SOURCE: Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention and Advancement/Madelyn Weston/Carolina News and Reporter

Improved administrative support could reverse a spate of teacher vacancies, but some parents and education experts say school leaders’ approaches are adding fuel to the fire.

“The districts with the least turnover, they have consistent leadership at the top,” said Sherry East, president of The South Carolina Education Association. Those district leaders “get to know their community and their district.”

Some say it will take strong leadership to handle what’s pushing teachers out of the classroom.

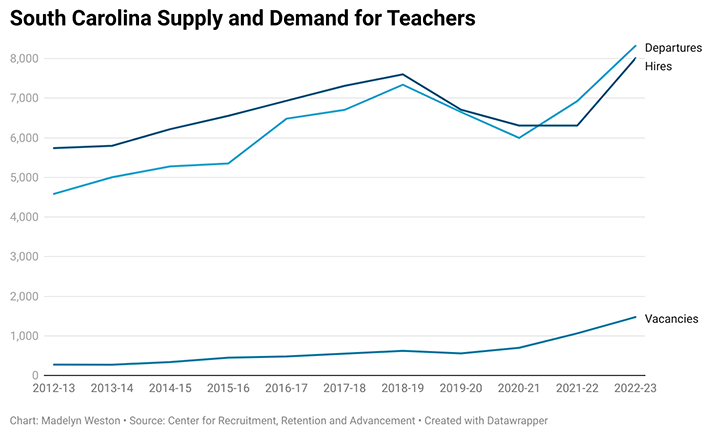

Teacher shortages long have been a problem across South Carolina, but they’ve been getting worse. Vacancies statewide jumped to 1,474 last school year, up 39% compared with the year prior, according to a report by the Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention and Advancement.

The remaining teachers work longer hours and pick up new responsibilities while districts scramble for solutions.

Student behavior has worsened, with a lack of follow-through from school leaders, educators say. And teachers covering for each other’s classes lose planning time, which increases their workload.

“It ends up leading to burnout,” said Patrick Kelly, the director of government affairs at the Palmetto State Teachers Association.

Sudden teacher reassignments mid-year

The latest administrative controversy comes out of Richland County School District One.

The controversy centers on mid-year teacher transfers to different district schools to address disparities in class size.

Richland One reassigned 11 elementary school teachers mid-October. The sudden transfers were front and center in public comments during a packed Oct. 24 school board meeting.

Some parents said their children were confused and heartbroken at unexpectedly having to tell their teachers goodbye. Some educators also said teachers couldn’t possibly have enough time to prepare for a new grade level or curriculum in just a few days.

Richland One parent Emily Luther spoke, calling the meeting a “post-facto justification.”

“What happened this past week was poorly executed at best but is probably more accurately described as unconscionable,” said Luther, whose kindergartner lost his teacher.

One teacher was expected to move within two school days, without compensation or assistance, said Sherry East, president of The South Carolina Education Association teacher organization. East said in an interview that the right thing to do would have been to give teachers at least a week to move.

Beth Moore, another parent of a kindergartner whose teacher was reassigned, told trustees she felt blindsided by Richland One’s news.

“I’m disturbed by the complete disregard for the well-being of the students affected, the cavalier assumption that children will easily adapt,” Moore said. “The administration has failed those children for whom stability is the most important thing.”

There could have been more communication and respect, Moore said.

Teachers are reassigned to maintain class sizes once enrollment settles down.

Student enrollment is finalized on the 45th day of school, school district spokeswoman Ilyssa Weiner told the Carolina News and Reporter in an email that provided only general information. She declined requests for an interview before the meeting, saying questions would be answered then.

“Staff reassignments are not uncommon,” Weiner said.

But parents and some board members said the district knew it had an unusually large number of vacancies and didn’t do enough about it before the school year started.

“Richland One is gaslighting the entire state by saying that what they’re doing is not uncommon,” Kelly said.

Kelly said there was disorganization and confusion among teachers, including one teacher who was told she had been transferred to another school. But as of late-afternoon the day before she was set to teach at a new school, Kelly said, she still didn’t know what grade level she’d be teaching.

“This is devastating for the students and the teachers involved,” Kelly said. “For the teachers involved, the stress that it’s causing them is borderline inhumane.”

Elementary students thrive on routine and relationships, so teacher reassignments damage the comfortable classroom environment, he said.

“You just ripped that person out of that child’s life,” Kelly said.

Richland One has been hit particularly hard by vacancies, with 150, said district trustee Robert Lominack, who criticized the way administrators handled the transfers to address the problem.

Statewide early career teacher departures continually increase

Teacher departures have been on the rise statewide for at least 10 years and have gotten worse in the past few years.

There were 8,321 S.C. teacher departures in the 2022-23 school year, including those who went to another district, according to most recent state data. That number is 20% higher than a year earlier.

A key issue, teacher pay, has been lagging behind the national average for a long time.

The nation’s average base salary for teachers in 2021-22 was $66,397, based on a report by the National Education Association. The South Carolina average was $54,814, the State Department of Education reported.

Gov. Henry McMaster wants to raise the starting pay for teachers to $50,000 by 2026.

Many school districts offer bonuses for new hires, but Kelly said the incentives are a band-aid because they are temporary.

Teachers early in their careers were disproportionately represented in the state’s most-recent data on departures: 3,015 of the teachers had less than five years of experience, up 26% from the year prior.

Most of the teachers reassigned at Richland One are in their first year.

Reassignments are based on the most recently hired teacher by grade level, said Kalu Kalu, Richland One’s director of certified employment services. The district did not ask for volunteers to move, Kalu said.

In Richland One, trustee Barbara Weston raised questions during the Oct. 24 meeting about work culture in the district.

“People come and they say to you, ‘You are not dealing with me in a humane manner,’” Weston said. “‘You are taking us like we are cattle or sheep and herding us one place or the other. Hear our voice.’”

Richland One has a mentorship program for teachers, which Kalu said should be available to those reassigned. Richland One is also looking into providing the $250 classroom funding for the new assignments, typically given at the beginning of the school year, Superintendent Craig Witherspoon said.

Many school districts have programs designed to support teachers and hopefully keep them. Fairfield County, for example, has a mentorship program for first-year teachers.

“They feel a sense of isolation,” said Superintendent J.R. Green of Fairfield County Schools. “The more that we do to support them, the more likely we are to keep them.”

How Midlands schools are handling vacancies

Teachers across the state told the Carolina News and Reporter they are having to cover for others’ classes during a planning period, leaving them with less planning time of their own.

Lexington-Richland School District Five proposed a waiver on Sept. 7 to the State Board of Education to allow teachers in critical needs areas to teach over 25 hours a week.

The waiver would allow teachers of small programs to cover one additional class, said Peter Lauzon, president of the Lex-Rich Five branch of the S.C. Education Association.

“There’s been a lot of turnover because of COVID, and the people that were eligible for retirement definitely retired,” Lauzon said.

Schools in the Midlands also have brought in substitutes for long periods to fill the teacher shortages.

Special needs education has its own challenges because teachers require a specific certification.

Finding special education teachers to teach students with autism, especially, has become more difficult in Lexington County School District Two.

“We’ve implemented every initiative that we know to implement, and we still have these vacancies that we … are really struggling to fill,” said Angela Cooper, Lexington Two’s chief human resources officer.

Having a day off doesn’t always mean having a day off.

Gov. Henry McMaster signed a bill into law in May to give full-time state employees such as public school teachers six weeks of paid parental leave. The bill covers the birth of a child, placement of a foster child or adoption of a child.

Some teachers who might have otherwise left education stayed because of the bill, Kelly said.

But only certified teachers can grade assignments, so some teachers on leave continue to work from home, East said.

“When a teacher is home sick or on maternity leave, oftentimes they are still working, either grading the papers, communicating with parents, giving the lesson plans,” East said.

The Palmetto teachers association reports that 80% of its members work more than 40 hours per week, and 52% work more than 50 hours.

Class sizes also have increased because of teacher vacancies, meaning more grading and less individualized instruction, Kelly said, which causes a ripple effect.

“One of the No. 1 things that causes students to act out in class is when they don’t understand the material because they’re not engaged academically,” said Kelly, who has taught for 20 years.

And students who threatened teachers and even attacked a teacher were returned to the classroom a few days after several recent incidents, educators say.

Teachers too often don’t feel supported, Kelly said.

“Teachers aren’t leaving the profession so much as they are leaving leadership,” he said. “South Carolina’s got to find a way to reverse this educator shortage.”

Teacher departures have surpassed the number of hires, bringing vacancies to 1,474 in South Carolina.

Richland County School District One trustee Robert Lominack asks a human resources official how a large number of vacancies at one elementary school were handled. (Video by Josie Frost/Carolina News)

Patrick Kelly, of the Palmetto State Teachers Association, proposes policies to state legislators to improve education for students and support for teachers. (Photo by Madelyn Weston/Carolina News and Reporter)

Sherry East, president of the South Carolina Education Association (Photo by Madelyn Weston/Carolina News and Reporter)