Local museums are confident they will be able to keep protesters’ mashed potatoes away from their artworks. (Photos by Caleb Bozard)

A recent trend of climate protesters throwing food and paint onto famous artworks abroad has museum officials on the lookout for similar protests in Columbia.

Climate activists have conducted a string of protests in museums across Europe since the beginning of the summer in which famous artwork has been damaged to raise awareness of climate change.

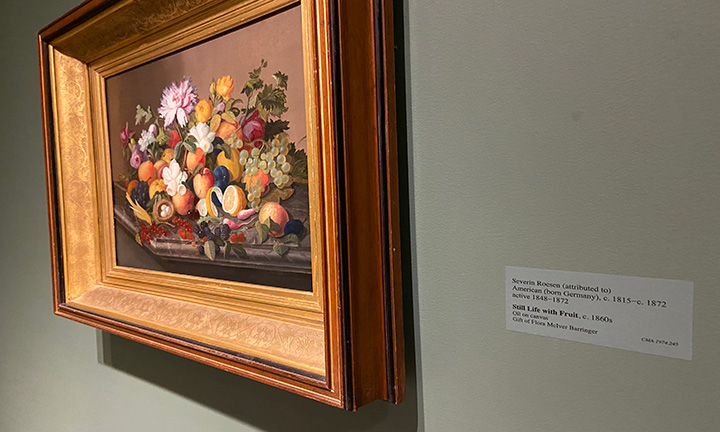

Pieces including da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa,” Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” and Johannes Vermeer’s “Girl With A Pearl Earring” as well as works by Monet and Picasso have been targeted by the protesters. The paintings have had cake, tomato soup, mashed potatoes and glue thrown onto them. Some were protected by glass. But some weren’t.

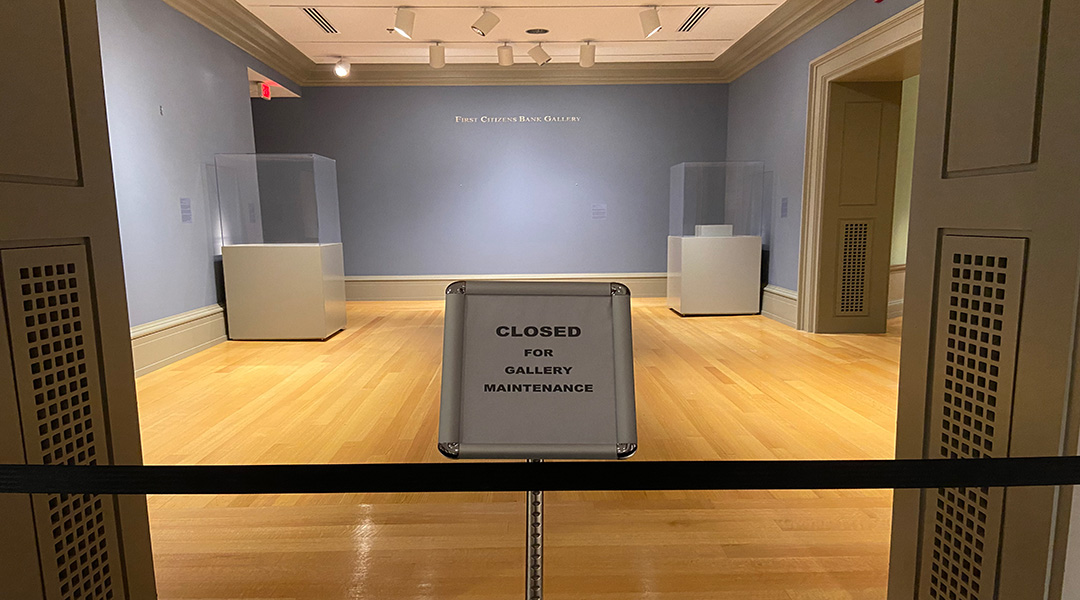

The Columbia Museum of Art and the South Carolina State Museum haven’t seen similar protests, and officials are confident that security precautions will keep their pieces safe from potential damage.

The State Museum has standing security protocols that include “internal databases and regular inventories, onsite video cameras, security staff and gallery monitors in exhibition spaces, trained art handlers and secure display mounts” for pieces on display and in storage, museum public relations manager David Dickson said in an email to The Carolina News and Reporter.

The Columbia Museum of Art is keeping an eye on recent events, Jackie Adams, the museum’s director of art and learning said in an email to the News and Reporter.

The museum doesn’t discuss specific security measures as a general policy, Adams said. But the museum does have “protocols and guidelines in place that are regularly assessed and practiced” to prevent acts of vandalism. Food, drink and open containers are not allowed in the galleries. Security guards regularly patrol the exhibition spaces.

“All in all, while these incidents spike curiosity and headlines, we keep a consistent protocol in place for these and any myriad of incidents that may occur,” she said.

While some of the art museum’s pieces on display are behind glass, others are not. In the protest targeting the “Mona Lisa” in Paris, the protective casing surrounding the painting prevented the food smeared onto the case’s surface from touching the piece.

Most of the pieces targeted have reportedly not been seriously damaged, even those that aren’t surrounded by protective casing.

If something does go wrong, outside conservators are contracted to do any restoration, repair or conservation on any artwork at the State Museum, Dickson said.

The amount of restoration work required for the paintings would depend on many factors, including the substance thrown onto them, said Ivan Kershner of The Painting Doctor in the Upstate’s Oconee County.

“If you throw ketchup, let’s say, on a painting to make it look like blood, (that’s) pretty easy to clean off,” he said. “But if you throw on super glue, which is a polymer, onto an oil painting, you know — big problems. So it depends on not only the work of art, but the type of stuff you’re damaging it with.”

Repairing damage to the canvas of a painting is one thing, but replacing the content painted onto that canvas is another, he said.

The Oil Doctor is a mom-and-pop artwork restoration service run by Kershner and his wife. They usually work on pieces from local, private collections, but they have done work for Clemson University and have restored paintings from as early as the 1600s, he said. Kershner said his wife recently restored a Monet.

“The processes are going to be basically the same whether you’re restoring a Monet or a painting by your great-grandmother,” he said. “A hole in the roof of the White House or a hole in the roof of Bill’s house down the street from where you live basically require the same procedures.”