An ancient, sprawling live oak looms over the Colleton County Courthouse, the site of Alex Murdaugh’s double-murder trial. (Photos and graphic by Margaret Walker)

WALTERBORO – Southern hospitality has a new poster child, and it’s South Carolina’s very own Walterboro.

The town is known for its antique shops, historic homes and, as of late, Alex’s Murdaugh’s double-murder trial.

Walterboro is in a lush part of the state that South Carolinians call the Lowcountry.

The air is dense and salty, the coastline is less than an hour’s drive away and the land is full of live oaks delicately decorated with Spanish moss that gently sways in the breeze. Time seems to move slower here.

Walterboro is small. The town has a population of around 5,500, many of whom have lived there for a long time. Folks are friendly. Nobody is a stranger.

The downtown features four restaurants, few stoplights, many antique shops, a post office and the site of the trial: the Colleton County Courthouse, which sits at the town’s main crossroads.

When Walterboro officials were told the town was going to be the location of the double-murder trial, one of their biggest priorities was to be a good host to their guests.

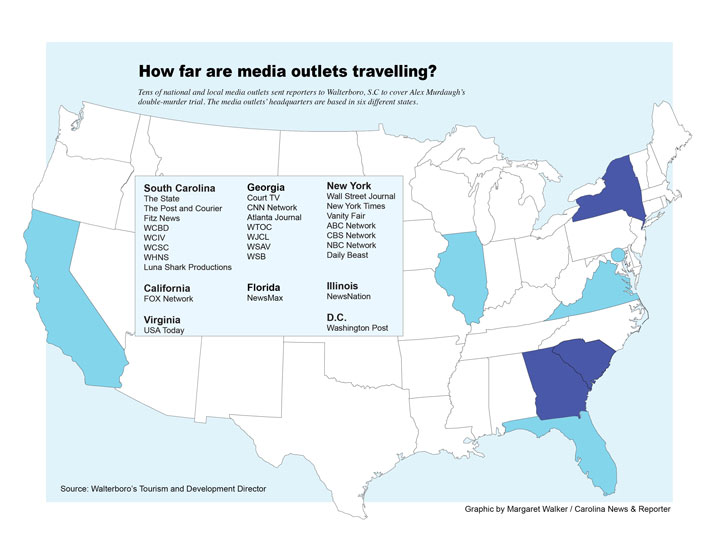

At least 30 media outlets, including the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal and USA Today, covered the trial, bringing in hundreds of staff for the town to accommodate.

“We have an opportunity to make a good impression on people,” Mayor Bill Young said, remembering his initial reaction. “We ought to do everything we can to make that good impression and to make it easy for these people who are here to work, to do their work.”

This desire to make visitors feel welcome and comfortable is common across the South.

But this small town chose to offer Southern hospitality that went above and beyond.

How? With an all-hands-on-deck mentality.

Every detail considered

County and city officials realized their once quiet town was going to be filled with commotion.

It was important to them to help facilitate a seamless trial without shutting down the town, said Scott Grooms, the town’s tourism and development director.

The planning started six months ago. And efforts reached far beyond county and city officials to house, feed and provide parking for the expected influx of people.

“Everything was thought out,” Grooms said.

And for good reason.

Every in-town and nearby hotel was fully booked. Residents rented out their homes through Airbnb and VRBO, and at least one historical society housed media who couldn’t find anywhere else to stay.

The town threw open every door. But why?

“We can’t do anything about the reason that they are coming here, but we can do something about the way they perceive us after they get here,” Young said. “We don’t see this double murder as our murder. The Murdaughs were Hampton people. … We see ourselves as the host for the trial.”

So they got to work. They coordinated with the S.C. Attorney General’s office, as well as the Colleton County clerk of court, the local water and public works departments, police and sheriff’s departments and power and cable companies. Townspeople who voluntarily offered to leave town and rent their homes to those covering the trial also contributed to the spirit of Southern hospitality.

The town set aside parking for the press and satellite trucks to minimize traffic troubles. They turned the new Walterboro Wildlife Center, across from the courthouse, into a media overflow center for the reporters who couldn’t fit in the courtroom. They brought in food trucks from around the state to feed the lunch crowd.

The media overflow center had a projector playing a live feed from the courtroom and was equipped with Wi-Fi, outlets, a generator and tables and chairs exclusively for reporters.

“They have literally done everything in their power to make this comfortable,” said Anne Emerson, a senior investigative reporter for WCIV, Charleston’s ABC affiliate. “You can’t buy this hospitality. It’s seamless from the moment we wake up.”

The town even went as far as planting fresh grass and installing a large flat screen television in the historic 1820 courthouse.

Fair trial, free press

Judge Clifton Newman is highly tolerant of the media, which is lucky, said Jay Bender, a longtime S.C. media attorney.

Newman allowed four cameras in the courtroom. A still camera as well as three video cameras, belonging to CourtTV, shared their work with other outlets via satellite trucks conveniently parked at an old Ford dealership across the street.

For South Carolinians to trust the verdict, the trial had to be public, Bender said. Public trials also are mandated by the state’s constitution.

And, according to Bender, Newman has a unique appreciation for the role of the media.

This isn’t the first time South Carolina has been in the limelight for a high-profile, family-centric, double-murder trial.

In 1995, Susan Smith was tried in Union for the drowning of her two young sons.

“There’s a lot of parallels between the two (trials),” Grooms said. “Small city, limited resources, limited food, limited places to stay.”

Grooms, a Walterboro native, also has a history with high-profile trials.

He had a 35-year career as a TV weatherman, engineer and manager – which is partially why he was asked to step into his current position before the Murdaugh trial.

He worked on the Smith trial and the 2011 trial of Casey Anthony, another parent charged with killing her child.

He said his experience with the Smith trial influenced the way he planned for Murdaugh’s trial.

“I drew on the errors that were made up there,” Grooms said. “If it wasn’t for an IGA (grocery store) and a Hardee’s, we probably would’ve starved to death.”

Walterboro decided to pour money into preparing for this trial, hoping the town would reap the benefits later through positive press and tourism.

“One thing about courts is, there’s not a lot of funding for this,” Grooms said. “They’re like, ‘Hey! You got the trial. You figure it out.’ ”

The goal was to have an organized system where, despite the circumstances, everyone working would have a pleasant experience and not feel as if the town was handling the trial “willy-nilly.”

For the convenience of those who live there, Walterboro closed only one small side street by the courthouse. Everything else remained open.

After the first few weeks, the mayor said the townspeople seemed to warm up to the trial.

“I saw a national media thing the other day, and they didn’t even put South Carolina on there,” Young said. “It just said, ‘Live from Walterboro.’ So I think when they start assuming everybody knows where Walterboro is, that is a pretty big change for a small town, you know.”

Quaint downtown Walterboro features many shops and restaurants.

A projector screen in the media overflow room plays the CourtTV live feed as journalists are hard at work.

Downtown features an antique shop on almost every corner.

This grand and graceful, black and white historic home is located on one of Walterboro’s most prominent streets, Hampton Street.

Religious signs, many reading “Only one way to Heaven … Jesus,” are scattered throughout the town.

Dozens of media outlets travelled to small town Walterboro to cover the Murdaugh trial.