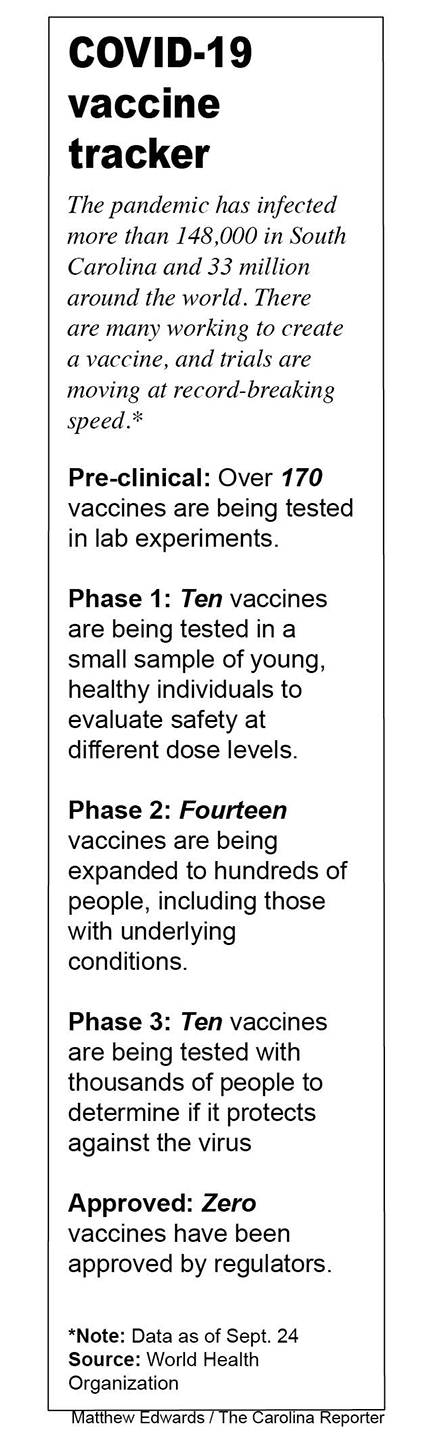

South Carolinians and others across the U.S. are participating in trials to study the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines.

When “Tom,” a middle-aged South Carolina healthcare professional, calculated his odds of contracting COVID-19, he decided he might improve his outlook by participating in a vaccine trial.

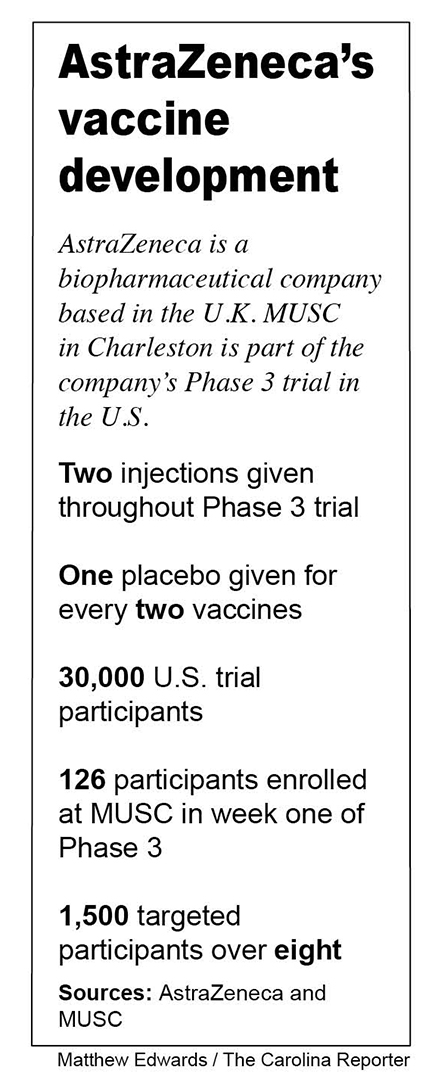

He was one of 1,500 individuals accepted into a trial at the Medical University of South Carolina conducted by AstraZeneca, a United Kingdom-based global biopharmaceutical company. The company began its Phase 3 clinical trial in the U.S. for its AZD1222 vaccine earlier this month, which meant Tom, like 1,500 others in the MUSC trial, received a vaccine or placebo.

AstraZeneca is among several companies that are engaged in Operation Warp Speed, a coalition of federal agencies and private firms created by the U.S. federal government to deliver 300 million doses of a COVID-19 vaccine by January 2021.

“I would be lucky to not get COVID-19 before next year,” the healthcare professional, who requested his identity be masked by a pseudonym because of the nature of the trial, said. “I view it as a quick way to get a COVID-19 vaccine that may protect me, and I think it’s reasonable to help scientific information.”

As the coronavirus continues to ravage the United States and countries across the globe, Tom is one of thousands who are participating in trials that raise hope for a return to a normal life.

The day of the first injection

Tom went to the clinical testing site for his first injection in early September. He answered questions about his medical history on an iPad, signed several consent forms and completed a physical exam and COVID-19 test with a nurse practitioner.

Tom received his first dose of the vaccine that same day. He went home thinking he received the placebo because he felt normal. A day later, he started having mild symptoms.

“The next morning, I felt chills and checked my temperature, which was low,” Tom said. “About an hour later, I felt warm and sudden fatigue. My temperature was 100, and it stayed there until the next morning.”

Tom said he did not change his daily activities, but he tired more quickly than he normally would. A few days later, he started having discomfort in his arm where the vaccine was given.

Tom downloaded an app called Study Hub to log his symptoms and answer a questionnaire for seven days. Follow-up phone calls were received on the seventh day after the injection.

Tom thinks he might have received the vaccine instead of the placebo, but he is not certain. He is looking forward to his next steps in the trial, and he is scheduled to receive the second dose in early October.

The AstraZeneca vaccine was invented by the University of Oxford and its spin-out company, Vaccitech. According to AstraZeneca, the vaccine uses a replication-deficient chimpanzee viral vector based on a weakened version of a common cold virus found in chimpanzees that contains the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

After an injection, the spike protein is produced, preparing the immune system to attack COVID-19 if the virus later enters the body.

AstraZeneca’s trials were paused on Sept. 6 to investigate the case of a participant who became ill. The company resumed clinical trials in the U.K. following confirmation by the Medicines Health Regulatory Authority, but it has yet to receive approval from the Food and Drug Administration to resume trials in the U.S.

On Aug. 19, the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston was one location selected to test the AstraZeneca vaccine in up to 1,500 people as part of a national effort to study the vaccine’s effectiveness. Around 30,000 people are involved in AstraZeneca’s two-year trials in the U.S.

Charleston was selected because of its high infection rate, with the county accounting for more than 15,000 cases since early March.

Tom knew he had a good chance of receiving the potential vaccine, based on AstraZeneca’s trial method. Trial participants are randomized to receive two doses of AZD1222 or a placebo four weeks apart, with twice as many participants receiving the potential vaccine than the placebo.

A different drug company, but the same end goal

On the west coast, San Diego, California, residents Adam, Robert and Clay are enrolled in the Moderna vaccine trial. Their last names are also omitted because of confidentiality.

Moderna’s potential vaccine, mRNA-1273, was developed by the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based biotechnology company and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Moderna was the first trial to be implemented under Operation Warp Speed.

Like Tom’s trial with AstraZeneca, Phase 3 of the Moderna trial involves testing a vaccine or placebo in humans. Adam, Robert and Clay’s first appointments at the testing site were similar to Tom’s in South Carolina. They each had to sign consent forms, take a COVID-19 test and complete a physical exam.

Adam chose to enroll in the San Diego trial because he is a nurse and at high risk for catching the virus.

“We get COVID-19 patients every day at the hospital, so I thought I have nothing to lose,” Adam said. “I also wanted to help out science and be a part of a solution.”

Adam said he had soreness for a few minutes in consecutive days after his first injection on July 31. His second injection was on Aug. 27, and he felt chills for 30 minutes once after a nap.

“I was wondering if it was a ‘mind-playing-games’ type thing,” Adam said. “My roommate is in the trial and had a bad fever for a whole day. I’m assuming I probably did not get the vaccine since none of my symptoms were lasting.”

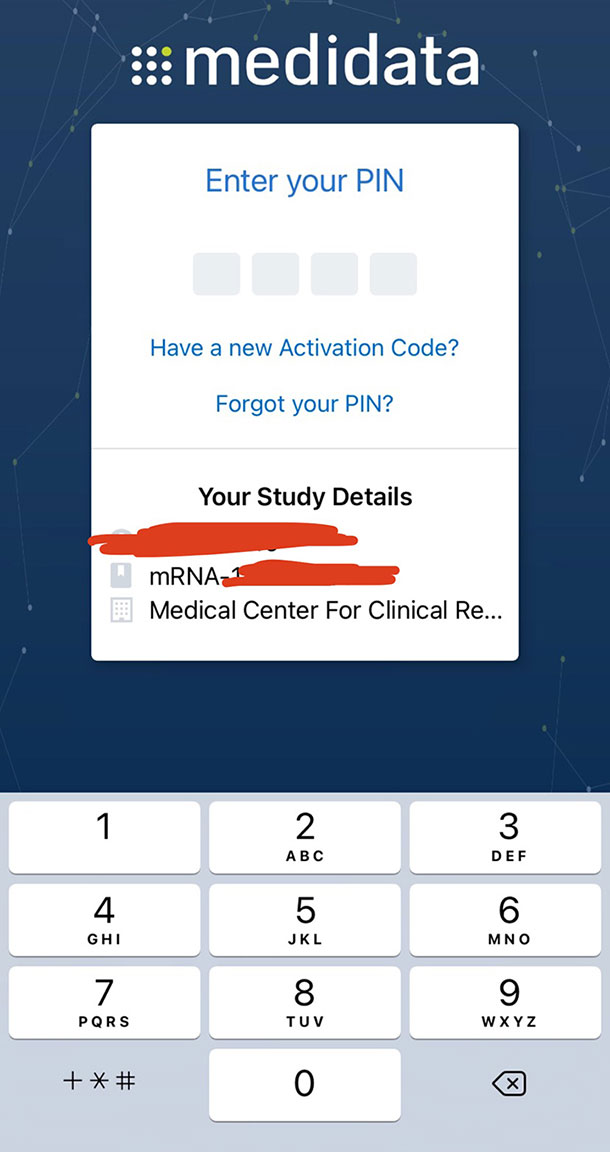

Adam did not report his short-lived symptoms to the Medidata Patient Cloud app, which he used for one week after each injection.

Clay, an environmental biologist, believes, like Adam, that he received the placebo because he had no symptoms.

Robert, on the other hand, believes he received the vaccine. Like Tom, his second injection produced more symptoms than the first.

“With the first one, I had a sore arm,” Robert said. “With the second dose, I had the sore arm, fever, headaches, fatigue and body aches. Several people I referred to the study had the same side effects.”

After his second injection, Adam said the remainder of the trial is a waiting game. He will have a couple of appointments to get blood drawn.

“If you test positive for COVID-19, they follow you, and you will have a couple of in-person and virtual appointments,” Adam said. “So if you get sick, it expands a little more.”

Adam, Robert and Clay were told that if the vaccine is released before the end of Moderna’s two-year study, the company will open each participant’s records and let them know if they received the vaccine or the placebo.

“If we received the placebo during the trial, they would give us the vaccine at that time,” Clay said.

While it is unknown exactly what month an approved vaccine will be released, scientists and vaccine makers like Moderna and AstraZeneca have long said several vaccines could be available by the end of the year.

According to recent polls in the U.S., only half of Americans would get a vaccine if it were available. Some Americans have also spread conspiracy theories contributing to anti-vaccine movements.

Tom, Adam, Robert and Clay said it is unfortunate misinformation campaigns like these occur. They wish more people had faith in fact-based science.

“I realized back in February there’s only so much I can do on an individual level,” Tom said. “I could see that the level of misinformation was going to blow away anything that a doctor could tell 10 or 20 patients in a day.”

According to experts, if everything goes as planned, people in high-risk groups could receive the approved vaccine this year. Others will have to wait until anywhere from a couple to several months into 2021.

“This vaccine is built off of the information gathered from the SARS outbreak in 2003,” Tom said. “This is all beneficial for the next pandemic, whenever that may be.”

Adam, a San Diego resident in the Moderna vaccine trial, uses the Medidata Patient Cloud App to log symptoms. Symptoms must be logged for up to seven days after each injection. Photo: Adam

AstraZeneca’s vaccine was invented by the University of Oxford in the U.K. and its spin-out company, Vaccitech. The trial was temporarily paused Sept. 6 over potential safety issues when a participant fell ill.