The auditoriums at AMC Harbison 14 in Columbia are currently operating at 40% capacity and patrons are required to wear masks unless they are eating or drinking. Photos by: Taylor Washington

Quinn Kinsler left AMC Harbison 14 with three kids in tow, still giddy with excitement at what they just watched. How exactly are middle schoolers supposed to act after seeing a giant radioactive lizard and a 300-foot-tall gorilla battle it out on the big screen?

She admits she would have preferred to watch the movie from home but didn’t mind relenting for one night. This was the Kinslers’ first time taking a trip to the movie theater since the coronavirus pandemic shuttered theaters for approximately five months last year.

“I can’t necessarily say that I felt completely comfortable, but it’s spring break, and the kids have to do something,” the Columbia resident said.

“Godzilla vs. Kong” is officially the first pandemic box office hit. During its opening weekend, the film boasted the biggest box office debut compared to every other film released during the pandemic, according to Variety. Additionally, millions of others opted to stream the film from their homes on HBO Max.

When Warner Bros. announced it was releasing its 2021 slate exclusively on HBO Max last December, the reaction was split. Half of the internet was grateful for the opportunity to still watch new films and the other half was concerned about the precedent this would set for future releases.

Lauren Steimer fell into both camps. As an avid moviegoer, she was ecstatic, but as a film professor, she knew what this would mean for the future of theaters.

According to Steimer, a Chinese company called Delian Wanda became a majority stakeholder in AMC Theatres before the pandemic with hopes to revolutionize the industry. However, the company gave up its majority shareholder status in March, showing just how much the pandemic has rattled an already vulnerable industry.

“It’s an industry that has struggled for a long time, but they thought it would work. And they thought that they could find a way to make a profit off of it. And the pandemic has kind of exacerbated their exit from the industry,” the University of South Carolina associate film and media studies professor said.

In the past decade, Chinese investments in theater companies were seen as a solution to help curb steadily declining attendance rates, Steimer said. Now, the biggest battle in the industry has shifted to streaming and how to capitalize on its popularity since these investments have turned into divestments.

“Even before the pandemic, the studios were fighting with the exhibitors on how soon they could release things to streaming after it had been in theaters, so the pandemic really helped the studios gain more leverage over that.”

Although she believes the theater experience won’t go away entirely, Steimer predicts that the number of theaters will shrink. Eventually, they may be owned by major studios because of the leverage they have gained over smaller distributors during the pandemic.

The nonprofit Nickelodeon Theatre on Main Street is one of thousands of arthouse theaters fighting to stay alive – and with significantly fewer resources than bigger names like AMC.

Thaddeus Jones, the director of programming at the Nick, said the theater expanded the options it provided to patrons. The theater currently has virtual screening rooms that allow patrons to watch new films from their computers. Still, it’s been tough to earn revenue when the theater’s doors have been closed for over a year.

“When you have people come in-house, there’s other opportunities to increase ticket prices,” Jones said. “You buy your ticket, but then you buy popcorn, or you buy candy, you know what I mean. So those different things don’t exist at this moment and so it’s been a struggle for the Nick to continue to drive revenue.”

Compared to AMC, the Nick is limited to what kinds of films it screens because it isn’t affiliated with any major studios. Not only are those films not for their audience, but they’re also expensive to screen and investors would expect a return that the two-screen theater would not be able to provide.

Because of this, many arthouse theaters have struggled significantly more than bigger-name theater chains. Still, Jones is sure arthouse theaters will always have an audience and believes the pandemic has just provided viewers with new options in how they watch movies.

“I think what you’re going to find is that, in the coming future, you’re going to see more big-budget films in theaters, medium-range films are going to get those streaming releases, and then you’re going to find some art house theaters doing smaller independent films that are going to have trouble getting onto a platform,” Jones said.

While he would love to see droves of people in theater seats soon, Jones said he understands why the convenience of streaming appeals to the general public.

Amanda Manea from Bellevue, Washington converted to streaming during last year’s lockdown period and doesn’t plan on going to the movies anytime soon because she has everything she needs at home. Last year, she subscribed to HBO Max, Disney + and Showtime.

“A lot of these platforms also came in packages, like there weren’t packages available before the pandemic. And I definitely have been streaming more and honestly, I don’t know if I would be as likely to go to the movies anymore,” she said.

On the other hand, Graham Shroyer has been to the movies a handful of times since theaters opened up and is eager to return.

The Columbia native was an avid moviegoer before the pandemic, going as often as twice a week. While he believes streaming has its perks, he said nothing compares to seeing movies the way they were meant to be seen.

“There are some big movie moments that need to happen in the movies. You know, when I first watched “Avengers: Endgame” in the theater, and everybody’s like, experiencing it together on the big screen, that’s why people always say like, ‘Oh, movies meant to be experienced in the theater,’” Shroyer said.

This is why the trend of releasing blockbusters immediately to streaming platforms has him worried studios will lower the quality of their films.

“What’s the purpose of making “Godzilla vs. Kong” so big and loud and expensive if you could basically have the same experience on television?” he said.

Even so, he knows that it will be hard for theaters to compete with streaming services when a monthly subscription is about the same price as a single movie ticket and he understands why these shifts in the industry are happening.

The popularity of streaming has steadily increased since its inception and it has killed the video rental service, encouraged cord-cutting and currently threatens the future of movie theaters. Only time will tell if the changes the industry is making will be enough to save it.

But like Shroyer, Jones is adamant that the theater experience is irreplaceable because even more than spectacle, the theater experience gives people the community they crave.

“When I’m in a theater, I’ve been here, and now I can’t wait to talk about what we shared, and what we saw, and what I thought, and what you thought, and how this movie has affected us moving forward. So that shared experience is a completely different field than sitting at home,” Jones said.

“Godzilla vs. Kong” currently boasts the best box office debut for a film released during the pandemic. Over 3 million people have streamed at least 5 minutes of the film on HBO Max, according to Samba TV.

The Nickelodeon Theatre on Main Street is still closed in person but has virtual screening rooms that allow patrons to watch new films online.

Film and media studies professor Lauren Steimer said movie theaters generate profits from selling food and drinks, not tickets.

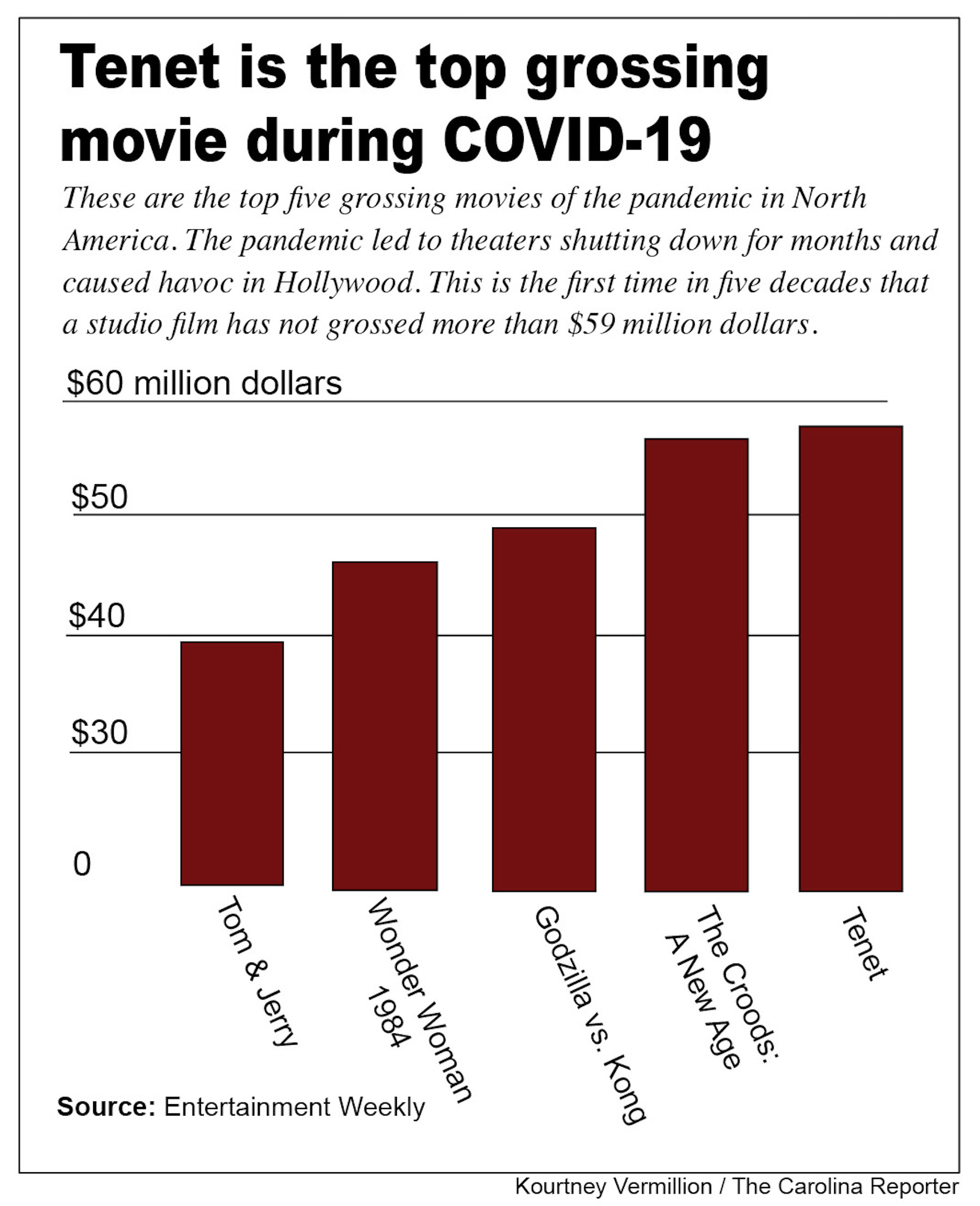

Graphic by: Kourtney Vermillion