Several questions and phrases commonly appear on assessment tests used to diagnose ADHD. Patients must fill out a questionnaire to see if their symptoms line up with those of ADHD. (Graphics by Kate Robins/Carolina News and Reporter)

Pharmacist Kara McBryde said she was filling prescriptions at Chapin Pharmacy when a high school senior came to the counter.

He asked McBryde if he could have a refill of Adderall, a common medication for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Except there was one problem: He was two weeks early.

Adderall is designed to help people with ADHD focus. But as the United States continues to see a spike in ADHD diagnoses and a shortage of Adderall, experts contend some patients are given too much or sometimes prescribed a drug they don’t need.

“He said he lost it,” McBryde said. “He had no idea what happened to it, so he left because we told him, ‘Either way, it’s a controlled substance. We can’t fill it early.’”

McBryde said the 18-year-old man returned to the pharmacy after calling his doctor, who authorized a new Adderall prescription. A few hours later, the young man’s mom called and informed McBryde he was in the hospital — detoxing from too much Adderall.

“Withdrawal from this drug is pretty awful, so we filled it,” McBryde said. “And I felt really bad knowing that, at the end of the day, that’s 90% of the (time), with people that come in and claim that, ‘Oh, they lost it’ or, ‘It got stolen.’ They’re probably just overtaking it.”

Medical professionals are increasingly questioning guidelines for diagnosing ADHD since the COVID-19 pandemic. Abuse is fueling their doubts.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention is among those sounding the alarm. Rising stimulant prescriptions combined with more ways to get access to healthcare has created more of a need for “clinical practice guidelines for ADHD in adults,” the CDC reported earlier this year.

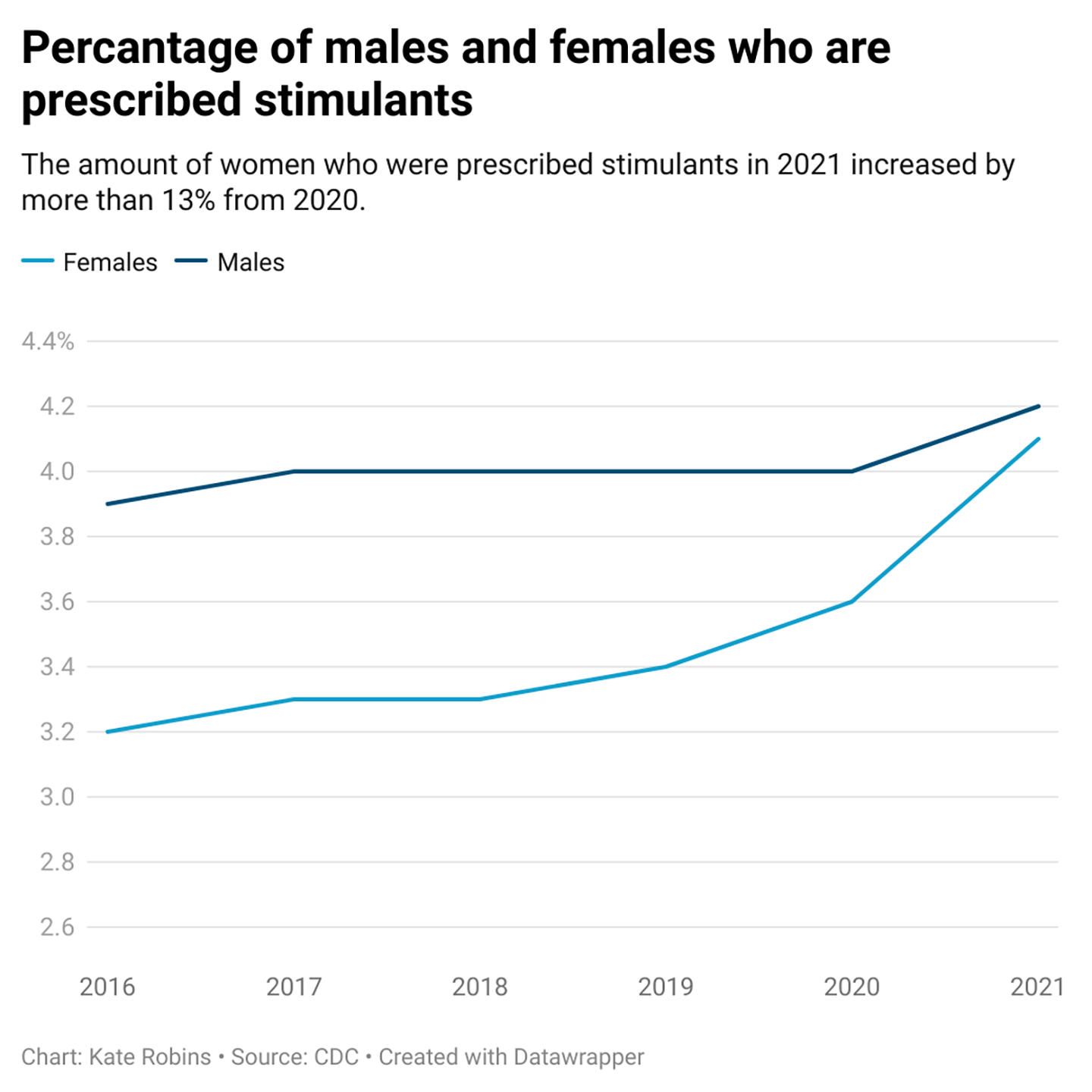

The report also revealed that from 2016 to 2021, the percentage of adults receiving prescription stimulants for ADHD increased substantially.

In 2020, 5.2% of all American women, ages 20-24, had filled a prescription for a stimulant, such as Adderall, according to the CDC’s most recent data. And 6.2% of women in their early-20s got prescription stimulants in 2021.

That means in just a year’s time, the number of women in their early-20s getting prescription stimulants rose more than 19%.

ADHD diagnoses in children have also been on a steady increase since 1997, according to the CDC. Six million children were diagnosed with ADHD from 2016-2019.

Physician: ADHD diagnoses sometimes rushed

Obtaining a diagnosis is often a standard process.

A patient comes in. A medical professional gathers information about symptoms and medical history. Then a test is administered.

The tests vary, depending on age and symptoms. For children, health care providers commonly use the Vanderbilt test — a form with a series of questions, according to Dr. Joe Castles, a Columbia pediatrician at Pediatric Associates.

The 55-question assessment asks children, ages 6 to 12, questions about symptoms.

Castles said the form can give physicians a good idea of whether a child meets baseline criteria for ADHD.

“I can tell if I think this is not just (attention deficit disorder) or this is not just hyperactivity,” Castles said.

He said he also aims to see if the patient is facing issues other than ADHD, sometimes behavioral, that “need to be teased out before we start going down that road.”

From there, Castles said he might examine the child’s home and school life by asking parents and teachers how the patient is sleeping at night, for example, or if they are being disruptive in the classroom.

It’s a multilayered approach. That’s how it should work, Castles said.

But there’s growing concern among medical experts that not all prescribers are as thorough — with pandemic-era data showing a sharp spike in ADHD diagnoses and drug manufacturers struggling to keep up with demand.

Without a full examination, Castles said anything that seems like ADHD could incorrectly be diagnosed as ADHD. Like other health problems, it sometimes could be easier for physicians to have a quick trigger when it comes to prescribing drugs.

“It’s easier to say, ‘You’ve got this bacterial infection’ and write an antibiotic than it is to say, ‘Let me check a few things,’” Castles said. “That’s more time-consuming.”

Columbia-based counselor Isatta Rockman of Sound Mind Counseling Solutions said physicians and therapists often try to gather a full picture of how a child is being affected biologically, socially and physiologically.

Rockman said adults go through a similar diagnosis process. While the questions may be different to fit age and life experiences, the patient still provides a history and takes an assessment test.

Even if a patient shows symptoms and meets test criteria for ADHD, experts say that doesn’t always mean they have the condition.

Medical professionals often perform differential diagnosis, a process that sorts the patient’s symptoms into different mental health categories. Some symptoms for ADHD can mimic other disorders, such as anxiety or depression, Rockman said.

But it sometimes requires a more thorough process to diagnose other disorders, taking more of the physician’s and the patient’s time, Castles said.

Both Castles and Rockman said the increase in mental health diagnoses, particularly ADHD, could partially be attributed to environmental changes during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as to increased awareness on social media regarding symptoms of ADHD.

“There’s more education out there,” Rockman said. “People are more likely to Google than go straight to the doctor. They almost like to have the answer before they go.”

Pharmacist: Prescribing Adderall is easy, getting off is not

The most common way to treat ADHD is through a stimulant, McBryde said.

The medications Adderall, Ritalin and Vyvanse help increase dopamine in the brain, which experts say in turn helps the patient stay more focused.

But McBryde said it’s easy for people to become reliant on the drugs. It takes only three months for the brain to become dependent on the chemicals, she said.

“They cannot get off these drugs, no matter how hard they try,” McBryde said. “And if they try to get off of them, there (are) major emotional changes in them and withdrawal periods. It’s very hard.”

McBryde said about 25% of the overall drugs she dispenses at Chapin Pharmacy are stimulants. On average, she said she fills about 300 prescriptions a day, including 40-50 stimulants.

Both McBryde and fellow pharmacist Chad Hancock said they have seen an increase in adults prescribed ADHD medication.

COVID-19 played a major role in the increase of prescriptions, according to the CDC. While more people were able to access care through telehealth appointments, the CDC reported, the sessions may have introduced “inadequate ADHD evaluations and inappropriate stimulant prescribing.”

“Instead of sitting down in front of a prescriber, maybe going through some psychological tests, these people, potentially, could sit down in front of a clinician via computer screen and walk away the same day with a prescription,” Hancock said.

Adderall prescribed ‘like candy’

Pharmacists can refuse prescription requests in South Carolina, and McBryde sometimes does exactly that.

She said her refusals to prescribe stimulants for ADHD are often tied to certain physicians in the area who are known to prescribe medications “like candy.”

“We see that come in, we refuse to fill it,” McBryde said. “But at the end of the day, they’re probably going to get it sent elsewhere, right? They’re probably going to find somewhere eventually that will fill it.”

McBryde said she sometimes refuses to fill medications from telehealth doctors outside of South Carolina as well.

She said questionable prescriptions are still making their way to patients, particularly from larger pharmacy chains that don’t have as many barriers to keep pills from reaching patients.

But there are other measures in place to try and prevent people from obtaining these controlled substances.

Castles said insurance companies require him to follow up with his patients at least every six months to make sure they still need the medication.

He also makes sure to check during his evaluations whether the child’s family has a history of addiction.

McBryde said she has seen the ADHD medication shortage as a sort of blessing in disguise. That has led to alternative prescriptions, which also have been on backorder.

“If nobody has the drug to fill it for them, they’re not going to be able to get it,” McBryde said. “Eventually, it trickles down, and prescribers will prescribe it last, right? Because they know that nobody can find it anywhere.”

Of the three main drugs, McBryde said Adderall and Ritalin are the most efficient in immediately providing the patient with dopamine. However, they also can be the most addictive.

When the Adderall and Ritalin supplies became more restricted, people were forced to switch to Vyvanse, she said. The drug releases dopamine at a slower rate, preventing the patient from becoming as addicted.

But the biggest drawback to Vyvanse is its price. The drug costs several hundred dollars for every prescription refill compared to Adderall, which can cost around $30, Hancock said.

The Food and Drug Administration approved a wider variety of generic versions of Vyvanse in August. That brought down the cost of the highly demanded medication.

There are more restrictions drug companies could enact to prevent more people from gaining access, McBryde said. Producing fewer pills in a calendar year could help slow the rate of how often patients can take them, she said.

“If somebody wants it bad enough, they’re gonna go out on the street, and they’re gonna go find somebody to buy it from in cash,” McBryde said. “But again, if the manufacturer – if the drug itself – is not there, then it’s not there.”

In terms of diagnosing ADHD, she said some of the processes are outdated and aren’t focused enough on gathering information from experts across fields.

“That’s a lot of time. That’s a lot of money. I get that,” McBryde said. “I know it’s easier said than done. But I think that that’s part of the problem. You throw some drugs at somebody, some of those effects are a little bit harder to reverse.”