GameStop has been the focus of both short-sellers and the subreddit WallStreetBets in the last month. Photos by: Matt Tantillo

GameStop’s company slogan is “Power to the Players,” but in mid-January, the company found new players it was never expecting: investors.

On Jan. 12, GameStop’s stock price closed at $19.95, a one-cent or .05% increase from the day before. The stock was cheaper than the cost of buying Minecraft for the Xbox One.

When the closing bell sounded the next day, the price had jumped 57.39% to $31.40 per share. New players had arrived, and they came in the form of a forum on Reddit called WallStreetBets.

WSB saw that hedge funds like Melvin Capital Management “shorted” GameStop, meaning they made a bet that the stock price would go down, rather than up. In order to bet against a stock, hedge funds borrow shares and sell them. They hope to then buy them back at a lower price and return them to the lender, making a profit in the process.

In retaliation, WSB investors decided to do the exact opposite.

Instead of lowering the price of GameStop stocks, WSB banded together to buy as many stocks as they could, raising the price per stock and forcing the short-sellers to pay billions of dollars for their lost “bet.”

It may seem like short-sellers profit off the pain of others, but Chao Jiang, an assistant professor in the finance department at the Darla Moore School of Business, believes people — most notably those in WSB — are forgetting their overall purpose in the market.

“I think there is a general misunderstanding about what short-sellers do,” Jiang said. “What these guys do is they pick the overvalued stocks, short the stocks and push the price down to a fair value. People make money when the price goes down, but most likely, the price was too high.”

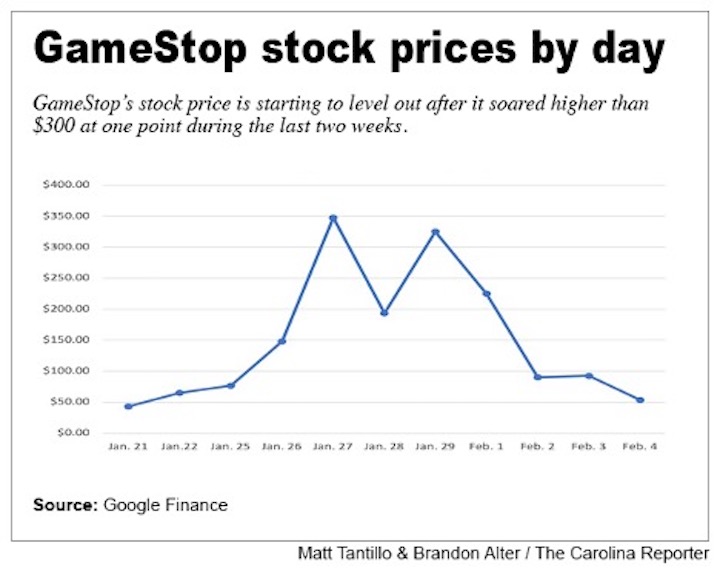

The GameStop stock price continued to soar.

By Jan. 22, the price was $65.01 more than its previous record close of $62.20 on Dec. 28, 2007.

Jereme Hines, 23, quickly began to feel some regret. Although he was a member of WSB, he did not hop aboard what he once considered a “meme train.”

“[I] fully regret it,” he said. “But honestly, for me, it was just about seeing how far they would take it and still taking it. It is fun to watch.”

His fun became Melvin Capital’s worst nightmare. On Jan. 26, the stock had increased fivefold from what it was just two weeks prior as it surpassed the $100 threshold.

It didn’t stop there.

The stock price would hit its high of $483 shortly after 10 a.m. on Jan. 28. Those who got in on the ground floor exited at the penthouse as they capitalized on the record gains.

“I know people who made a lot of money,” said Ian Walters, a first-year business management major. “One of my suitemates’ friends is going to pay off his student loans with GameStop. He made, like, over $100,000. It’s pretty wild.”

The following morning, Robinhood, the platform that some investors use to purchase shares, announced it was going to restrict trading of multiple companies, including GameStop and others in the sights of WSB.

Many felt outraged and betrayed by a company whose supposed goal was to “democratize finance for all.”

“I think that it was kind of catered to be more like anyone can download it on their phone and use it to trade stocks,” said Ben Persohn, a first-year international business major. “Now that they’re limiting it, I don’t agree with that because your whole thing was for the average person.”

Although traders weren’t pleased with this decision, some see where Robinhood was coming from in its decision making.

“I think it [Robinhood limiting the buying of stocks from certain companies affected] was probably a good thing,” Walters said. “It probably needed to slow down. It was something that maybe needed to happen in the market just to give all the big companies a check, but I don’t think it should happen again, personally.”

After a backlash, Robinhood slowly started lifting restrictions. On Feb. 2, long after many angry traders had abandoned the platform, Robinhood allowed traders to buy 100 stocks of GameStop, up from its previous limitation of 20 shares.

By that time, the stock was plummeting. It reached a low of $74.22 around 11 a.m. after Robinhood began to lift its restrictions. It closed at $90.21, a 74.04% decrease from the time of closing just five days prior.

“As a brokerage firm, we have many financial requirements, including U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) net capital obligations and clearinghouse deposits. Some of these requirements fluctuate based on volatility in the markets and can be substantial in the current environment. These requirements exist to protect investors and the markets,” Robinhood said in a blog post.

It wasn’t long after the easing of restrictions that the price rebounded. This prompted conclusions from some that the restrictions were a large reason the stock dropped.

“It is very clear to me that there is a serious discrepancy between who gets to use the stock market one way and [who gets to use it] another way,” Hines said.

The stock price opened at $112.65 on Feb. 3 as traders were able to capitalize on the easing of restrictions and the movement to different platforms.

What’s next remains unknown. In the wake of the market frenzy, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen met Thursday with officials from the SEC and other regulators to discuss market volatility.

What is known is that Melvin Capital lost billions of dollars, with CNBC reporting that it lost 53% in the month of January.

They aren’t the only ones.

Some people who boarded the train long after it left meme station put up hundreds of dollars expecting the stock price to continue to soar, only for the money to vanish within hours.

“The biggest thing for me is, this is a meme,” Hines said. “It might have led to some consequences for Melvin Capital, but that’s only one stock market trader. There are literally thousands of stocks on the New York Stock Exchange. This is literally a drop in the bucket.”

Jereme Hines, 23, regrets not investing in GameStop before it took off.

The stock market attracted savvy new investors as GameStop trended on social media and created volatility.

Following the company’s decision to restrict trading on stocks targeted by WallStreetBets, many have chosen to stop trading with the Robinhood app.