forest Heights she said she occasionally runs into while volunteering.

McDowell said the grandparents are volunteering at elementary schools in Richland One and Richland Two, as well as at programs such as Ezekiel Ministries on Lady Street in downtown Columbia.

Shane Johnson, the program director at Ezekiel Ministries, said his organization has after-school programs that help children year round. He said reading is a major focus, and the foster grandparents have had a large hand in helping the kids improve.

“You act differently, even when an elderly person is sitting in class with you,” Johnson said, “because you look at them as if, ‘Man, this is my grandmother. This could be my grandmother. This is someone’s grandmother.’ So, the respect to our foster grandparents is a world of difference than any of our other volunteers that come in. And I think it’s just because of the natural wisdom.”

Ezekiel Ministries is in its second year working with the grandparents, Johnson said.

“They change the atmosphere, because older people can bring life to the room,” he said. “I think our kids really enjoy working with the foster grandparents. We love them. We don’t want them to go anywhere.”

Bookhart said she spends nearly 30 hours a week volunteering at Forest Heights. Students and staff alike at the school call her “grandma,” unintentionally fostering discussions about race and relationships.

“One (student) come over to me,” she said. “He said, ‘But grandma, she’s not your color.’ I said, ‘It’s not the color – you love everybody.’”

Bookhart said she treats the students at Forest Heights the same way she treats her own — even the one she sees in the school hall only occasionally.

In fact, Bookhart has gone beyond just fostering — she has recruited other senior citizens to help students in need.

“So many children need it,” she said. “Sometimes my heart goes out to some of them because I can’t get to them, and it’s too far away. And they say that, ‘Well, my mom don’t get home (until) 6 and 7 o’clock at night. I need somebody.’”

Monica Geiger is a teacher at Brockman Elementary School, a Montessori school in Forest Acres. Geiger said foster grandparent Patricia Priester has been in her classroom for eight years.

Geiger said she teaches first through third grade, so she has the same group of students for years at a time. This schedule allows the students to spend years with Priester. During COVID, some of Geiger’s students were able only to work with Priester virtually. Priester returned to the classroom mid-September.

“It’s funny because the kids that are now third graders were the ones that were reading virtually with her, so they remember her, but they don’t have that experience with her,” Geiger said. “But they were very excited to see her, because they’ve just kind of like had this bond with her, which is really cool, too.”

And the bond can last a lifetime, even if Bookhart doesn’t always realize it herself. She still runs into students she taught years ago, at places such as restaurants or the mall, who stop to say hello.

“I think I was in the hospital visiting somebody, and this nurse came up to me,” Bookhart said. “She said, ‘Grandma.’ I said, ‘Who are you?’ She said, ‘You don’t remember who I am?’ I said, ‘No, baby, I surely don’t.’ She said, ‘You taught me when I was at Forest Heights.’ … I said, ‘Honey, I’m so sorry, I didn’t recognize you.’ She said, ‘That’s alright. I recognized you.’”

Bookhart said her biological family tells her to spend more time on herself. But the way she focuses on herself is by being a foster grandparent, she said. The program gives her a purpose instead of sitting at home doing her puzzles all day.

“I’m going to be here until I can’t walk, and if they let me come on some crutches, I’ll come,” she said. “They say, ‘You crazy about that job.’ And I said, ‘I’m not crazy about the job. I just want to help the children.’”

Larrisa McDowell, the coordinator of the Foster Grandparent Program at Senior Resources Inc. (Photo by Danielle Wallace)

Forest Heights Elementary School, on Blue Ridge Terrace in Columbia (Photo by Danielle Wallace)

Shane Johnson, the program director at Ezekiel Ministries on Lady Street in downtown Columbia (Photo provided by Shane Johnson)

Picture of Monica Geiger, a teacher at Brockman Elementary School in Forest Acres. Photo taken by Danielle Wallace at Brockman Elementary School.

Ezekiel Ministries on Lady Street in downtown Columbia (Photo by Danielle Wallace)