Women in South Carolina aren’t going back to routine doctor’s appointments after the pandemic, according to health experts. (Photo by Leah DeFreitas)

After not attending preventative healthcare appointments in 2020, Anne Claire Purcell found lumps in her breasts during a self-exam in the spring of 2021. Purcell scheduled biopsies and ultrasounds, and she navigated those appointments with women’s health specialists throughout the pandemic.

By the time doctors removed the fibroadenomas, the 21-year-old’s tumors had doubled in size in just six months.

“If they are malignant, the consequences are breast cancer, which is terrifying for such a young age,” Purcell said. “Otherwise, they would have just kept growing. They’re uncomfortable. They hurt.”

Doctors found Purcell’s tumors were benign, or not cancerous, and removed them this summer.

Purcell and other South Carolina women have delayed health screenings since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing women’s risk of discovering issues in later stages and at greater severity.

Public health experts say COVID-19 will continue to have a lasting impact on women. New research is beginning to show the extent of that impact — South Carolina has yet to see women attending healthcare appointments at pre-pandemic levels.

So, really, why are women not going back to the doctor?

The Carolina News & Reporter spoke with 23 women ages 18-25 in Columbia, most of them students. Almost half said they had delayed, postponed or avoided a women’s healthcare visit. Of those 11 women, 9 attributed the delay to COVID-driven anxiety or emotional reasons.

Purcell was one of those nine women. She said the transition to college coupled with the pandemic increased her anxiety around arranging primary care. That made it difficult to create positive relationships with local doctors.

“I just got a dentist up here,” Purcell said. “I hadn’t been to the dentist in three years.”

Young women should get their first Pap smear at age 21 to screen for cervical cancer or other issues, according to the Mayo Clinic. Purcell is one of many college-aged women whose first preventative pelvic exam or Pap smear should have taken place during the pandemic.

Kayla Freely, a 21-year-old USC student, said she has yet to get her first Pap smear.

“It was harder to get a full medical exam when everything was telehealth,” Freely said. “Everything was put on hold.”

Delaying her healthcare became a habit, Freely said.

“Now I’m just used to not going at all, not taking care of myself,” she said. “I wish it were more spoken about at school.”

Nationally, after a sharp decline in breast cancer screenings in 2020, the frequency of exams has returned to only 85% of pre-pandemic levels, according to a study by the Journal of the American College of Radiology.

“With breast cancer, early detection is key, and many women fell through the cracks,” said Jennifer Sobich of the National Breast Cancer Foundation.

Staffing shortages, facility closures and fear of COVID-19 caused the initial drops in all non-emergency procedures. Today, organizations such as the American Cancer Society are researching ways to close the remaining cancer-screening gaps.

Less screening means fewer cases are found – for now. And additional cases are likely to show up later.

Those screening gaps also mean an increase in health disparities for women who already experience inequity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In South Carolina, screening gaps hit rural areas harder.

Edena Guimaraes, a professor at the University of South Carolina’s Arnold School of Public Health, said COVID-19 created larger screening gaps for women in rural areas than in metropolitan areas. South Carolina is 29% rural, according to the S.C. Rural Health Report.

“We know that some women didn’t go because they felt like it was difficult to go to the doctor if they weren’t vaccinated,” Guimaraes said. “Women in rural areas weren’t vaccinated, so they weren’t going to the doctor.”

Insurance was another pandemic issue.

Fifteen percent of women in South Carolina didn’t have health insurance during the pandemic. That was the third-largest percentage in the United States, according to a study by Value Penguin.

“Women are less likely to have health insurance, less access to healthcare, so they’re less likely to go,” Guimaraes said.

That doesn’t even include the fact that women aren’t listened to by doctors as much as men, which also likely increased the delays, Guimaraes said.

“Women (for) years have learned if you go to the doctor, they never believe you,” Guimaraes said. “They blame your pain on anxiety or hormones. Women say, ‘Why would I want to put myself through that crap?’”

Guimaraes urges any woman postponing an appointment to act.

“Women, as nurturers, tend to put the health of others above their own,” Guimaraes said. “But if you’re not healthy, you can’t be a nurturer. Without health, what do you have?”

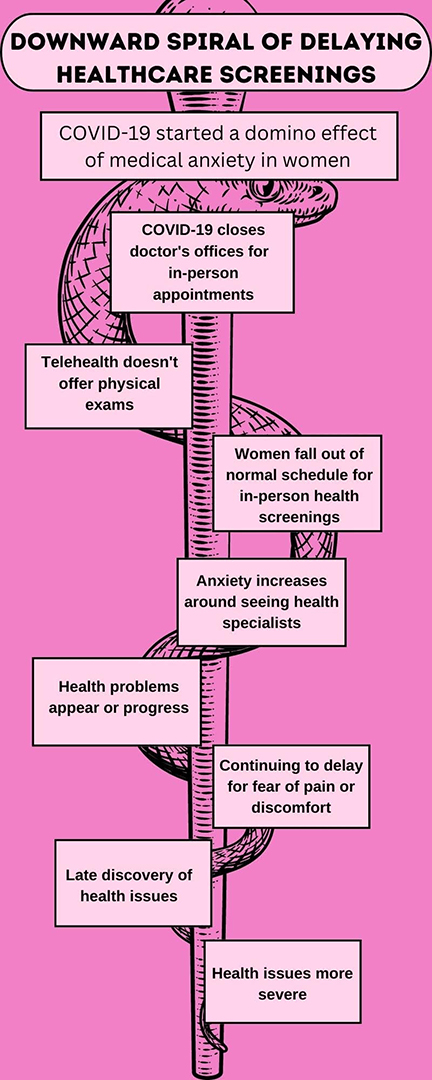

The pandemic set off a pattern of delayed preventative health screenings, especially for women. (Infographic by Leah DeFreitas, Holly Poag and Noah Watson)