W. Gordon Belser Arboretum was donated to USC in 1959 by alumnus W. Gordon Belser. (Photos by G.E. Hinson)

USC’s W. Gordon Belser Arboretum houses nearly a dozen functionally extinct American chestnut trees.

A deadly blight from Asia was discovered in American chestnut trees in New York at the turn of the 20th century and moved down America’s East Coast.

“At one time there were literally billions of them, and now they’re pretty much all gone,” said Bob Askins, a manager at the arboretum.

The arboretum on the easternmost edge of downtown’s Shandon neighborhood has healthy American chestnut trees from the American Chestnut Foundation. The hybrid trees have blight-resistant qualities.

Doug Gillis, president of the Carolinas Chapter of the foundation, in 2008 helped locate and plant hybrid American chestnut trees at the arboretum.

“The American Chestnut Foundation supplied some trees that were in its breeding program that have some blight resistance,” Gillis said.

Those trees are still standing and have no signs of blight, Gillis said.

The foundation’s hybrid American chestnuts combine Chinese chestnut trees with American chestnut trees. Breeding produces a tree that is physically similar to an American chestnut tree with the Chinese chestnut’s blight-resistant qualities.

“Ours are now getting large enough that they’re producing fruit on their own. So it seems to be an example of a successful experiment,” Askins said.

American chestnut trees that grow in the wild or without hybrid breeding rarely survive into maturity. The blight causes cankers, or areas of dead bark, that spread and cut off the tree’s nutrient flow.

The blight can’t reach the root system. New sprouts grow but quickly die. They can’t mature and reproduce, so they’re classified as functionally extinct.

Groups such as the American Chestnut Foundation and the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry have been researching ways to restore the tree for decades.

The arboretum is a part of the restoration process, although not directly involved in research.

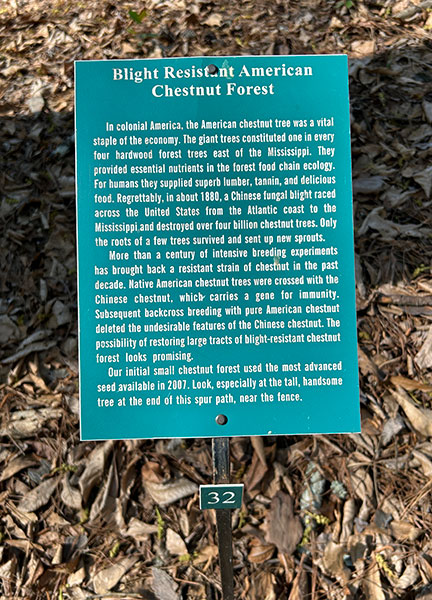

“Demonstration planting is where we’re installing trees, and then we have these signs erected, and then people who come visit will learn about the American chestnut tree,” Gillis said. “… Being able to see one and then also learn more about efforts going on to restore it.”

The arboretum was founded to be a nature preserve and conservation education center. Biology, geology and English classes from the University of South Carolina regularly meet at the arboretum.

Features like QR codes on identifier tags and informational signs allow visitors to both view and learn about the species in the arboretum.

“We have been trying to bring in more plants that fit together in plant communities,” Askins said. “So that presents an opportunity for direct education if you’re talking to groups or indirect just because they can see what those things are and the connections between them.”

Jeff Amberg has lived in the neighborhood since 1997 and shares a fence with the property.

The arboretum’s 10 different biomes allow him and other neighbors to enjoy rare plant life and animal activity in one of Columbia’s largest neighborhoods.

“It’s sort of like part of our backyard,” Amberg said. “It’s a great little wildlife preserve.”

The arboretum hosts open houses 1-4 p.m. on the third Sunday of every month and plans to expand operating hours.