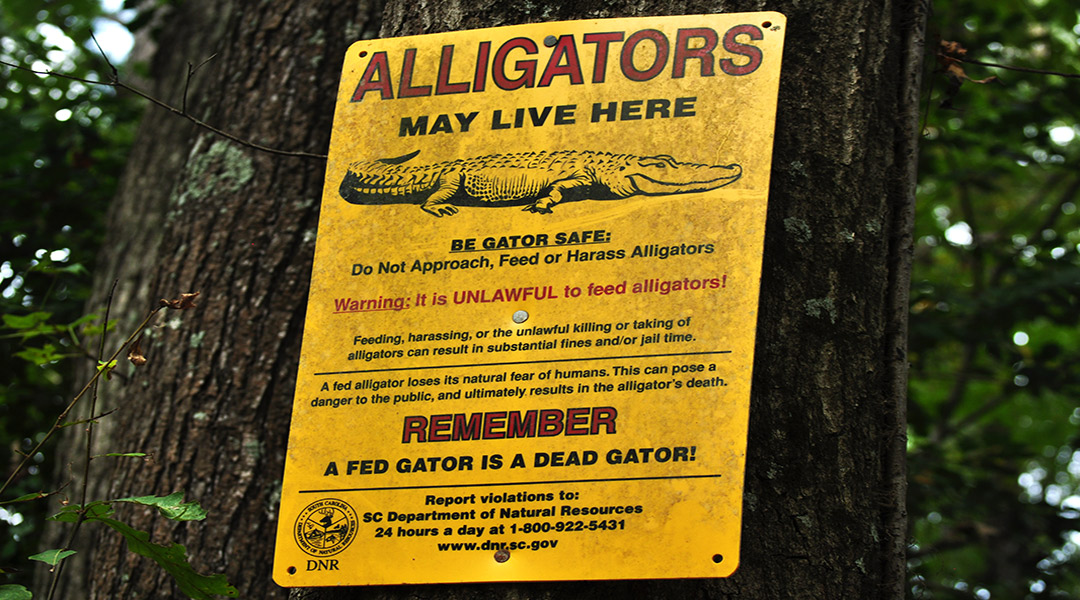

A sign warns passerby’s to “be gator safe” and stay aware along the Timmerman Trail in Cayce. The park closed briefly in 2017 after a sighting of a 9-foot long alligator. Photos by Destiny Stewart

A recent viral video captured in Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, exposed an alligator’s cannibalistic palate and created misconceptions about the reptile’s eating habits that wildlife experts are working hard to dispel.

The alligator species is widely known to feed on dead carcasses called carrion. The prey in the video was a smaller alligator that had already drowned shortly before, according to Taylor Soper, who originally posted the video on Twitter.

Soper says his father was enjoying a day on his porch when he witnessed the 12-foot-long alligator devour a smaller gator.

“(He) was kind of amazed that it happened,” said Soper. “(The fact that) he even had a chance to capture it on camera and just be able to see all that…that’s not at all a very common occurrence.”

The nervous system of an alligator is similar to that of a chicken, and the carcass will continue to flail for moments after death. This phenomenon has made shocking video seem a lot worse than it is.

Morgan Hart, an alligator program biologist with the S.C. Department of Natural Resources, said the alligators are “not monsters, just wild animals.”

Soper says that his family members are no strangers to wildlife. Just days before the incident, they witnessed a baby gator get eaten by the same six-foot-long alligator that was prey in the video.

Joshua Castleberry, the environmental and natural resources chair of Central Carolina Technical College, said though he understands the initial shock factor of the video, this is fairly common in nature.

However, catching an interaction like this on camera is still rare because larger alligators of this size aren’t as common anymore.

“It happens all the time with baby alligators,” said Castleberry. “They’ll call out in distress and the mothers will respond. Unfortunately for the baby, the noise attracts larger males who would happily snack on easy prey.”

“It is just the circle of life,” Hart said.

Soper and his parents are hesitant to disclose the exact location and details of where the alligator incident occurred.

“We just don’t want the alligator to be bothered… that’s nature,” said Soper. “It wasn’t like he was attacking a human or anything like that. He was just kind of doing his thing, and it just happened to be in the pond behind the house.”

Hart says the DNR estimates there to be around 100,000 alligators in the state. Though the population is currently stable, the American Alligator was formerly listed as endangered.

Alligators are known to “self manage” their population, according to Hart. The alligator will fight its own kind over “property disputes” and other threats to its habitat.

They are legal to hunt, though it is tightly managed. They are predominantly hunted for sport because there is generally very little investment return on alligator hunting: Alligators are more expensive to hunt than they are to process and sell. This year, the “lottery hunt” runs from Sept. 11 to Oct. 9.

Wild alligators that present a threat to pets, livestock or humans are considered nuisance alligators. In case of emergency or requested removal of a nuisance alligator, the DNR has a list of resources. There are also local wildlife extraction services that specialize in alligator removal.

“They will stay to themselves, but they will definitely defend themselves when provoked,” said Hart.

The DNR reported its most recent alligator attack Monday morning. A Hilton Head man in his 70’s was doing yard work near the edge of a pond on a golf course when he was attacked. A nearby golfer came to help the man, who suffered serious bites to his arms and legs, according to the report.

“When they do attack, it is generally because people either displayed weakness, short circuited their predatory behaviors by feeding them, or took a risk like swimming at dawn or dusk,” said Castleberry.

Castleberry said alligators are generally wary predators, hardwired to choose weak or easy prey to reduce the risk of injury to themselves and increase spent energy.

There is a common misconception that alligator attacks can be avoided by running in a zigzag line. Though it is true that they do not turn well or run quickly for far lengths at a time, this is not the best method of prevention.

In case of an alligator attack, Hart says there are two important rules.

First, it is important to always assume that any waterway below the fall line, a South Carolina geographical region, will be inhabited by alligators. Always be aware of your surroundings, especially near water.

Do not feed the gators. Hart and Castleberry both describe the species as afraid of people, but a fed gator will “begin to lose its natural fear of humans,” said Hart.

“If you want to keep your fingers, do not approach.”

There have not been any recent sightings of alligators in Columbia. Castleberry said the closest he has seen was in the Congaree National Park.

“It is not likely,” said Castleberry. “Though as a naturalist I have learned to never say never.”

Timmerman Trail is a part of more than 83,000 acres of protected land and water across the state. Before 2013, the American Alligator also found itself amongst DNR protection as an endangered species.

Morgan Hart works with the DNR to illuminate the lives of alligators, a toothy reptile that typically inhabits swamps, marshes, and freshwater lakes. Photo courtesy of Morgan Hart

The wild vegetation lining the water’s edge makes for easy camouflage for alligators and other wildlife.

Call boxes like this one on the Columbia Riverwalk can be used to quickly alert medical services in case of an alligator attack. Photo by Meghan Hurley