Billy McCord, who received his undergraduate and master’s degrees in wildlife and fisheries biology at Clemson University, spends almost every day along the South Carolina coast researching, catching and tagging monarch butterflies. Photos by: Rachel Strieber

On a recent week day, Billy McCord crashed through a tangle of bushes in Folly Beach in pursuit of the monarch butterfly, the fragile orange-striped beauty that has occupied his scientific mind for decades.

He’s the state’s most active monarch chaser.

“I’m not smart. I’m just weird. Monarchs have my life.”

McCord chases butterflies almost every day on James Island – an ideal spot for catching migratory monarchs near the ocean. McCord retired from the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources in 2010 as an ecologist and naturalist, but still comes into the office each day as an unpaid part-time employee, researching and tagging monarchs to study their migration along the South Carolina coast.

Videos by: Rachel Strieber

“I tag year round… I’m really crazy,” said McCord.

McCord has been fascinated by butterflies since he was a child and started researching monarchs full time in 1996. He earned undergraduate and master’s degrees in wildlife and fisheries biology.

The monarch is one of the most recognizable butterfly species in North America, according to the National Wildlife Federation. They are famous for their brightly-colored, orange wings and migration south every fall.

McCord said you can find him by looking for the dirtiest white Honda Pilot on the roads in Folly Beach.

“There hasn’t been another human in my car in over a year,” said McCord. “It’s just used to catch butterflies.”

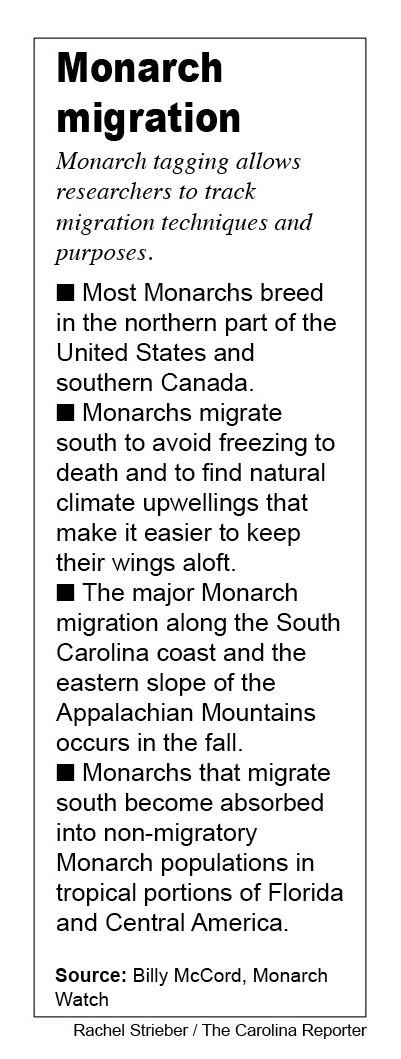

McCord reports all his tagging information to Monarch Watch, a nonprofit volunteer-based citizen science organization, which tracks monarch migration around the country.

Volunteers at Monarch Watch collect the tagging information from researchers like McCord to share with scientists to develop tagging techniques.

McCord is the most knowledgeable about monarch movement in and out of South Carolina, said Angie Babbit, volunteer communications director for Monarch Watch.

“He’s been keeping an eye on that for quite a long time,” said Babbit. “We send him a lot of tags, and he knows a lot about monarchs in South Carolina.”

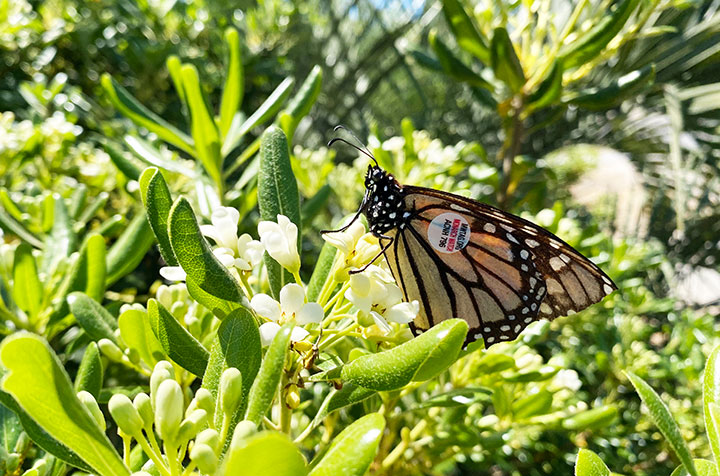

Tagging is essential for tracking monarch migration. A tag is a small paper sticker placed on the underside of a butterfly’s wings with tracking and contact information for the organization that produced the tag.

“Tags that came from Monarch Watch are designed specifically for marking monarch butterflies,” said McCord. “If somebody were to find one of these monarchs… they will notify Monarch Watch, and Monarch Watch contacts me.”

“That’s why I find it important to catch them. If I don’t catch them, I can’t put tags on them. If I can’t put tags on them, I can’t tell anything about them even if I do catch them,” said McCord.

McCord spends his days driving along the James Island and Folly Beach areas. When he spies a monarch, he pulls his car to the side of the road and quickly grabs his net. The process is difficult and time consuming.

“To catch them, you’ve got to be super quick, so I’ll stomp my front foot, because it helps you speed up your swing, just like karate,” said McCord.

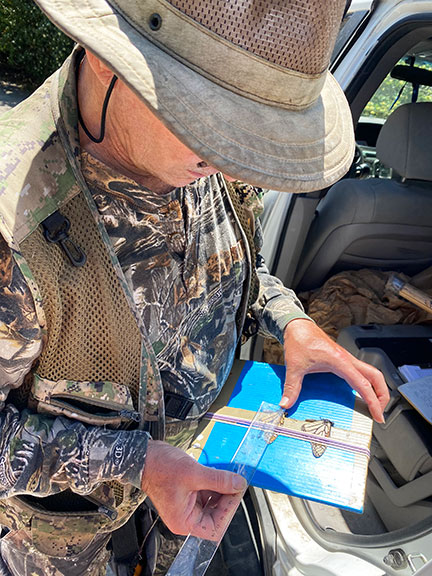

McCord invented a tagging platform and technique, which he uses after catching a monarch with his net.

“I created [the platform] out of some corrugated plastic, because the thickness of this plastic is almost identical to the width of the monarch’s body,” said McCord. “So, what I do is I take him, put him in this envelope when I caught him to protect him, and then evaluate his wings.”

After tagging a monarch, McCord records detailed notes about where it was caught, gender, temperature, time of capture, wing length, and condition of the wings. Gender is determined by observing the wings. Male monarchs have two black spots on the center of their wings, which females lack, according to the National Wildlife Federation.

McCord then sets the monarch free at the same site where he caught it.

“That tag will stay on that butterfly for its life and beyond,” said McCord.

Sometimes, McCord will catch 20 or more monarchs in one swing of his net. He developed a unique tactic for handling many monarchs at once.

“One day, out of frustration [trying to tag many monarchs in one net swing], I took one and stuck it in my mouth, and it played dead,” said McCord.

This is now a routine strategy for McCord. He does not bite the monarch, but holds it in between his lips. If he were to bite one, it would kill the butterfly and himself, because monarchs are poisonous to humans if eaten.

“I have never killed a butterfly,” said McCord.

While his passion is for chasing butterflies along the South Carolina coast, McCord also tracks other plant and animal life, one species of which he holds a unique Guinness World Record.

“I have consecutively put and spit out of my mouth 16 carpenter bees, and they all flew away. I hold the Guinness World Record for that,” said McCord.

McCord said there is a common misconception that millions of monarchs migrate to South Carolina around this time every spring.

“The major migration is in the fall. What everybody is taught is that the monarchs all go to Mexico in the fall, but we know from tagging… things that my tagging has shown… that monarchs that migrate along the coast – hardly any of them go to Mexico,” said McCord. “Instead, they continue to go south and end up in south Florida, and some of them even go to Cuba… where they become absolved into non-migratory monarch populations.”

Many monarchs spend the winter along the South Carolina coast.

“I was the first one to ever document that there are monarchs wintering along the South Carolina coast. The climatic conditions [in the Folly Beach area] are almost identical to what the monarchs are seeking,” said McCord. “They are looking for a place where the mean nighttime temperature is around 40 degrees and the mean daytime high is around mid to low 50s, and the humidity, which keeps them from defecating.”

McCord recently found a monarch that he had tagged 126 days prior in November, so he knows now it was a winter resident of the South Carolina coast.

It’s not just adult monarchs that McCord catches. He collects butterfly eggs and caterpillars in the swamps along the South Carolina coast.

“I collected over 200 [monarch] eggs. Caterpillars eat milkweed. There’s a native milkweed that grows in those swamps that I picked… I take it home and feed it to the caterpillars,” said McCord.

McCord has over 400 caterpillars in his house currently and has caught hundreds of thousands of butterflies in his lifetime – sometimes, more than 200 in one day.

“If there was a Guinness World Record for the most monarchs tagged, I would almost certainly have it, but I don’t really care for that kind of recognition,” said McCord.

Once McCord catches a butterfly, he assesses its gender, approximate age and conditions of its wings.

McCord carefully records details about the monarchs immediately after capture for tracking purposes. He then evaluates the monarchs’ wings on the tagging platform he invented out of corrugated plastic. The thickness of the plastic platform is almost identical to the width of the Monarch’s body.

Tags that came from Monarch Watch are designed specifically for marking Monarch butterflies. Once tagged, McCord releases the monarchs exactly where he caught them.

McCord sends his research and data to Monarch Watch, a nonprofit volunteer-based citizen science organization, which collects tagging information to track monarch migration around the country.

McCord’s Honda Pilot is filled to the brim with monarch chasing and research materials. He has not had another human in his car in over a year and also uses it to store monarchs, caterpillars and chrysalides.

McCord also collects eggs, chrysalides and caterpillars in the swamps of the South Carolina coast. He has over 400 caterpillars in his house currently and has caught hundreds of thousands of butterflies in his lifetime.